Malaya – Java – Sumatra 1945 – 1947

Ops in Indonesia Flying Operations Move to Java and Sumatra Maj. "Warby" WarburtonLanding on Malayan Peninsula – Op Zipper”

The Squadron set out with the aircraft being loaded onto the Escort Carriers HMS Smiter and HMS Trumpeter, the ground party sailing in LSTs, (Landing Ships Tank) with fully waterproofed vehicles. Gunner Ray Pett wrote of his experiences at this time,

‘Having driven to Bombay to get vehicles waterproofed, we then returned to Madras, where Captain Bromwich, Gunner Vin Weaver and I embarked on one of three LCTs, with a mixture of Gurkhas, Infantry and a few vehicles including our 15 cwt. We were informed we would be landing two or three days before the main landing: we were going ashore just below Port Dickson as a decoy for main landing. After a few days at sea we were told the war was over but we were to continue.

were just the three LCTs [Landing Crafts, Tank] – no convoy: one of the LCTs had no bow door but not ours, thankfully.

three boats beached, I think early morning, and we came ashore in assault craft with the Gurkhas. The landing took all day as the first truck slid sideways blocking the ramp and on the second LCT they had great difficulty in releasing the ramp. Eventually we managed to regroup and entered Port Dickson with the Gurkhas, etc.

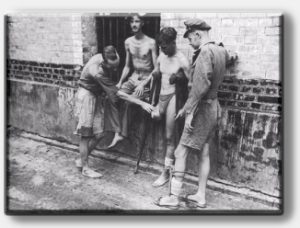

The Japanese had not been disarmed as we were the first troops in. We were told of a POW camp outside Port Dickson and took some Gurkhas with us to the camp to find fully armed Japs were on guard at the main gate, much to the annoyance of the Gurkhas. It was mostly Indian and Chinese civilian and military, the sight and smells were horrific.’

It was fortunate that Zipper was not opposed by defenders on the shore, as the beaches had been inadequately surveyed and many of the heavily laden landing craft ran aground on sandbanks and would therefore have been sitting ducks for enemy fire. On 09 September, Squadron personnel landed on the beach at Morib (near Port Dickson) – possibly the first airmen ashore in Malaya. A Flight, with 37 Brigade, landed at Sepang and the OC and C Flight landed in the Morib area. The following day two aircraft arrived, having taken off from HMS Trumpeter. A Flight was established at Port Dickson. As had been the case at Rangoon, radio communication between the ground party and the aircraft failed, but once again the aircraft landed safely.

Some of the Squadron ground personnel travel to Malaya in Sept 1945 in a LST as part of the Morib Landings

Indonesian Operations

On 11 September, a day ahead of the rest of the Army, Denis Coyle and Jimmy Jarrett flew to Kuala Lumpur in Auster V TJ215, to be waved in and parked by the ‘Nip duty crew’, who tried to surrender to them, which they found somewhat embarrassing.

Japanese troops surrender to the Squadron in Kuala Lumpur, September 1945

They flew in the Victory Parade on 14 September, which was an honour, but no less than the Squadron deserved. Denis Coyle did not think much of the main airfield which he felt sure was going to be rather crowded, but found a very fine strip on the golf course which ‘the Japanese had kindly constructed but never used’ which was where the remaining eight Austers from HMS Trumpeter landed on 24 September. In the somewhat ironic words of Denis Coyle,

‘Having established a main base the flights proceeded to get as far away from Squadron Headquarters as possible, C Flight going to lpoh where they were based on the race course, A Flight to Johore Bahru, where they also were on the racecourse, while B Flight, having been retained at Kuala Lumpur until October, found a very comfortable billet on the golf course at Trenganu on the east coast.’

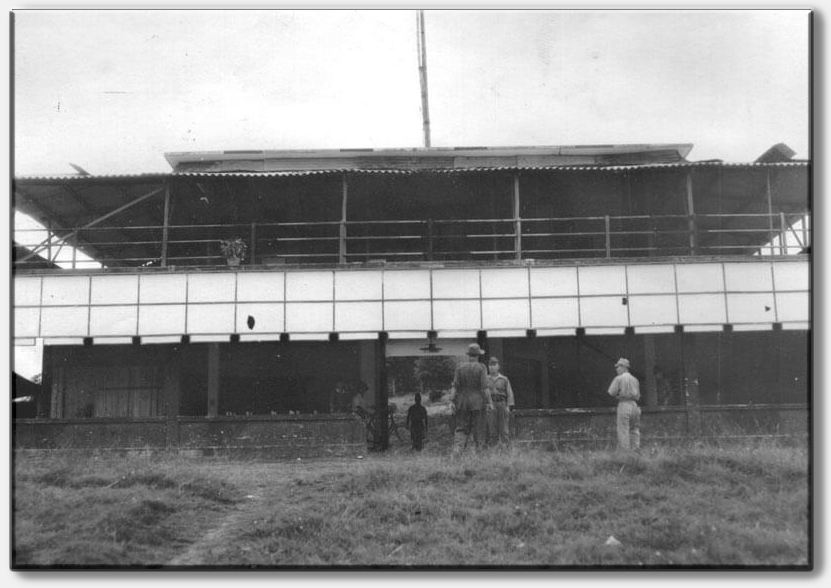

The Squadron’s base on Kuala Lumpur golf course

Frank McMath, who would assume command from Denis Coyle on 10 November, added,

‘In spite of the disappointment over missing our first large scale combined operation, the month proved to be one of the most interesting in squadron history. As soon as the landing shambles had been straightened out and all Flight and Squadron Advance Parties were complete, the organization of a Tactical SHQ and independent and detached flights proved capable of working extremely smoothly. Throughout the Squadron morale was very high, due to the pressure of work and also to the unexpectedly pleasant climate and country. All ranks were unanimous in wishing that the Burma campaign could have been fought in Malaya.’

“Flying Operations”

The duties that fell to the Squadron during this period – covering the whole of Malaya – included flying passengers and mail, as well as reconnaissance sorties for bandits, photographic work, ‘roads, railways, sea lanes, estuaries, rivers, mines, factories, plantations etc.’

They also assessed the work required by the British Military Administration (BMA) – which was an interim body established by Proclamation No. 1 (September 1945), of Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, the Supreme Allied Commander of South-East Asia Command, giving it, ‘judicial, legislative, executive and administrative powers and responsibilities and conclusive jurisdiction over all persons and property throughout such areas of Malaya.’

The Federated Malay States, the Unfederated Malay States, as well as the Straits Settlement, including Singapore, were placed under temporary British military rule. Despite the vast responsibility give to the BMA, the time was described in the C Flight diary as ‘a fairly gentle existence.’ Such was its reputation for quiet efficiency and a ‘can do’ attitude. This pleasant interlude was not to last, as in November A Flight was given twenty-four hours’ notice to prepare for operational deployment to Java in the Dutch East Indies. The Japanese surrender had left behind a power vacuum which the Dutch authorities, weakened by five years of occupation at home and abroad, were contesting with the Indonesian Nationalist movement.

The country was in a state of chaos, with little viable transportation and severe food shortages. It had a population of an estimated 50 million in an area about the same size as England and was probably the most highly cultivated and productive area of its size in the world; more than a quarter of its surface being given over to rice growing alone. The Republic of Indonesia had been proclaimed on 17 August 1945 by Dr Achmed Sukarno and was the prelude to ‘an unpleasant little war’ which was to last for five years and cost thousands of lives, until the Dutch somewhat reluctantly conceded to Indonesian independence in December 1949.

In the autumn of 1945 the British and Indian Armies were therefore obliged to send forces to ‘maintain law and order and save human life’ – not least the lives of thousands of prisoners-of-war and internees, who were in urgent need of rescue and repatriation. A booklet was issued by SEAC giving helpful information and advice, including the following,

‘Much of the success, or otherwise, of our occupation of the Indies, rests on the impression you succeed in making on the native. There are between 40,000,000 and 50,000,000 in Java alone and that’s not a number to be regarded lightly. You’re in his country. He knows all about it. Don’t be too proud to learn from him. Make a friend of him. You will find it well worth the trouble.’

Allied Forces Netherlands East Indies (AFNEI) was assembled under the command of Lieutenant General Sir Philip Christison and sent with all haste, the 23rd Division to Java and a Brigade Group of 26th Division to Sumatra. Shortly before A Flight arrived a major battle had taken place at Surabaya, a major port and naval base in East Java, on 10 November, in which at least 6000 Indonesians died and perhaps 200,000 fled the devastated city. British and Indian casualties totalled approximately 600. It is therefore understandable why A Flight set sail ‘with mixed feelings’ from Singapore for Java on 20 November.

The Flight was travelling by LST at assault scale – four aircraft, six vehicles, five officers and seventeen other ranks. The men were nearly all founder members of the Flight, but only two of the officers had been with the Flight more than a week. Its role would be to undertake Air OP duties in the Surabaya area in support of the forces on the ground. They soon had a foretaste of what conditions were to be like, as the local Indonesians had several field guns covering the town and throughout the night of A Flight’s arrival they harassed the dock area at irregular intervals. On the morning of 24 November, the Flight disembarked and the aircraft were towed up to the airfield behind Jeeps.

As soon as the aircraft had been assembled flying started in support of operations to clear the rest of the town. Neither of the two Field Regiments (3rd and 5th Indian) had much experience of AOP, and, indeed, for the first fortnight the biggest task was to find some work. Life was at first far from comfortable, water was rationed to one gallon per man per day and every night the airfield was harassed by the Indonesian artillery. In the air too, life had its dangers, as Captain R.T. Roberts found out on his second sortie, when he was engaged by a Bofors anti-aircraft gun. On 30 November, two shoots were observed for the Navy. HMS Cavendish, a War Emergency type destroyer, was due to celebrate her first birthday in the evening and as she had never fired a round in anger it was arranged that an Auster should go up and look for opportunity targets.

Early December was marked by a considerable increase of flying. Everyone was beginning to realize how much can be seen from the air. The town was cleared completely and company patrol bases established three to five miles outside the perimeter. The military situation remained the same from then onwards, with patrols daily sweeping the area about the town. Trevor-Jones became the first to have his aircraft damaged by enemy fire, when his sternpost was hit by a single shot. The new OC, Major Frank McMath, paid a visit and was even more unfortunate, being,

‘Fired on by an Indonesian when Jeeping from SHQ, the only British unit in the Batavia Red Light area, to the airfield. A burst of tommy gun was let loose at his feet and several pieces of metal lodged in both of his eyes. However in a trip in a Dakota with a Dutch stewardess he made vast improvements and he was able to fly to Kuala Lumpur as passenger.’

Move to Java and Sumatra

Meanwhile, back in Malaya SHQ, B and C Flights began making extensive reconnaissance and photographic sorties aimed at opening up the difficult terrain around the Siam border.

It was decided that in light of the prevailing circumstances, the rest of the Squadron would join A Flight in Java. On 11 January 1946, SHQ, with A Flight rear party and C Flight embarked on LSTs, while on the same day B Flight arrived at Singapore and awaited passage.

Early in 1946 C Flight went to Bandoeng in Western Java, which had a cool and pleasant climate.

The Squadron was at this stage equipped with a mix of Auster IVs and Vs, several of which were rather worn out. From its new HQ at Batavia, the capital, which had been founded by the Dutch in 1619, the flights were dispersed, C Flight went to Bandoeng, which was situated on a plateau about 2000 feet above sea level and so had cool and pleasant climate. When it arrived, B Flight was sent to Semarang, a pleasant residential town, which was some 300 miles to the east. Various types of sorties were flown – shoots, road convoy escort, casualty evacuation, photographic, mail and passenger flights. The C Flight diary muses on the rather anomalous situation in which they found themselves,

‘We did not have to provide our own guard as the airfield was splendidly guarded by our gallant collaborators the Japanese. This, however, was not without its drawbacks. Every now and then the Jap Liaison Officer would respectfully ask if we could spare the Nips employed in the Flight on cookhouse fatigues, dhobi etc., for a couple of hours, as they were required on arms drill.

However, since the Indonesians were scarcely of a friendly disposition and since the Japs periodically dispersed unpleasantly large numbers of armed belligerent youths in the unpleasantly near proximity of the Flight lines, we suffered these disruptions to our domestic economy.’

In April, Frank McMath spoke at some length on Radio Batavia, describing the Squadron’s activities in India, Burma, Malaya and the NEI. From May, B Flight ceased to function as an operational Flight and was renamed B (Holding) Flight, to be attached to SHQ as a training flight for new intakes, while C Flight arrived from Bandoeng to join SHQ in Batavia.

Towards the end of the month A Flight, commanded by Captain Russell Matthews MC, moved 1000 miles by LST from Java to Medan on the island of Sumatra to support 26th Indian Division. He was accompanied by Jock, his white English Bull Terrier, who enjoyed flying but absolutely hated cats and was not very friendly towards the Japanese, Indonesians or his master’s lady friends.

The area abounded in tobacco plantations, as pre-war Medan had been famed for the quality of its cigars. One section was based at Padang on the Indian Ocean coast, with the rest of the Flight on the Strait of Malacca coast between Sumatra and Malaya. It is interesting to note that one of the first occasions on which the Squadron’s flight safety radio net was actually used for rescue purposes, was when a lone LCT, carrying Flight trans port from Java to Sumatra broke down, with the result that the vessel was drifting out of control off the normal shipping routes and with a non-functioning naval wireless. Communications were established between Flight personnel and SHQ on its Army radio, SHQ telephoned the RN and a rescue was set in motion.

Return to Top

Era of Major “Warby” Warburton

On 10 June, due to the effects of his wounds, Frank McMath handed over command to Major H.B. ‘Warby’ Warburton, who later had much to say about the Squadron’s involvement in this conflict,

‘The scale of operations in the Netherlands East Indies after the ceasefire in the Far East was deliberately played down for political reasons. Operations were being continued, not against pockets of isolated Japanese resistance in Java and Sumatra, but against a well-equipped and well-organized Communist directed terrorist organization. Their aim was simply to unbridle Indonesia from the Dutch yoke, and they used the short period, between the war ending and the occupying forces arriving, to help themselves to vast dumps of military equipment, and to start organized training on a strict military basis.

I took over at the end of May with hostilities in full swing. I had left the Squadron in Malaya less than a year before, and in this time there had been almost a complete change of pilots. Morale in the Squadron was high, and a swashbuckling atmosphere prevailed amongst the pilots, who were allowed their head to great advantage. The aircraft, however, were rapidly becoming tired, having withstood the harsh weather and heavy utilization of the Burma campaign.

Most of the airframes needed recovering, the fabric having rotted and become brittle; after stripping off the fabric, several aircraft had to be written off as it was found that the airframes had not been sufficiently protectively treated and had corroded to a dangerous degree. Some newly-coated reserve aircraft were called forward, but the inspection of these became critical when it was discovered that one aircraft had a large and unexplained hole in the fabric; when this was stripped back, a large chunk was found to missing from the main spar – a hungry rat had made its nest in the wing, chewing its way, bit by bit, into the main spar, putting it beyond repair.

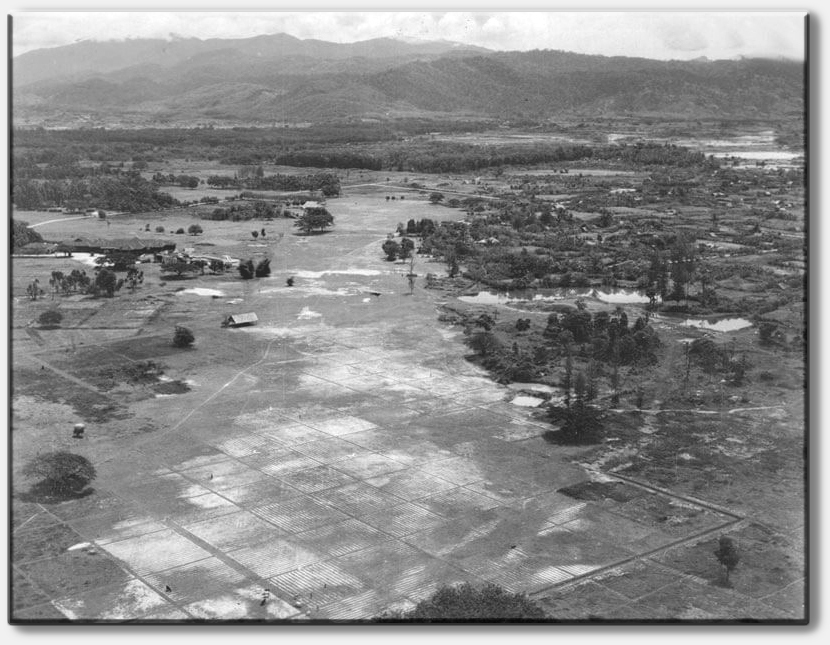

Our main tasks were: Air OP; Visual Recce; Photo Recce and Casualty Evacuation. The RAF was not able to finish PR cover of strategic targets, owing to lack of spares for PR Spitfires. The Squadron took over the completion of 4500 pinpoint obliques, along a coastline of 900 miles, within a target time of three months and before the monsoon broke. Some of these pinpoints involved a round flight of 450 miles and five hours duration; this was achieved by the Squadron Engineer Officer fitting a second tank behind the pilot with a manual rotary pump in between the seats to effect the fuel transfer; this arrangement gave the aircraft a safe five hours endurance with a bit to spare. Captains Tommy Tommis and Mike Cubbage were the two officers who took on this task, much to the amazement of Air Force HQ, as the task was given to us rather tongue in cheek. Given also the fact that the Photo Section consisted of one LAC photographer and one gunner amateur enthusiast, the processing of some 13,000 prints in total was a remarkable feat.

As our operations progressed, we found that the terrorists were becoming an increasing menace in taking pot shots at us: they were effective and all our aircraft were hit from time to time. Things came to a head when one of our aircraft, flying out of Medan, took a 0.5-inch cannon shell through the main spar; we now decided to take our own countermeasures. Pilots had their own choice of weapons – some chose the Sten Gun, others preferred the Bren Gun, fired through the camera port; one pilot, Dickie Parker, always used a long-barrelled Mauser pistol, with which he was a good shot! It was not long before the opposition were treating our Austers with more respect.

One very dramatic success was scored by one of our RAF corporal cooks who was acting as observer to Captain Ken Litt. An Indonesian staff car, resplendent with flag, was engaged; the car ran off the road, hitting a tree, the radiator blowing up in a spectacular cloud of steam. This little action had an immediate effect on the occupants of the cookhouse, the food being better than ever and from then on we had a constant flow of volunteers from the erks to ride as observer.

One Auster we fitted with a light-series bomb rack and only the lack of 20lb GP fragmentation bombs prevented the “Auster Cloth Bomber Mk IV” from going into action before we left Java.

An unusual but pleasant feature of operations in Java was the existence of an unofficial truce, which was observed on Sundays at nightfall or during heavy rain; this at least allowed us to relax and enjoy the lavish entertainment which was offered by the various Service Messes and Embassies; when this palled we could always enjoy the piano playing in our own Mess by Mike Cubbage or Bill Eastman.

The Dutch were most generous and living conditions were considerably eased by the gift of several refrigerators and electric fans; our Mess was comfortable and the food was cooked by an excellent Chinese cook. One asset was a permanent tailoress who was employed doing repairs and making excellent sports jackets out of lightweight blankets. Two Japanese infantry subalterns kept the garden tidy and the drains clear, and there was an ample number of Javanese batwomen to look after us. The Squadron Mess, which was situated in one of the more doubtful areas of Batavia, was prone to raids by the light-fingered gentry, who completely cleared the Mess of all eating irons, pots and pans three times, in spite of the fact that the Mess was wired in by triple Dannert wire, and booby-trapped each evening with trip wires and grenades – it was distinctly dangerous to venture out to obey the calls of nature after bedtime, as the slightest movement in the garden would bring forth a fusillade of Sten Gun bullets from the bedroom windows.’

‘Warby’ would become a legendary name in Army aviation circles – he completed operational AOP tours during the Second World War in North Africa, Italy, north-east Europe and the Far East, before returning to England at Andover and then being summoned to Java.

Stories concerning Warby are legion. In Indonesia, he was known to raise morale by declaring a weekly ‘Swiss Navy’ day, when officers were obliged to wear their headgear back to front and on returning from the local fleshpots, to drive their Jeeps in reverse. In Malaya, where 656 was at one time sharing an airfield with a Spitfire squadron, he was somewhat annoyed by the bragging of a young fighter pilot who claimed that soldiers flying Austers would not stand a chance against a well handled fighter. Warby challenged the young man to a ‘duel’ and in a ‘dazzling display of evasive flying’ made a complete fool of him in front of an appreciative crowd of spectators on the ground. That night he ostentatiously wore spectacles and fumbled his way to the bar where drinks were on the RAF.

While in Indonesia, Warby also wrote a letter to Squadron Leader P. Gordon-Hall, the Chief Flying Instructor at 43 OTU RAF Andover, with details of some lessons learned,

‘We are carrying out a lot of shooting and the country is much easier to map-spot than Salisbury Plain. We usually fly at 1500-2000 feet, at which observation is perfect and we either fly behind or above the target. We don’t fly lower, as the Extremists are good rifle shots and also have LMGs. On the other hand, somebody dumped our armour plating in the sea before our entry into Malaya. There is not enough emphasis on photography in the present OTU programme – at present photography is a very close second to our primary task of Gunnery.

Pupils must be taught to fly absolutely accurately over long distances at heights from 50 to 5000 feet and I can say from experience that a sortie of an hour and a half at 50 feet does take a hell of a lot of concentration. Our longest projected photographic sortie up to date is 270 miles, 250 miles of this over occupied country; this necessitates a long-range tank, as our aircraft only do 80 mph IAS. (The long-range tank is our own modification, of which we will send you photographs; it is 100 per cent better than the official Taylorcraft mod). We still have a few tricky ALGs to deal with – the pathetic take-off performance of our ancient aircraft making things dicey at times. The standard of flying is quite satisfactory, but airmanship generally bad.

In conclusion I should like to add that we have flown 110 operational sorties in the first ten days of this month and considering we only have eleven old aircraft, nine serviceable at the moment and nine pilots below establishment, you can guess we are all very busy.’

There were also some exciting moments for A Flight in Sumatra,

‘Life on the ground at this time became considerably more dangerous than life in the air. Double guards on the billets were essential as there were no troops between them and the Indonesians. One night, Gunner Jimmy Wyatt, made his first attempt at winning a VC: in the early hours he observed two characters creeping inside our defended locality. He challenged and then fired five rounds at the offenders; to conserve ammunition he fixed his bayonet and charged three others who were hiding in the bushes. No hits were observed, but later in the morning two Indonesian ambulances visited the adjacent kampong.’

Auster IV flying over the jungle in Java

C Flight transferred from Java in September, reinforcing the A Flight detachment at Padang. In October, an Auster Float Plane trial was carried out at RAF Seletar by Squadron Leader A.M. Rushton, DFC, 209 Squadron RAF [which was equipped with Short Sunderland Mk V flying boats] and Major Warburton. After one flight and one take-off aborted following a loud bang from an undercarriage strut breaking, the trial was called off on the reasonable grounds that the aircraft was underpowered, the floats were not adequate and the undercarriage not strong enough.

A and C Flights were recalled from Sumatra in November, with the last operational task being carried out by C Flight on 26th and they were pleased to receive a valedictory letter from Major General R.C.O. Hedley, DSO, Commander, Allied Land Forces, (Sumatra),

‘Before you leave Medan and Padang, I want you to know how much I appreciate all the splendid work which you have done for 26th Indian Division. You have earned the gratitude of all our fighting troops for your willing, cheerful and efficient cooperation, which has so materially assisted them to carry out their tasks. Thank you all very much. Goodbye and good luck.’

The Pilots of 656 Squadron under the command of the redoubtable ‘Warby’ at Kuala Lumpur in December 1946

Then on 28 November 1946, the Squadron handed over its commitments to 17 (Dutch) Air OP Squadron and began to move back to Malaya, but not before the a very appreciative letter was received, from the AOC, Air Commodore C.A. Stevens, CBE, MC,

‘My Dear Warburton, It is with very great regret that I write to say goodbye to No 656 Squadron, who, starting with the arrival of A Flight in Surabaya at the end of November 1945, have been under my Command in NEI for almost a year. You have been fortunate in being selected as the one Air OP Squadron to continue on active operations for a full year and more after the defeat of Japan. Your work here has been difficult and often dangerous, but you have completed all you have been called upon to do with skill, initiative and enthusiasm.

From the troops on the ground, with whom you operate in such close contact, I have heard nothing but praise. I would like also to mention your invaluable photographic reconnaissance work and the exceptionally long-range flights you have undertaken in this connection.

I would like to thank you personally and all past and present members of No 656 Squadron for the truly excellent job you have done in the NEI and I hope you will enjoy life at your new home at Kuala Lumpur when you foregather there next month. Good-bye and good luck to you all wherever you may go.’