Malaya – Brunei – Borneo 1961-1969

Move to KluangBruneiConfrontationLong Pa Sia1965During 1961 there were many changes in the Malaya Theatre. 28 Commonwealth Infantry Brigade Group, ‘re-roled’, reducing time for conventional Warfare and training to ‘Airportable Equipment Scales’, whilst fulfilling a strategic reserve role for the South-East Asia Treaty Organization.

This change of emphasis particularly involved 7 Reconnaissance Flight, which began to concern itself more with the air movement of its vehicles and stores, combined with the potential requirement, at short notice, to fly in support of 28 Commonwealth Brigade. Just prior to its departure from North Malaya it was involved in the first major airportable exercise – ‘Trinity Angel’.

From this point on, all light aircraft tasks in support of 2 Federal Infantry Brigade would be carried out by 2 Reconnaissance Flight, stationed at Ipoh. This Brigade was by then the only military force campaigning against the CTs ( Communist Terrorists ) in the border security area.

The Federation Police Field Force continued to mount operations against couriers and camps in North Malaya, and over the Thai border, in conjunction with the Thai Border Police. Visual and contact reconnaissance flights continued at a much slower pace than before, which was hardly surprising, as there were only an estimated 350 hardcore CTs left.

At Sembawang, 11 Flight supported 99 Gurkha Infantry Brigade Group on Singapore island, its main task being ‘Internal Security’. Based at Paroi Camp airstrip, Seremban, 14 Flight remained as 17 Gurkha Division’s Liaison Flight, and with 7 Flight commenced airportable training.

11 and 14 Flights each took delivery of three Beaver DHC-2s in September, whilst retaining three Auster Mk.9s as well.

The Beaver was a tough, high-wing, six seat, monoplane, with a capacity to carry half a ton of freight. It first flew in August 1947, with 1,631 eventually being sold worldwide, including forty-two to the British Army. It was a very reliable, robust aircraft, powered by a 450 hp Pratt and Whitney, engine, having an excellent short take-off capability, and was a joy to fly. Six pilots were converted initially, also the CO and 2i/c.

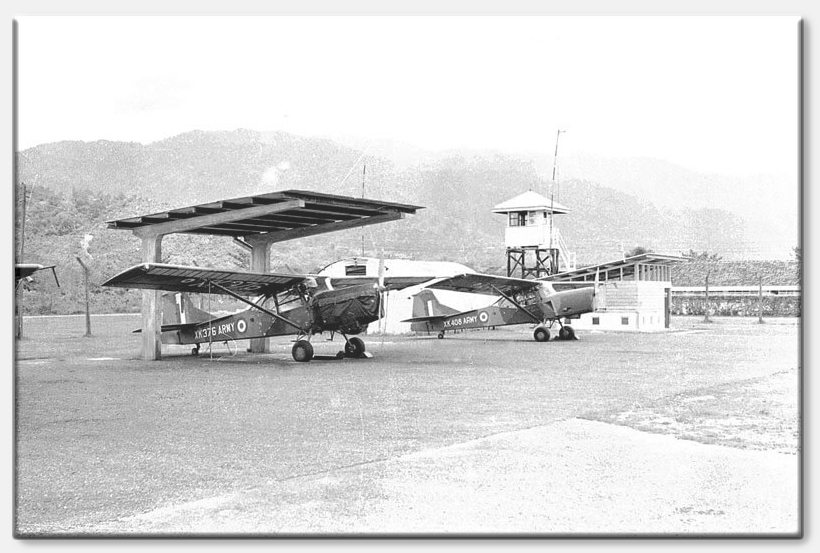

Two Auster 9’s at Taiping

16 Flight, which had been reformed earlier in the year to act as a Recce flight, for 48 Gurkha Brigade, was being run down prior to disbandment on 01 April 1962, and re-formation in Aden as one of the four Royal Armoured Corps’ manned reconnaissance flights. What remained of the Flight was placed with the Squadron HQ.

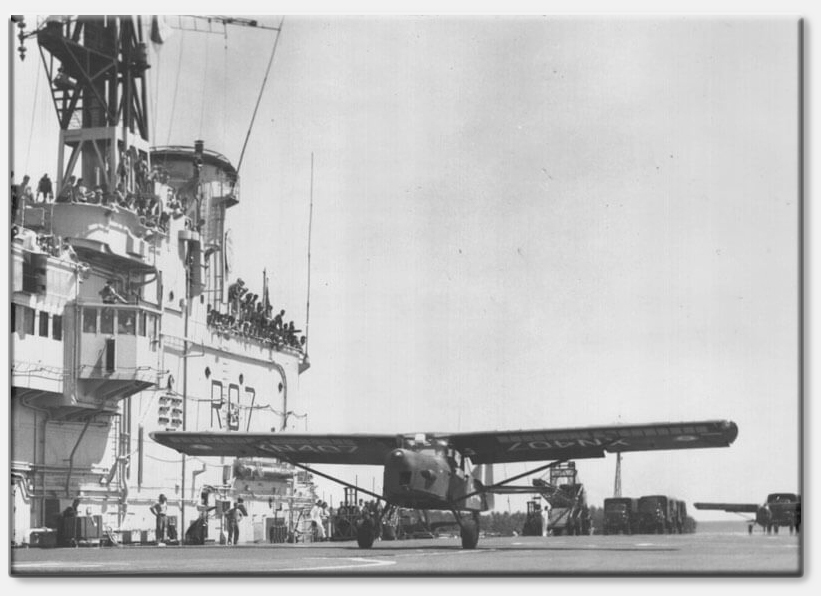

Squadron exercises were held on the East coast during the year, with successful deck landings being carried out on HMS Hermes and HMS Bulwark by 11 Flight, and several other pilots from SHQ and other flights.

In conjunction with 2 and 26 Regiments R.A., a number of pilots undertook successful shoots at Asahan Range’. 11 Liaison Flight also conducted many shoots with the Royal Navy. Other various tasks, described as ‘funnies’, included the night illumination by flares of a jungle helicopter LZ for a casualty evacuation by an RN helicopter, dropping mail to the C-in-C Far East Station at sea, and ‘flour bag’, bombing of a minesweeper flotilla, as well as numerous casualty evacuations.

An Auster taking off from the airstrip at the Asahan Ranges in Malaya in 1962

There was also another close encounter with a large yellow and black striped snake in the cockpit for Captain James Adair of 2 Flight, which hissed at him and slithered about as he banked his Auster, and eventually came to rest somewhere out of sight.

Three major search and rescue operations were carried out in quick succession in October and November. The first was for a Royal Malaysian Air Force Single Pioneer, which crashed in the Bentong Pass area, with the loss of all five on board. They were looking for a party of seventy schoolboys (and one schoolgirl) which were behind schedule on a jungle expedition.

The second incident involved a Canberra B.2 of 75 Squadron RNZAF, which took off on a night cross-country from Tengah to Butterworth in October, the period of the North East monsoons. Of the three aircraft taking part, the first turned back severely damaged by hail and lightning. The next went missing, and the third completed its flight. The missing aircraft flew into a cumulo-nimbus cloud at 40,000 feet, the pilot lost control and, after repeatedly telling his navigator to eject from what he believed to be an inverted spin, ejected himself at 8,000 feet. This was the third occasion on which this pilot had abandoned an aircraft. He walked out of the jungle after a series of lucky escapes. Two days later WO2 Standen of 11 Flight, and his observer, Corporal Goodey, found the wreckage. The navigator’s body was found with the aircraft when the jungle rescue team arrived.

The third and final search was for Captain Peter Hill of 2 Flight, who went missing while on a visual reconnaissance from Ipoh over South Thailand on 22 November 1961. His passenger in Auster AOP Mk. 9, XK374 was Captain O’Grady, of the Royal Army Dental Corps. In spite of an intensive air and ground search lasting seven weeks, no trace of the crew or aircraft was found, until 1967.

The air search was controlled by the RAAF at Butterworth, and, besides 656 Sqn. aircraft, included aircraft from the RAF, RMAF, RAAF and RNZAF. The ground search was carried out by units of the Federation Army and Federation Police, in conjunction with the Thai Frontier Police Force. Only the latter two forces were permitted to search in Thailand.

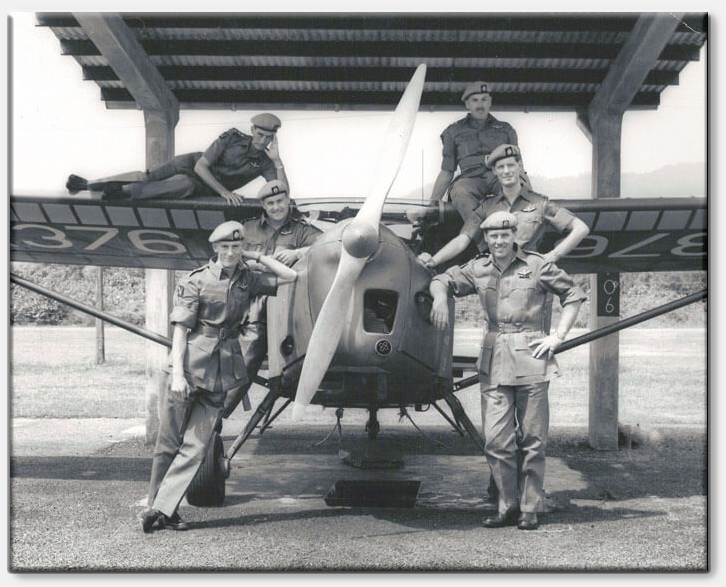

7 Flight pilots at Taiping in September 1961

During 1961 the Squadron flew 9,436 hours in Auster Mk. 9s, and 314 hours in Beaver A.L.1s,

It was also noted that two new pilots, Lieutenants R. Andrews, and C. Brown, of the New Zealand Army, joined the Squadron in December, for continuation and conversion training, before posting to 7 Flight early in 1962.

The major news for the first part of 1962 was very well described in the Squadron’s report for the ‘Army Air Corps Journal’,

“In the bad old days new arrivals to the Squadron were met by the Flight based in Singapore. They were introduced to the Navy at Sembawang, and gradually filtered to SHQ, thus ensuring that the newcomers were always well indoctrinated with the big city life before going ‘up country’. This happens no more, for this year was ‘movement year’, and there was no longer a ‘Singapore flight’.

To the consternation of all, the Squadron not only moved to Kluang, but remained there! Whether this was due to a high sense of Military discipline, or the advent of the Northeast Monsoons, is hard to say. Nightlife in Kluang certainly had nothing to do with it!

Kluang, for those who knew it, had not changed much. For those who have never been to Malaya, it is a small town in Johore, about 60 miles north of Singapore, and is distinguished in so much as the tourist has the choice of whether he comes to Kluang or not! The Squadron settled in, backed by that well-known, if slightly hackneyed phrase, a “Get-you-in Service.”

On the ‘Bricks and Works’ side, amongst other things, was the leaky hangar, and an almost completed new control tower! In fact, they were told that the tower was ‘the first permanent building to be erected in Kluang for many years’. The move was not without its humour, the Squadron, having been settled in Mala’, for many years in their old locations, endeavoured to bring their treasured belongings, which had reached fantastic proportions, with them. Someone even wanted to bring the pierced steel planking from Noble Field!”

Move to Kluang

The Squadron was busy even before the upheaval of the move to Kluang began, as it played a full part in Exercise Trumpeter, probably the biggest exercise ever held in Malaya. 7, 11 and 14 Flights all remained in being, 16 Flight returned from Aden, but 2 Flight was disbanded and the title taken up by an integrated flight in Northern Ireland.

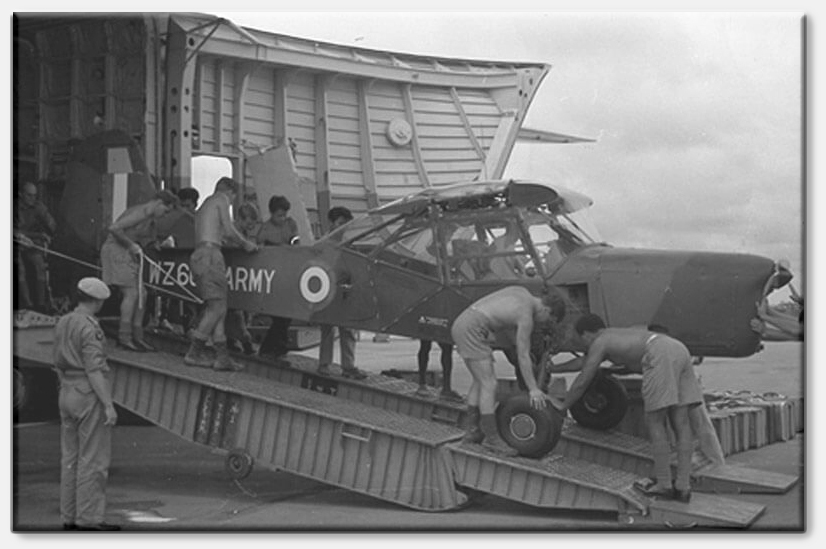

An Auster overhauled by Squadron Workshops in Kluang arriving at Kuching in an RAF Beverley

There was a considerable changeover in personnel, including the CO, John Cresswell, who had seen the Squadron through Emergency to conventional training, then to air portability, and from dispersal to concentration. He was succeeded by Lieutenant Colonel Bob Begbie, the first AAC officer to take command of the Squadron.

November saw the departure of the last three National Service Aircraft Technicians to serve with the Squadron (National Service wound down gradually from 1960. In November of that year the last men entered service, as call-ups formally ended on 31 December and the last National Servicemen left the Armed Forces in May 1963).

Return to Top

Brunei

The Sulu Sea pirates had become a dangerous menace to shipping, so between October and November 14 Flight deployed a Beaver in support of a joint Service anti-piracy operation on the north-east coast of Borneo, some 1,000 miles from Flight HQ. Captain W.P. Duthoit gave chase to the pirates, who, mounting twin outboard motors of considerable horsepower on their craft, could show a remarkably clean pair of heels when challenged.

This detachment proved invaluable, as it gave 14 Flight two months of excellent training over ground which was to prove more significant later. It also exercised the Squadron Workshops and Stores Section on maintenance over long distances, as in December the Brunei revolt broke out and events happened fast. The plan to incorporate British North Borneo and Singapore into a Greater Malaysia within the British Commonwealth had not gone down well in Indonesia, where President Sukarno had the ambition of dominating the whole of Borneo himself (as well as Malaya and Singapore if that became feasible).

Revolutionary factions in Borneo had been receiving covert Indonesian support for some time under the umbrella title of the North Kalimantan National Army (NKNA). The rebel forces consisted of some fifteen companies of 150 men, armed with shotguns, parangs, axes and spears, under the leadership of A.M. Azahari. The Squadron was fortunate in having the 14 Flight detachment more or less on the spot (at least in the same country) and in a very short time the anti-pirate aircraft switched roles to become an anti-rebel aircraft and did excellent and timely work in the opening stages of the revolt. Meanwhile, there was furious activity at Kluang.

All the tedious air portability exercises paid off and Flights adjusted themselves to operate on light scales. 14 Flight moved first to back up their existing detachment. The Beavers flew direct over an uncomfortably large stretch of shark infested sea, while the Austers were brought by RAF transport. Most things worked like a charm and the Equipment Officer and his loading/lashing teams earned their pay. Little sleep and little food were had by everyone during these initial stages. On arrival in Brunei, the Flight Commander dashed out of his Beaver and smartly reported himself to the Brigade Commander, and was ‘uncharitably engaged’ by a rebel machine-gunner from a roof top while he was in mid salute.

Corporals Les Rogers and Dick Jones hard at work servicing an auster of 14flt. in Brunei

The detachment was soon reinforced by several aircraft from 7 Flight, in the second week of December, the first to arrive being the ground party under REME Staff Sergeant Jack Greaves. Long-range fuel tanks had been fitted to the three Austers to enable them to fly 800 miles across the South China Sea, from Singapore to Kuching on the coast of Sarawak, and onwards to Brunei. The over-water sector was some 450 miles and was escorted by a Shackleton from No 205 Squadron. Also included in the formation were Single Pioneers and Twin Pioneers of No 209 Squadron. This was a calculated risk with a narrow margin of error – with a five knot headwind the aircraft would not have made it. Another factor to consider was that as the engine was inverted, if the oil loss was anywhere near the maximum allowed, the oil level would reduce below the minimum, risking an engine failure.

The weather turned torrentially wet in the New Year and flood relief was added to the growing list of tasks. 14 Flight would spend eight months in Brunei before being relieved by 11 Flight, which was dispatched to Sarawak, where further trouble had flared.

By the end of February 1963, the initial and localized revolt in Brunei and Sarawak had been put down. However, by the end of the year, 7, 11 and 16 Flights were deployed on operations, with 14 Flight resting and retraining at Kluang. Where possible, a system of reliefs was operated, allowing a maximum of three months on operations and then a break for R & R in Malaya. More than 8,000 hours were flown during the year, with nearly half this total being operational.

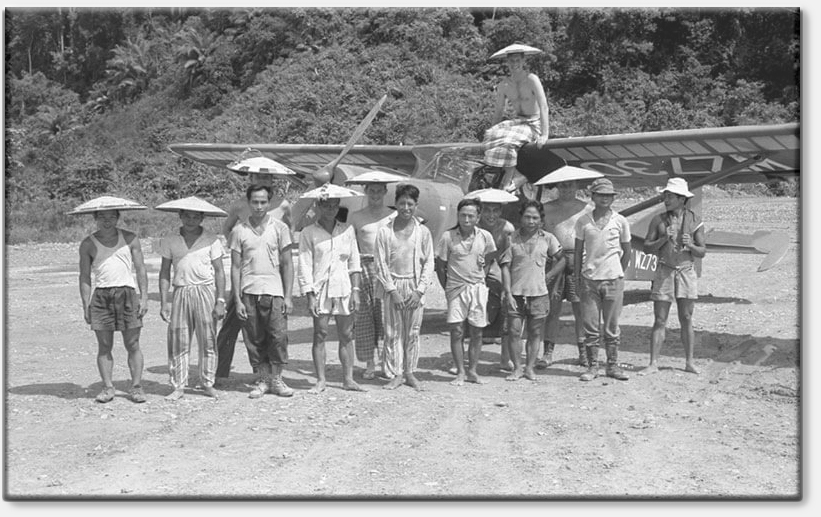

Members of 7 Flt. detachment pose with Iban workers at Belaga in Oct 1963

Confrontation

It was, however, only the beginning. The policy of ‘Confrontation’ instigated by President Sukarno of Indonesia, would commence following the establishment of the independent Federation of Malaysia in September 1963. Two of the constituent parts of the island of Borneo, which lies 400 miles east of Singapore, had joined the Federation as East Malaysia; Sabah and Sarawak, which had together formed the Crown Colony of British North Borneo. Sandwiched between these was the independent Sultanate of Brunei, which was a British Protectorate.

The bulk of the island, Kalimantan, was part of the Republic of Indonesia, which deeply resented the establishment of East Malaysia. A frontier of nearly 1000 miles stretched between the four territories, with ground heights up to 13,000 feet, few roads and an abundance of featureless primary jungle. A good description was given by Captain Tim Deane of 7 Flight, which served in Brunei from December 1962 until mid-January 1963 in close support to the Queen’s Own Highlanders and at Kuching in Sarawak from May 1963 to October 1964 as a full or part flight,

‘The terrain is characterized by dense virgin mountain jungle in the interior reaching to 9000 feet and more, falling away to a wide strip of coastal swamp. Most of the country is uncharted and no topographical information is given on any map outside the centres of population. Generally, the people fall into two categories: the educated and trading Chinese who have settled in the more developed area and the Borneo tribes – Ibans, Kyans, etc former headhunters who live in the interior. The only lines of communication are the great rivers which dominate the country. Roads are almost non-existent, except within the towns. There are no railways. Rivers are the lifeblood of the country, and the vast majority of the tribes live in community longhouses along the banks of these great chocolate coloured turgid streams.

In the thousands of square miles of mountainous jungle separating the rivers, no sign of human life is ever seen from the air. The climate is similar to Malaya and generally conforms to the pattern of fine mornings after the clearance of dawn mist or fog, building up in the afternoon and evening to immense thunderstorms. This pattern, however, may vary considerably, especially during the monsoon period, when the rainfall is more widespread and unpredictable.

Borneo has one of the highest annual rainfalls in the world, rivers commonly rising 20 or 30 feet overnight in the rainy season.’

As we have seen, the trouble started late in 1962 with an internal revolt in Brunei, which was rapidly suppressed. Britain was fully ready to meet its obligations to deal with any internal subversion or hostile incursion and to this end appointed a Director of Operations in Borneo, Major General Walter Walker. Indonesian raids on border police posts began in April 1963.

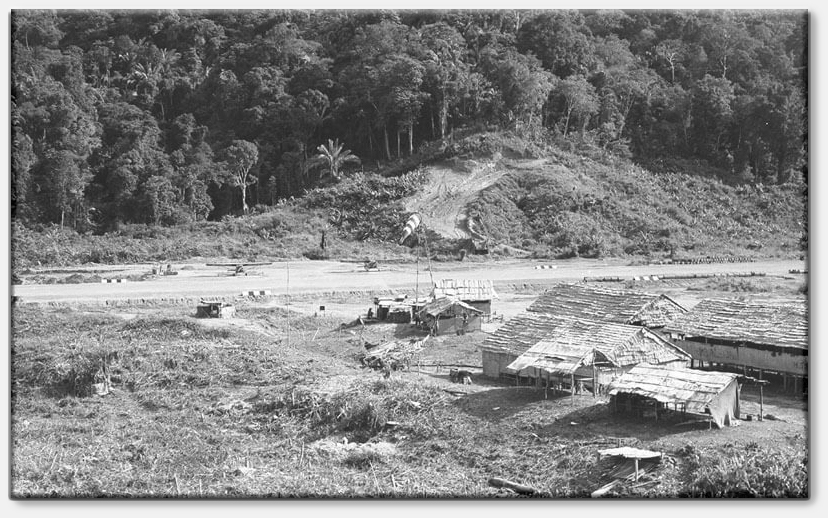

Airstrip at Balaga Nov 1963. Note Austers parked in the background.

Thereafter, the offensive activity by the Indonesians chiefly consisted of incursions along the border, which amounted to an undeclared war. The Army was deployed all along the Kalimantan border in a chain of forward bases from which patrols were made. Helicopter landing points were constructed every thousand yards or so for the purposes of resupply, troop movements and casualty evacuation. As roads were virtually non-existent, the importance of the helicopter can hardly be overemphasized. Food, water, kerosene and ammunition were supplied to the bases daily. Troops could be airlifted rapidly to border crossing points where incursions had occurred.

Flexibility in response to fast developing local situations and central tactical control of the bigger picture were the key factors in utilizing aviation resources efficiently. The weather was an important factor in dictating the level and intensity of flying activity. Morning mist and low cloud was frequent and tenacious, the afternoon thunderstorms were widespread, regular and heavy. A further factor to be considered was balancing fuel against payload, as refuelling was available at the jungle clearing bases in cases of emergency only. Lieutenant Colonel Begbie provided a very succinct summary of the necessity of air support in the FARELF Army Aviation Newsletter No 1 of 1964,

‘The primary role of Army Aviation in Borneo boils down to one thing and one thing only – to give support to the troops on the ground in whatever form they need it most. Without aircraft to provide logistical support and tactical mobility it would be impossible to maintain control over most border areas in Borneo. In the Central Brigade area for example, the infantry battalions and their supporting Scouts and Whirlwinds, deployed in the interior, have no surface L of C whatsoever and depend entirely on air supply for their existence.

In these areas AVTUR, rations, ammunition and other stores are delivered by parachute, while Pioneers, Beavers and short-range transport helicopters are fully committed to the movement of personnel and the recovery of parachutes and containers for reuse. In few forward areas are light aircraft strips capable of redevelopment to accommodate Beverleys from No 34 Squadron [or later No 215 Squadron with the Armstrong Whitworth Argosy]. Distances, terrain and the continuous air support necessary in all battalion areas has led to a general forward deployment of aircraft to minimize response time and the distance to be flown on each task.’

With the year of 1963 drawing to a close, Sergeant Dave Thackeray of 7 Flight was involved in a serious incident in the border area in Borneo. He was engaged in dropping mail to a forward detachment when his Auster came under Indonesian fire from the ground. His passenger was a senior RAF chaplain, Wing Commander A.M. Ross. Both were hit and wounded.

Thackeray was losing a lot of blood, his passenger’s wound seemed serious and he was forty minutes’ flying time from the nearest airfield, so he elected to land on a space cleared for helicopters. On his first attempt he felt a bone in his left arm break, rendering it useless. He had to take his right hand off the throttle and juggle with the stick in that hand and between his knees, as he made two further circuits. He judged his final approach so well that the aircraft came to rest with comparatively little damage. Before fainting from loss of blood, Thackeray drew the attention of those clustering around to his critically wounded passenger, who sadly died before he could be lifted out of the cockpit.

The pilot was Mentioned in Dispatches and also received a Green Endorsement in his logbook for airmanship. As it entered 1964, the Squadron could anticipate six major challenges. Firstly, involvement in the Confrontation – during the year nearly all the Squadron’s pilots and ground crew would have tours in Borneo, which would evolve into a regular pattern whereby two flights would be in Borneo and two in Malaysia, rotating every three months.

Secondly, the introduction of the Westland Scout AH1 helicopter to replace the Auster. Thirdly, reorganization of its structure to provide flights organic to formations and sub-units integrated into teeth arm units (Air Troops or Platoons). Fourthly, planning for the assumption of responsibility by the Royal Army Service Corps for the manning of fixed-wing aircraft, which in the case of 656 Squadron would be 30 Flight with Beavers, and also, fifthly, for REME taking complete control of reorganized aircraft workshops.

Finally, there was the plan that the Squadron would evolve into a Wing as part of GHQ of Far East Land Forces. This proposal resembled earlier wartime discussions, which similarly never came to fruition. In February, 11 Flight set off on a three month tour, with a Beaver and Auster section operating in Tawau in the north-east against Indonesian infiltrations and the rest of the Flight taking over the usual duties from 14 Flight. The Beaver was proving itself to be a very valuable workhorse that everyone came to rely on. Meanwhile back in England, on 02 March, a formation of sixteen Scouts departed Middle Wallop, the first to be sent to the Far East. The Director of Land/Air Warfare, Major General Napier Crookenden, flew in the leading aircraft. They landed on the commando carrier HMS Bulwark, which, four weeks later, arrived in Singapore, also bringing 10 Flight which had been loaned from 651 Squadron to join 656 at Kluang.

Scout XP888 landing at Gunong, Seperdang in Sarawak, a hilltop rebroadcasting station.

The Squadron was faced with the task of re-equipping the 7, 11 and 14 Flights with Scouts, acceptance checks, pilot training and rushing them to Borneo ‘all by this time yesterday.’ The fact that the dates were met reflected great credit on the workshops and the two flying instructors, WO2 Hutchings, and Major Woodbridge, who came out from UK. In addition to the pilot commitments, REME was very short of practised technicians and much appreciated the expertise of Joe Clixby of Bristol Siddeley, and Roy Allison of Westland, who worked very hard to get the Flight aircraft off to a good start and to pass on their experience to the technicians.

At this stage the Squadron had no indication as to the intensive maintenance effort this aircraft was to require. The five-seat Scout was the first British ‘home grown’ turbine-powered helicopter. In terms of performance it was a great leap forward. It was fast – over 100 knots – and had an impressive rate of climb, reaching 10,000 feet in less than ten minutes. Pilots, used to the underpowered Skeeter, found it a delight to fly and it would eventually prove to be both rugged and robust; but in its early years it was beset by numerous technical defects which resulted in very poor serviceability, which was a considerable headache for all concerned.

Early in April, 14 Flight was re-equipped with five Scouts and said goodbye to the Austers and Beavers which had undertaken sterling service in Borneo since the Brunei rebellion began. It got down to intensive training to be ready to move to Sarawak in June. Early in May, jungle survival courses were completed and towards the end of the month the Flight spent three days in the Cameron Highlands at 6000 feet, learning all about the problems of handling the Scout in the rarefied air. It was noted that,

‘Fresh strawberries and sleeping under blankets were an enjoyable change from the steamy heat of Kluang.’

In the second week the Flight had a signal from 28 Brigade, who were on exercise about sixty miles north of Kluang. Their RAF support helicopters had all broken down, they were desperate for water and rations, and had casualties in all three battalions in primary jungle. Four Scouts flew regular sorties over five days and supplied most of the Brigade by landing in very small jungle clearings. The Flight evacuated no less than seven serious casualties to the Field Hospital at Malacca on the west coast. It also carried out Air OP Shoots with 170 (Imjin) Battery RA, using their 5.5 guns on Asahan Ranges.

On the way back from the Cameron Highlands the aircraft were refuelled at Kuala Lumpur Airport and created quite a stir when they did a short flypast. In the same month, 30 Flight, which was staffed by RASC and AAC permanent cadre pilots in the main, the first integrated flight, was formed under Major John Riggall, taking over the Beavers operated by 11 and 14 Flights, with a base firstly at Kluang, but from July at Seletar. The Warrant Officer in charge of the Flight Workshop, which remained at Kluang, was a Chief Petty Officer RN on loan to REME, of whom John later wrote,

‘Twenty years of aviation experience and a refreshing attitude to Army methods made an invaluable combination.’

The new Flight undertook its first operation at 0800 on the morning of its formation, in lieu of a far more traditional workup period. The lack of either a clerk or a typewriter provided,

‘A first class excuse for not writing letters and HQ FARELF were remarkably courteous about receiving essential correspondence in long hand on a memo pad.’

It would soon find its assets spread across Malaysia and Borneo in four detachments, covering some 1500 miles,

‘Distances are huge. If Flight HQ was in London, our Workshops would be in Cambridge; Sibu is as far away as Berlin, Brunei as Trieste and Tawau as Tunis. Brigade areas are vast, five hours of flying at 125 mph showed four Major Generals, the Brigade Commander and a Battalion Commander, a considerable proportion of Central Brigade’s area in Brunei recently.

One Company Commander has a Company area rather larger than that of the Rhine Army. The airstrips vary from the very frightening to the very good.’

11 Flight returned to Kluang to convert to the Scout. It is of interest to note a comment made to OC 656 by Brigadier W.W. Cheyne, DSO, OBE,

‘I command my brigade with a Scout helicopter. I cannot do it any other way. There is no other way.’

Long Pa Sia

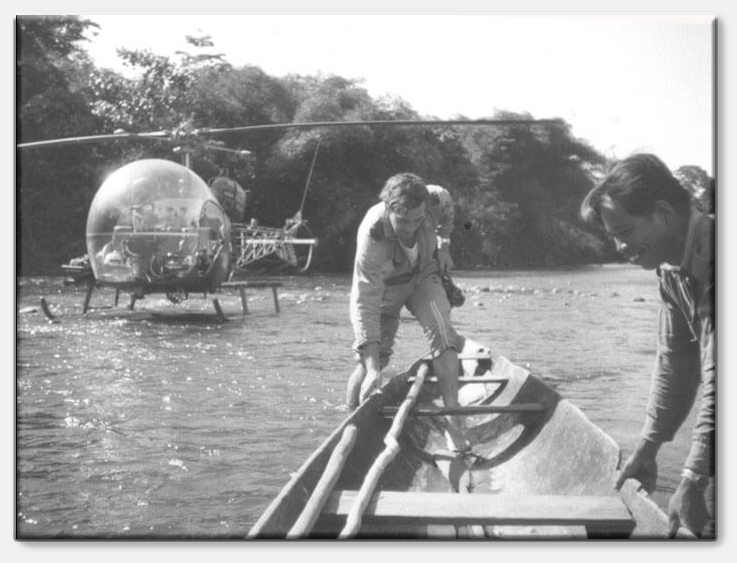

The first to occupy the Squadron’s jungle fort at Long Pa Sia in Borneo, was 10 Flight. This initial period lasted from June to August, and during this time the Flight had on its establishment five Scouts, six pilots, twenty-three ground crew (at various times a dog, an owl and a baby deer), and the only hot baths in Sabah! After two months work at Kluang, it had moved by way of the LST Empire Gannet to Labuan. There, the aircraft were flown off the deck of the LST, and on in formation to Brunei for three weeks operations before moving out to Long Pa Sia.

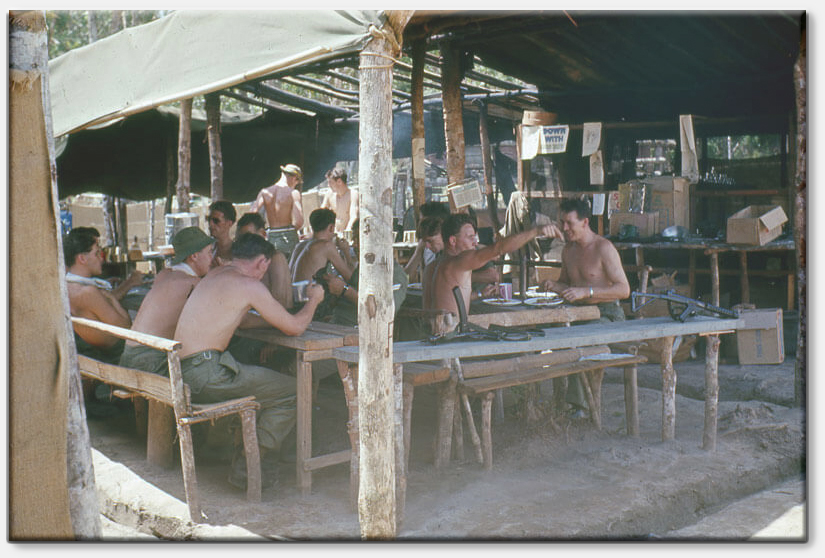

10 flt. personel in the mess tent at Long Pa Sia, Borneo 1964

Long Pa Sia itself was a small longhouse village, or kampong, on the Sungei Padas, tucked into the south-westerly corner of Sabah, about four miles east of the border with Sarawak and eight miles north of the border with Indonesian Borneo, although the Indon esians insisted that the Flight was only three miles north of their border – ‘a fact the Flight patriotically chose to ignore!’

The strip at Pa Sia was situated some 400 yards north of the kampong in the middle of dense primary jungle, and was only accessible by air, ‘unless one was prepared to accept a three week walk from the nearest civilization!’ It was surrounded by mountains on all sides which rose up to 6000 feet, and the runway itself had an elevation of 3275 feet, which made it a very pleasant climate in which to live.

Long Seridan was a typical jungle airstrip not far from Long Pa Sia in Sarawak; this photo was taken from Beaver XP817 in mid-1963

Fresh water was permanently available from the Padas which rushed past the strip and although this water was a bright orange in colour, it became quite palatable when, ‘diluted with a little of John Haig’s taste and colour-removing elixir!’ Fresh meat could be obtained by issuing one of the villagers with a couple of twelve-bore cartridges, though this practice could have had its perils as the locals were apparently fervid pro-Indonesians whose sole interest in the British Forces and Malaysia was one of finance.

Scout on a makeshift log pad at Long Pa Sia.

The flying task of the five Scouts was to support Central Brigade in any way that was asked, and this involved mostly freight-lifting, resupply, troop-lifting and communica tions flying. The camp itself was typical of the jungle forts which dotted the border in Sabah and Sarawak, and was built entirely of wood, bamboo and sandbags, with tarpaulins for the roofs of all the bashas. The initial construction work was to build an Ops Room and this, together with improvements to all the other bashas, a water supply for the Officers’/Sergeants’ Mess basha, communications trenches, bunker rebuilding, new latrines, a basketball court and sundry other building projects, ‘occupied most of the people for most of the time.’

All supplies arrived at the end of a parachute, and air drop days – normally a Friday – were the highlight of the week. On the whole, the accuracy of the RAF was of the highest standard, and not only had they to hit the strip with the one-ton containers; they also had to miss the camp and the parked aircraft. Apart from the odd one-ton’s worth of AVTUR that landed irrecoverably in the ‘ulu’, the only real tragedy was when the NAAFI supplies and fresh rations free-fell into the jungle one morning, and all that was salvaged were a few pencils and a roll of film. Beer and spirits of course, arrived in this way and thankfully were always recovered. Spirits were dropped in one gallon oil tins to avoid any possibility of breaking the bottles, and it was found that a can of Tiger beer would sustain a fairly hard blow before splitting.

Apart from the excitement of the weekly airdrop, the Flight was often visited by Gloster Javelin FAW 9 delta-wing fighters of Nos 60 and 64 Squadrons which patrolled the border daily, and they were only too glad to use the Pa Sia low flying area when requested over the radio to check the strip. Some of their low flying passes were quite memorable, particularly,

‘if it was remembered that there was a 6000 foot jungle-clad alp at the north end of the strip, and a Javelin doing an emergency turn on full reheat was quite a sight!’

Invariably, a platoon or patrol position, indeed even some company positions, were situated in clearings in the jungle, and these clearings posed many problems for those flying into them. Owing to the altitudes in volved, and the fact that the aircraft were always used to the full and were loaded up for every trip, a great deal of the clearing work was done on limited power.

The Scout, being small and highly manoeuvrable, enabled pilots to get in and out of clearings that the RAF’s Whirlwinds would not consider, and even then it was not always possible to land owing to tree stumps left in the bottom. The height of the trees surrounding these clear ings could be more than 200 feet, and more often than not there was only one way into a valley, and the same way out again,

‘Still, the Scout always obliged pilots by flying for long periods on 100 per cent, everything, and the standby power check of “the more you sweat, the more weight you lose, thus the more power that becomes available” got most of the pilots out of hot, high clearings at one time or another.’

In June, all five Scouts of 14 Flight were flown down to the Empire Dock in Singapore. They landed alongside the Empire Gannett, the blades were folded and the aircraft hoisted on board in no time at all. The pilots would have liked to land on, but the Port Authorities forbade this because apparently the dock would have lost the handling charges. They arrived at Kuching on 19 June and flew off – the first time an Army Air Corps Flight had been launched at sea as a unit.

The first few days in Kuching were spent being shown round the area by the OC, Major J.L. Dawson, who had previous experience with 7 Flight, and the Whirlwind pilots of 225 Squadron. The latter shared the Royal Green Jackets’ Mess with the Flight and Belvedere pilots from 66 Squadron.

The Flight’s role was to support West Brigade in Sarawak from Kuching Airfield, about five miles south of the town itself. West Brigade, with five battalions on the border, was responsible for aiding the civil powers in keeping order, not only against the bands of Indonesian infiltrators on the border itself, but also against a large number of the CCO (Clandestine Communist Organiza tions), Chinese immigrants who lived and worked in the territory. Roads were few and far between, the local popula tion inland consisted of land or sea Dyaks – the Ibans, former headhunters, who ‘unfortun ately appeared to be returning to their old sport’ in parts of Sarawak.

This part of Borneo had few mountain ranges, most of the area was, or had been cultivated, so there was a great deal of secondary jungle and scrub. The only recognizable features from the air were the hills and often these were great slabs of limestone with vertical faces, full of caves and stalagmites. A large number of clearings and helicopter pads had been made in the border area; all these were numbered and it took the pilots’ days to plot them all on their maps, not to mention the inevitable amendments. Indonesian raids by regular and irregular troops continued in the border areas, on forward platoon bases and even unprotected kampongs. There were occasional diversions, as on 13 July when,

‘One aircraft was flown up to the beach for a compass swing near an old Japanese fighter airfield. Staff Sergeant Bushby was the pilot and the aircraft returned loaded with ripe coconuts!’

Back in Malaya, the Squadron sustained its first fatal helicopter accident on 15 July, when Captain Daniel Jacot de Boinod and flying instructor WO2 W.J. Hutchings, were killed in the crash of Scout XR596. The cause was mechanical failure and could be directly attributed to the hasty introduction of an unreliable and untried aircraft in to an operational theatre. The only positive benefit was that this tragic loss spurred on efforts to improve the Scout.

Needless to say the work of the Squadron carried on. For example, on 17 July, a Scout piloted by Captain L.C. Bond flew forty miles out to sea, touching down on HMS Bulwark to collect the pilot of an Auster who had just landed on board, the aircraft was en-route for the Squadron Workshops in Malaya, and on 21 July, a number of gun registration sorties were flown, as well as the air observation of 3 inch mortar shells for the Green Jackets.

The AOP shoots took a standard form. The pilots landed at the forward base and collected the Platoon Commander who sat beside the pilot, and he could point out the track, junction or stream from low overhead. The aircraft then retired to a safe fly line to engage the target. This method definitely paid dividends since enemy casualties after one ambush were credited to accurate target registration. In August, much to the frustration of all, the Scouts were grounded for nearly ten days due to serious Nimbus engine problems.

Aircrew spent the time acting as second pilots on the Whirlwind Mk 10’s of 225 Squadron, helping them on tasks. The majority of the flying was to forward areas with company and battalion commanders, whose headquarters were between twenty and forty miles from their platoons on the border, flying over primary and secondary jungle where roads were non-existent and the whole battalion forward was dependant on air supply. When the Scouts were back in action again, one from 14 Flight was detached to the Royal Ulster Rifles at Serian, about forty miles south-east of Kuching,

‘Captain Bond was sent there at first, because despite the fact he lives in County Cork, it was thought he could at least speak the same language.’

In mid-August, 10 Flight was relieved by 11 Flight at Long Pa Sia, before returning for its second three months’ spell in November. Towards the end of the month, on 27 August, a report from Serian noted that the detached Scout had completed sixteen sorties in one day, which included a mortar and ammunition flight and the seven-man Combat Tracker team and their dog. At the beginning of September the Indonesians carried out a parachute drop in the area of Labis, about 40 miles north of Kluang.

The Squadron was called into operation and 10 Flight, which had, of course, just returned from Borneo for a rest, found that it had been curtailed. In addition, two Austers from 16 Flight were sent down to help out. Back in Borneo on 11 September, Sergeant Hall from 14 Flight conveyed an assortment of Padres round the Green Jackets’ bases – ‘It was rather difficult deciding which denomination to put in the front seat.’ The engine trouble continued and a Beaver from 30 Flight RASC, flown by Captain D.A. Beechcroft -Kay, was sent to help out 14 Flight, as at one stage it only had one helicopter flying. On 01 October, 16 Flight officially disbanded and became Air Troop 4 RTR (Royal Tank Regiment), moving their location from Ipoh to Seremban.

They would continue to fly Austers in Malaya and Borneo until their Sioux helicopters were available and would be the only formation to keep its Austers throughout the Confrontation, except for a detachment on loan from 20 Independent Recce Flight in Hong Kong. The Squadron was now busily engaged in its seventh major task, the preparation for the arrival of the Sioux and dispatching the unit’s flights.

The American-designed Westland Bell 47G Sioux light utility helicopter had been purchased by the AAC to supplement the troublesome Scout. It was produced under licence by Agusta in Italy and by Westland at Yeovil, some 150 being delivered to the Army, the first British built example flying in 1965. The plan was to embed sections of Sioux as Air Platoons, or Air Troops, into individual fighting units within the Order of Battle. As the New Year of 1965 dawned, the Squadron was:

(a) Preparing a flying training programme of 600 hours (for which flying instructors were flown out from the UK and another brought in from 20 Flight in Hong Kong).

(b) Assembling five newly-arrived Sioux, compete with the examining team.

(c) Preparing for the Administrative Inspection.

(d) Getting the Scouts flying with a modicum of safety.

(e) Administering two AAC Flights in Borneo, which should have been taken over by their respective Brigades in May. (f) Tackling day-to-day problems.

It promised to be another busy year. The situation in Borneo remained highly volatile with the prospects for a negotiated peace not looking promising. On 13 January, Government authority was given to extend the Claret ‘hot pursuit’ policy, up to 10,000 yards across the border with Kalimantan, from the previous limit of 3000 yards.

This extension of offensive patrolling was not widely publicized, as open and declared warfare was the last thing that the British, Malaysian, Australian or New Zealand governments wanted. The desire was to persuade the Indonesians to desist by maintaining a stance that would convince them any provocation would meet a firm and appropriate response. The incursions would continue by land, sea and in the air, but without any significant effect.

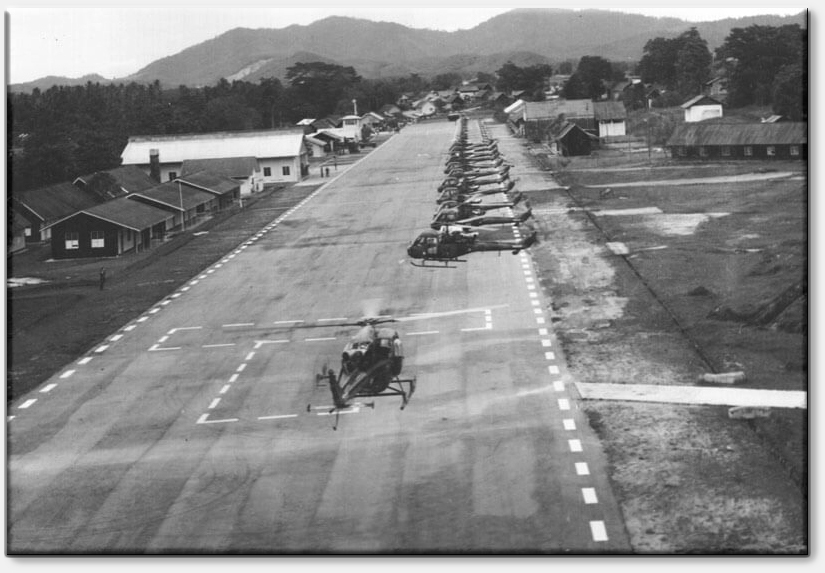

The first Sioux arrived in Singapore in February 1965 and were handed over to the RAF MU at Seletar for assembly. As there was a certain amount of impatience to start operations with these new arrivals and as the MU was hard pressed with other work, scratch teams of technicians were provided by REME from the Squadron Workshops to help. On 10 April 1965, the first Sioux-equipped air platoon was operational at Kuching.

At a Guest Night at Middle Wallop in February 1965, Colonel Denis Coyle, as the first commander of 656 Squadron, accepted, on behalf of the Officers’ Mess a magnificent silver model of a Scout. This was handed over by Mr H. Winkworth of the Westland Aircraft Company, and was a joint present from Westland, Bristol Siddeley Engines and Lieutenant Colonel P.E. Collins, and the officers of 656 Squadron. The Ceremonial Malayan Kris given by the Government of the Federation of Malaya to commemorate 150,000 hours of operational flying, was also taken into safe custody by the Mess at the same Guest Night.

1965

Meanwhile back at SHQ in Malaya, 1965 was described as ‘a year of stimulating expansion.’ It was noted that,

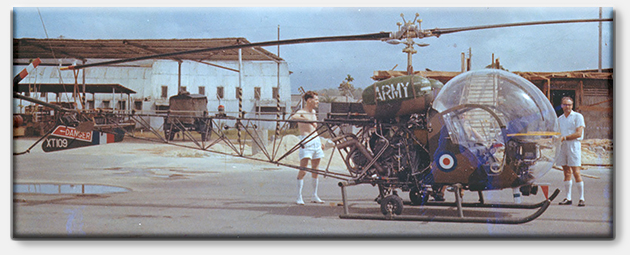

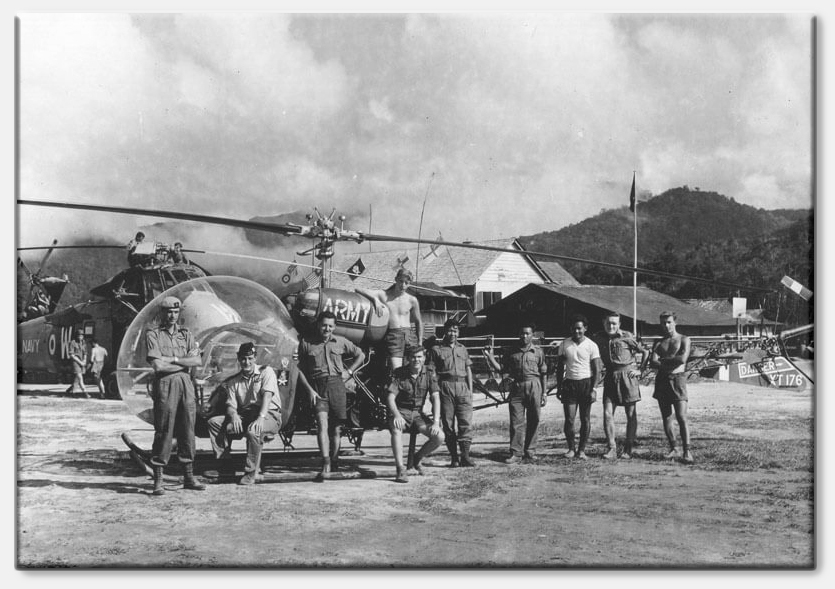

‘The number of Army aircraft flying in the Far East had more than doubled and further increases were due. This number included helicopters on which the ARMY marking has been cunningly altered to RM, as the Royal Marines entered the field for the first time under the wing of Army Aviation – this despite some rather “old-fashioned” looks from the Senior Service.’

The Squadron and the REME Workshops would support the four Air Troops of 3 Commando Brigade, which were each equipped with three Sioux. The deployment of steadily increasing numbers of Sioux was the most important development of the year. Progress was remarkable in spite of obstacles of all sorts, due not only to technical and logistic problems, but also to the fact that Army Aviation was breaking entirely new ground. Raising and training of air troops/platoons was undertaken at Kluang, initially under HQ 656 Squadron and later the Wing Flying Training Element.

The Sioux was introduced into Malaya in 1965.

Throughout the year the hard working flying instructors and fitters worked under considerable pressure to turn out the finished products on time. To launch newly trained air platoons into Borneo, untried and still lacking full technical and spares backing was also something of a risk. After all the difficulties with the introduction of the Scout Army Aviation they could ill afford another setback, but as the situation on the ground demanded more helicopters, so in they went. Battalions certainly had to contend with many difficulties, which were highlighted by the signals which flooded into Squadron HQ,

‘One air platoon, remote in north-east Borneo, received an unwanted Land Rover Mk 4 radiator, issued by some mischance in mistake for a precious ARC 44 radio; another had no Air Publications, so how could it answer signals about part numbers; others impatiently await the “automatic” initial issue of G 1098 stores [tools and equipment] which, for some reason, seemed to have reverted to manual; and “why can’t the Army Air Corps …” and so on. And still, pushing urgently to the top of the piled-up IN trays in the headquarters, came those ominous signals stamped OP IMMEDIATE and starting off “Scout serious defect,” though admittedly there were not so many of them these days.’

In spite of all this the Sioux was a success from the start. Enthusiasm in the Air Platoons was high, serviceability had nearly always been good and the helicopters were of great value to those regiments and battalions fortunate enough to receive them. Logistic support was now improving and HQ thrashed out problems of control, including the responsibilities of Aviation Commanders, while also making clear which Service commanded the Army’s aircraft in the field.

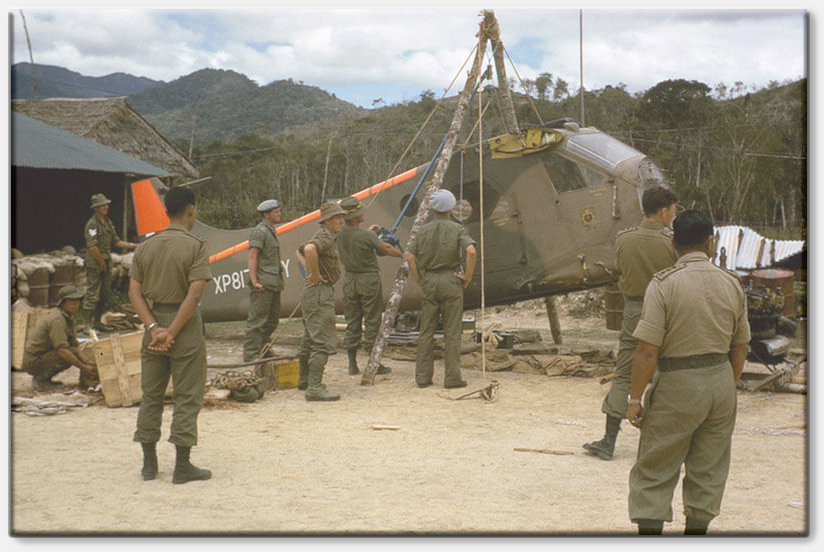

Recovery of Beaver XP817 in Bario, Borneo, in early 1965

From the start of February, 30 Flight came under the command of 3 Army Air Supply Group. The Flight would be renamed 130 Flight RCT in July, following the creation of the Royal Corps of Transport, but continued to carry out its duties as theatre Beaver flight with detachments in Brunei and Sabah.

The Beavers undertook a wide variety of tasks including the delivery of men and materials, VIP in-theatre transport, casualty evacuation, search and rescue, aerial photography, visual reconnaissance, observation by brigade or battalion commanders, Air OP for artillery batteries and warships, dropping supplies, leaflets and flares and even free-fall parachute training.

There was even the opportunity for one Beaver to land on the deck of the aircraft carrier, HMS Hermes. On one occasion, due to a shortage of Twin Pioneers, the Beavers carried out a full company changeover; 400 troops and a considerable quantity of stores were lifted in the course of 161 sorties over a period of a week in 100 flying hours. In John Riggall’s opinion,

‘The Beaver is probably the most efficient aircraft the Army has had. Reliability has been one of the main factors in its success. Much of the credit is due to the very long hours of work by the REME technicians, and perhaps most important of all, much thought and planning by the Chief Petty Officer to achieve a good servicing stagger and anticipate trouble before it occurred. None of this would be possible without a basically sound, rugged aeroplane.’

At the end of May, 10 Flight returned to Borneo for its third tour on the island and was based at Brunei Airport rather than at Long Pa Sia, as in the past. The main reason for this change of base was an attempt to improve the serviceability of the Scouts, the lack of readily available spares, plus the inability to work at night at Pa Sia. It was hoped to overcome these snags by moving to Brunei; 11 Flight had three months and three weeks to put the theory to test.

Lt John Charteris picks an unusual landing site for his Sioux in Borneo

On serviceability, it took a little while for the improved servicing facilities offered at Brunei to start to show fruit. The ground crews worked wonders through many a long night and always produced serviceable aircraft in the morning. It became so regular a matter to have four aircraft tasked every day that,

‘the Flight pilots started to complain at the excess of flying that had to be done; the first time such a complaint had been heard in this Flight!’

The average sortie time, operating out of Brunei some eighty miles from the border, was unchanged at twenty minutes, compared with the average time out of Long Pa Sia only eight miles from the border. The tasks carried out by the Flight during this tour were as varied as before, including, recce, casevac, communications, troop lifts, photo recce, Forward Air Control, freight lifts, plus a small amount of training and a deal of air-testing. The leading statistics showed:

Hours: 654

Sorties: 1,799

Passengers: 2,744

Freight: 182,629 lbs.

Casualties: 29

The main tasks were still troop lifting and freight moving, the daily record for both being ninety troops and 18,000 lbs of freight. The aircraft also moved several 105mm howitzers with ammunition and personnel, plus other sundry items of freight. Staff Sergeant Overy arrived at Long Banga one day to discover that there was about 10,000 lbs of RE plant twenty miles away that was urgently required for the rebuilding of the Long Banga airstrip.

The RN had been tasked to move this plant with Wessex HU5s, but had not turned up as yet. Staff Sergeant Overy broke it down into Scout-type loads, hung it beneath his aircraft, and ferried it the twenty miles in nine trips. The Flight also had its moments with 24 Construction Squadron of the Royal Australian Engineers. They were building a road through primary jungle between Kenningau and Pensiangan in Sabah, and on several occasions had cases of appendicitis to evacuate. These never became apparent until late in the afternoon, and it was invariably Major Benthall’s lot to go out the odd 100 miles to collect them. The race was then on to arrive back in Brunei before dark; which must have been the only international airport in the world without a single navigational aid.

Only once did he return well after sunset (with no landing lamp and two mile visibility in haze). However, the Flight switched the lights up in the bar, and this illumination, together with the light cast by the starboard navigation light, was sufficient for a safe landing to be made. The never ceasing ‘hearts and minds’ campaign continued, the Flight’s main contribution being twofold:

First, they carried out many civilian medevacs and casevacs from remote kampongs in Sabah, Sarawak and Brunei States, transporting them mainly to the Government Hospital in Brunei and returning them when cured (or otherwise) back to their homes.

Second, they flew Army vaccination teams around the countryside to immunize local people against a variety of diseases. Two trips of this nature were undertaken, visiting ten villages and injecting some 2,000 people. The pilot was an invaluable member of the team, assisting on the production line by swabbing arms or charging hypodermics.

The Flight was visited by several notable people, one of the most welcome being the Commander, Brigadier Harry Tuzo, OBE MC,

‘always a stalwart and knowledgeable supporter of Army Aviation, the Commander visited the Flight on several occasions and always expressed a preference for Army aircraft on all his many journeys around the Brigade, which covered an area about the size of Wales.’

The AOC 224 Group, Air ViceMarshal Christopher Foxley-Norris, spent some time listening to the Flight’s problems in August, as did several Army Aviation and RAF Evaluation and Stores Acquisition teams. It was hoped that the Flight would get all the spares and new types of aircraft they required as a result; the most important being a comfortable, sensible, up-to-date and efficient form of pilot’s microphone,

‘one could gauge the popularity and efficiency of the issue throat microphone by the number of pilots wearing home-made and locally “modded” boom mikes.’

During the tour there was not a lot of time for organized relaxation owing to the intensity of the flying effort. However, the Flight found time to visit Muara Beach on several occasions for water skiing, and made a visit to the oilfield at Seria. For pilot relaxation, Lieutenant Pyke and Staff Sergeant Overy undertook a river ‘patrol’ in a longboat. An 18 hp outboard was borrowed from the RE Port Squadron, and in a boat heavily laden with food, petrol, beer and blankets, a trip up the Limbang was achieved.

The major political development during August was the not entirely amicable withdrawal of Singapore from the Malaysian Federation by means of the Separation Agreement which, however, maintained civilized relations, trade agreements and mutual defence ties. Singaporean troops would continue to serve in Borneo. Meanwhile, 7 Flight spent six months in Sarawak, based on Kuching Airport.

Serviceability of the Scout had improved and at one stage in August they had all four aircraft serviceable at the same time. Sergeant Markham was subjected to a very harassing few minutes in July, when, over primary jungle and 4000 feet peaks, his engine stopped. By using great skill and making best use of any available glide, he managed to put the helicopter down in the only small patch of secondary jungle in the area. His four passengers, a major and three subalterns, were uninjured, except for one bruised back. After landing, Sergeant Markham set his passengers to work clearing the area around the Scout in readiness for the arrival of the rescue aircraft.

The unit knew the area he was operating in and the search aircraft found them and lifted them out to Kuching. ‘Very well done’ and ‘above praise’ were some of the comments made by the passengers. The Scout was recovered later by a Belvedere. Sergeant Markham was awarded a Green Endorsement for his handling of the emergency.

The Squadron suffered another loss on the night of 19 September, when Sergeant D.J.P. ‘Doc’ Waghorn, of 7 Flight was flying in the Kuching area with a Gurkha and a prisoner in the Scout XR599. It is thought that the aircraft crashed into the sea. Bill Morgan, who flew with both 7 and 14 Flights had very few good words to say about the Scout in its early period of service,

‘The Scout was a disaster from day one, the “fracto” Nimbus 102 engine was unreliable and we had two Rolls Royce engineers attached on site to keep things going. They were carrying out major engine rebuilds in the field.

Whilst in UK on training we were not allowed to fly over woods, yet in Sarawak it was 99.5 per cent woods in the shape of solid jungle. We never got anywhere near the target 150 hours engine life out the Nimbus and, to add insult to injury, one arrived flown in from UK, marked “temperate climates” only. The later Nimbus 105 post Mod 664 engine was hardly any better. We also had a problem called lateral shake, whereby the helicopter’s tail boom twitched. Damper units were fitted, but this made little or no practical difference. We spent many hours doing flight idle descents from about 10,000 feet to try and adjust the dampers. Much later it was discovered that there was a design fault in the free turbine which caused the vibration.

Scouts were deployed at forward locations with units near the border, crewed by a pilot and a mechanic. The crew stayed forward until the aircraft needed a thirty hour service when they were flown back to Kuching. There were not enough tools to cover these deployments, so we had to go to Kuching Town and buy extra spanners etc out of the PRI funds.

Often, when all the Scouts were grounded, I flew in the second seat in a Handley Page Hastings of No 48 Squadron. The RAF needed two pilots when they flew within range of the Indonesian AA guns on the border. They only came out with one pilot per aircraft, so they offered to basically train any AAC ex-fixed-wing pilot to bring the Hastings back to Kuching and land it in an emergency. For a couple of months I had more fixed-wing hours than helicopter ones!’

11 Flight spent June, July and August back in Kluang.

In the aftermath of what was claimed to be an attempted coup by the Indonesian Communist Party in Jakarta on 30 September and its brutal suppression thereafter by the Army, executive power slipped away from President Sukarno. Moreover, the country was beginning to suffer an economic downturn.

Slowly but surely the steam began to go out of the Confrontation. On 01 October 1965, after more than twenty years of eventful service, the focus of Army Aviation in the Far East was changed as the Squadron completed its reorganization to form HQ 4 Wing Army Air Corps at HQ FARELF and HQ Army Aviation, Borneo (which retained the title of 656 Squadron, in Labuan).

The event was marked in Kluang with several good causes being supported, the aim being to perpetuate the name of the Squadron in Malaya. Firstly, a cheque for $3000 was presented as the initial donation to an appeal for funds to build a Christian church in Kluang. Secondly, a cheque for $3000 was presented to the Chinese High School, and this money was used to furnish a new basketball court, which was named after the Squadron, and which was opened officially on 26 September 1965. A plaque at the side of the court bore the 656 Squadron Crest and a suitable inscription. Thirdly, a cheque for $3000 was presented to the Jubilee School, which was an English speaking establishment in Kluang and whose headmaster, the Reverend Victor Samuel, was an officiating chaplain to the Forces. This cheque was presented by Major General Napier Crookenden on 16 December 1965, during a visit to the Squadron.

During the final thanksgiving service in the Garrison Church, a memorial plaque was dedicated to the memory of Captain Jacot de Boinod and Warrant Officer Hutchings, who lost their lives in an aircraft accident on 15 July 1964.

Wing HQ was installed in Singapore as an integral part of GHQ, FARELF, with staff responsibility for aviation affairs throughout the Theatre. The Wing Flying Training Element remained at Kluang, together with the Theatre Flight AAC (a role undertaken by either one of two Flights, depending on which was in Borneo). This Flight was directly controlled by Wing HQ and was locally administered by 75 Aircraft Workshops REME, also based at Kluang and with detachments in Borneo.

One of the young pilots visited by Patrick and Ford was Lieutenant John Charteris of 4 RTR Air Squadron. He had a very high regard for them both. It is not recorded what they thought of John’s habit of taking two pet companions flying with him in his Sioux, a Gibbon by the name of Shack and a Hornbill called Wilbur. One of Shack’s favourite tricks was to jump up and swing from the swash bar as the rotor blades wound down.

The very well received Hearts and Minds Campaign involved bringing doctors or dentists to the native villages. Lieutenant Colonel Collins fully endorsed these sentiments and added that it was the technicians who bore the brunt of the frustrations and enormous extra workload arising from the frequent unserviceability and technical unreliability of the Nimbus engine.

He mentioned in particular one young sergeant, who had supervised the changing of no less than eighty engines during his two and a half-year tour,

‘In doing so he handled £2,000,000 worth of equipment in new engines alone and one can double that figure as each change was replacing one for one. Many times he and his team worked through the night and frequently in conditions of appalling discomfort. They never made a single mistake.’

On New Year’s Eve 1965, Colonel David Bayne-Jardine arrived as Commander Army Aviation FARELF, and in due course Lieutenant Colonel Collins set off to form HQ Army Aviation Borneo at Labuan, which had ‘the unique distinction of being the only Army Aviation HQ supporting a formation engaged in active operations and separated by twenty miles of sea and ten miles of land from the nearest army aircraft.’

Other changes were afoot; 20 Flight in Hong Kong and the Air Troops were brought within FARELF Army Aviation, the Work shops, which had reorganized on to a REME establishment and were now called 75 Aircraft Workshops REME. The title of 656 Squadron and ‘virtually nothing else’ moved with Collins. So for a while, 656 Squadron existed more in spirit than reality, although that spirit burned bright in the detached flights throughout the region.

While the Flights were now all supporting Brigades, it was generally agreed that whichever Flights were in Borneo were under command of the Commander Army Aviation, Borneo. Colonel Collins wrote that,

‘The cold English winter drove out the usual migration of visitors to Borneo in numbers so large that at one stage they represented a greater threat than the Indonesians.

The Brigadier Army Aviation [Brigadier C.D.S. Kennedy] cleverly chose a quieter moment in the spring and had an interesting but short tour round the main areas of activity. This time we managed to show him some characteristic weather when his first sight of Kuching airfield was in thick rain from a low-level fly-past downwind at a ground speed of 100 knots with a large storm closing in around us, and the pilot at the controls of the Beaver murmured “I don’t think I’ll land here from this approach.” An Auster coming in from the opposite direction just made it and so did we some fifteen minutes later.’

He was highly appreciative of the contribution made by the Austers in Borneo,

‘The usefulness of the Austers is undoubtedly overshadowed by the more dramatic roles played by the Scout and the Sioux, but there is little doubt that fixed-wing light aircraft still have a major part to play, particularly when flying hours can be had at such a relatively low cost. And where there is no danger from an enemy air force, the fixed-wing light aircraft is probably still the best vehicle to provide continuous surveillance of the battlefield.’

There were several other items of note, the first of which was something of a nuisance. During the early part of the year, with hostilities still in full swing and new air troops/platoons forming, the Sioux fleet was grounded for a while with torque tube troubles.

One particularly unusual event took place just before 3 Flight’s departure from Borneo in the summer. Their Malayan honey-bear, ‘Judy’, who had been looked after by Airtrooper Kent was accepted as a gift by London Zoo who agreed to pay her air fare home. Judy made royal progress, receiving lavish press coverage in Singapore and Press and TV coverage in UK. The year followed much the same pattern for 10 and 11 Flights, rotating between Brunei and Kluang.

Having been on roulement since 1964, these three-monthly moves held few problems for the Flights, with the average handover time being reduced to about three hours. On the not so operational side, two pilots spent a day flying the Rt Hon. Denis Healey, MBE, MP, Secretary of State for Defence, and Air Marshal Sir John Grandy, KCB, KBE, DFC, Commander-in-Chief FARELF, plus their party and wives, on a series of visits to local longhouses. Owing to the importance of these guests, lavish parties were laid on by the local chiefs, and a fascinating and enjoyable day was had by all.

Unfortunately, the two pilots were unable to partake of the customary vast quantities of rice wine because of the ‘Don’t ask a man to drink and fly’ campaign – but this enforced sobriety did not absolve the two concerned from their duty in performing solo native dances for the benefit of the Minister and his friends!

The Scout was a very popular aircraft with RE survey teams and many hours were flown helping to map the country. A lot of this required maintaining a lengthy free-air hover at heights in excess of 5000 feet while the surveyors took readings. The remarkable performance of the Scout in this aspect of flight enabled the job to be completed with relative ease. For 11 Flight, May brought a flurry of activity, with an incursion of Indonesians in the Bario area,

‘Once again, the speed of the Scout demonstrated itself when two Scouts were sent from Brunei, one as the Brigade Commander’s personal OP, the other for possible casualty evacuation. Time and again, the Scout had proved itself far superior to the Whirlwind 10 in any particular role in this theatre, carrying at least the same payload, but some 30 knots faster.’

The Flight also carried out FAC training with RNZAF Canberras on several occasions, with varying degrees of success. The main problem always seemed to be communications, but once a mutually satisfactory channel had been found, things proceeded quite well. It also started night cross-country flying, which was very successful and encouraging. It was generally felt among the pilots that, given good weather, night flights into the interior regions were quite possible. It summed up its time in Borneo,

‘The Flight was based in Long Pa Sia, a forward jungle airstrip, from August 1964, serving there a total of seven months before the Brigade Flight location was moved back to Brunei, where they served for a total of ten months. In that time they were employed mainly as part of the short-range transport force, flying almost 3000 hours all told – not an outstanding effort, but a worthwhile and satisfying one, reflecting credit on all ranks of the Flight, technical and otherwise.’

There was still time for the bone-shaking experience of flying between Malaysia and Brunei (in a Bristol ‘Frightener’ (170 Freighter) of the RNZAF, which was described as, ‘fifty-two hours of shaking, vibrating, sleepless cacophony from Brunei to Changi, or vice-versa.’ All in all, Squadron members travelled regularly by both sea and air across the 700 miles of water between East Malaysia and West Malaysia during the period of the Confrontation. During the course of 1966 the Indonesian Government began to show greater awareness of the worldwide lack of sympathy with its position. Discussions began with Malaysia in July and on 11 August, a peace treaty was signed in Bangkok. For the time being vigilance was maintained but the peace agreement held and it soon became possible to start withdrawing forces from Borneo.

On 17 September, the day before 10 Flight left Brunei for Malaysia, they were told that they were to move back to UK in November to rejoin 3rd Division on Salisbury Plain. This involved many problems, as the Flight personnel were in Malaysia and all the equipment, aircraft, small arms, etc, were in Brunei with 11 Flight. However, a tremendous amount of hard work on the part of the Flight Sergeant and his men ensured the stores were on the quay ready for shipment on literally the day before the Flight flew home from Singapore.

20 Flight’s experience was rather different. It was decided in June that the Flight would leave Hong Kong and re-establish itself as a Scout flight at Seremban in West Malaysia. The plan was that it would rotate with 2 Flight in East Malaysia. However, confrontation ended shortly after the Flight had arrived at Seremban and neither Scouts nor pilots were made available.

By October plans changed and the Flight repacked its stores and other chattels. Meanwhile, the last Auster 9, XK409, was flown from Kuching until October 1966 on surveillance duties, equipped with a listening device to detect radio transmissions. The remaining Austers in theatre were either sold to the Hong Kong Government for the Auxiliary Air Force, or scrapped by burning at Kuching. After a short period in limbo the Flight finally returned to Kai Tak equipped with Sioux.

Last Years in Malaysia

In November, SHQ left Labuan and joined 17 Division in Seremban, and continued to keep the name of the 656 Squadron alive, closely followed by 2 Flight. The redeployment back from Borneo enabled 4 Wing to have a get-together in Singapore of nearly all Flight and Air Troop/Platoon Commanders in December, where staffs and operators were able to exchange blows with ‘gay abandon.’

A very successful cocktail party was held in the ‘Old Folks Home’ (Senior Officers’ Mess) on the first evening of the Conference. At the start of the year the Flying Instructional Element was just beginning to find its feet, but by the end of 1966 it had managed to fly 1625 hours’ instruction and had passed sixty-five new pilots through its twenty-five hour theatre familiarization course. All pilots posted to FARELF, on arrival, first reported to their parent unit for a few days’ orientation and personal administration.

Then they moved to Kluang for the theatre familiarization course of twenty-five hours, during which they received not only a period of general refresher flying, but also learned how to tackle jungle clearings, local navigation, the weather and other Far East specialities. It was not a case of ‘forget what Wallop taught you’, but there were some advanced techniques which differed in detail from those in Europe. After this course, or sometimes before it if a suitable vacancy existed, each pilot attended the two-week course run by the RAF Jungle Survival School based at Changi. The newly joined pilot was then ready to rejoin his unit, having successfully been ‘passenger qualified.’

Major P.G.C. Child was SFI, WO2 W.A. Patrick, DFM and Staff Sergeant E. Ford, were the helicopter instructors, while WO1 Tapping looked after the Beavers at Seletar.

As it was responsible for the flying standards of all Army pilots in the Far East, stretching from Hong Kong in the north, Seria in Brunei, West Malaysia and Singapore – the same area that in north-west Europe would cover UK, the Low Countries and a considerable amount of BAOR – it was kept busy. In 1967 Air Vice-Marshal Christopher Foxley-Norris wrote,

‘The Borneo campaign was a classic example of the lesson that the side which uses air power most effectively to defeat the jungle will also defeat the enemy.’

It would have been more accurate to say the side which used air power most effectively in support of ground forces, would be the one which gained the upper hand. And it would certainly be fair to add that no squadron was more versatile and had greater experience of jungle warfare than 656 between 1944 and 1966. The ending of the Confrontation in 1967 made it possible to expand, ‘the exercise studies of the techniques of counter-revolutionary warfare,’ the practical result of which was a series of exercises in West Malaysia and included brief excursions to East Malaysia and Australia.

The Wing was able to study the employment of Army helicopters in the tactical troop lift, continuous airborne surveillance and gunship roles against a numerous and well-armed opposition. Also involved were both 7 and 11 Flights and the sub-units of 28 Commonwealth Brigade, a detachment of the Australian Army Aviation Regiment, 182 Recce Flight, which was equipped with three American Bell 47s and the four air sub-units of 3 Commando Brigade RM (Brunei, Dieppe and Kangaw Flights and 95 Locating Regiment Air Troop).

As regards HQ Army Aviation, 17 Division (656 Squadron) was now established in Rasah Camp, while 2 Flight had a ‘decent hangar’ in Paroi Camp. The year was a fruitful one in bringing Army Aviation to the notice of soldiers on the ground in other than an operational situation. The future of the HQ and accordingly of 656 Squadron was, however, undecided in view of im pending reductions in Britain’s military commitment to the Far East, which had been laid out in the Defence Review of 1966. In the light of the prevailing economic conditions the Government had resolved to cut down considerably on expenditure on overseas bases, a plan which was further reinforced by the Defence White Papers of the succeeding two years.

Despite this it can be said that the late 1960s were a pleasant time in which to serve in Malaysia and Singapore, as the economies of both were prospering and relations with Indonesia had been patched up into a state of mutual toleration. In May, the Commander Army Aviation and a team went into Thailand to look at the wreckage of Auster XK374, which was lost on 22 November 1961, with the pilot and observer (Captain P.H. Hills, RA and Captain D.J. O’Grady, RADC). They were accompanied by a platoon of Thai Border Patrol Police; the wreckage was duly inspected, photographed, and one or two pieces removed and brought back. It was discovered that the accident was caused by the failure of a union in the fuel pipe; the union had been incorrectly wire-locked.

The Gurkha Rifles Air Platoon in Borneo, 1966 (John Charteris)

At the end of September, Lieutenant Colonel R.J. Parker, MC, AAC, arrived fresh from Wallop ‘full of up-to-date knowledge’ to take over from Lieutenant Colonel P.E. Collins RA. His first function was to receive the Waghorn Trophy from Lieutenant Colonel Collins on 01 October, at the Army Aviation Parade, in which the HQ and 2 Flight formed a squad behind the Pipes and Drums of 17 Gurkha Signal Regiment and marched past the GOC, Major General A.G. Patterson, DSO, OBE, MC, while aircraft of 28 Commonwealth Infantry Brigade flew overhead.

The Waghorn Trophy, which was a large Royal Kukri mounted on a Malacca wood representation of the Malay Peninsula, was to commemorate the memory of Sergeant D.J.P. Waghorn RAMC, lost in Borneo in 1965. At the same time, the tip of the propeller from XK374 was returned to 2 Flight, duly polished and mounted.

At the end of January 1968, 11 Flight suffered a tragic loss when Scout XT625 had to make a forced landing near Grik after severe engine trouble which was caused by turbine blade failure. On impact the helicopter rolled over, trapping one of the three occupants, Corporal Christopher Galloway REME, who drowned. The pilot, Captain Chris Cross, and the other occupant escaped safely.

The year continued with various unit moves around the theatre, for example; the Royal Engineers Air Troop returned from Thailand, 7th Gurkha Air Platoon moved to Hong Kong, the Air Platoon of 3 Light Infantry spent ten months in Mauritius and in that period flew nearly 1500 hours, while 130 Flight RCT now had single aircraft detach ments in Nepal and Laos (for the use of the British Embassy in Vientiane, a role which would last for over seven years up until 1975, though XP821 was officially on charter to the Foreign Office from 1970 onwards) during the eight month non- monsoon period.

These movements, together with major exercises involving 2, 7, 11 and 14 Flights, kept HQ well occupied. They were delighted to see the new Brigadier Army Aviation, Denis Coyle, and his team in March. In three weeks they visited Singapore -Kluang -Terendak – Seremban – Penang -Thailand and Hong Kong. Apart from disseminating the Army Aviation gospel to all and sundry, the HQ organized Aviation Training Camps, through which all AAC Flights and all Air Troops and Platoons passed once a year, these were mounted with the capable assistance of 2 Flight.

The HQ expected only one further year in Seremban and hoped that the 656 Squadron title would be readopted elsewhere to continue to perpetuate its proud record. In March, 2 Flight gave a display of airborne GPMG night-firing to an audience of senior officers. The target area was illuminated by slow-falling flares, dropped from a Beaver provided by 130 Flight. As the aircraft were blacked out, and, they were told, impossible to see, the effect of 600 tracer rounds fired on to a small target with some accuracy was startling to behold. In mid-1968 the flights were located as follows:

Kluang 11 Flight,

Seremban (Paroi) 2 Flight,

Sembawang (Singapore) 14 Flight

Terendak (Malacca) 7 Flight.

All those Flights had six Scouts.

Sioux units were:

10 Gurkha Rifles Air Platoon (Penang),

RE Air Troop (Khota Tingii),

6 Gurkha Rifles Air Platoon (Kluang),

Life Guards Air Squadron (Changi),

Commando Brigade Air Squadron Royal Marines (Sembawang),

20 Flight AAC in Hong Kong

2 Gurkha Rifles Air Platoon in Brunei.

The Air Platoons and Troops had three Sioux each, the Life Guards six, 20 Flight ten and the Commando Brigade about sixteen.

There was also, of course, 130 Flight at Changi with six Beavers. Captain John Charteris was with the Air Platoon at Penang, which was working with the SAS preventing infiltration from Thailand and where Shack the Gibbon disgraced himself by performing his party piece at a Mess Function. All went well at first, as he rotated gently beneath the roof fan, but did not improve as the guests in their finest begin to feel a light but pungent shower descending on their heads.

An additional change was the termination of the RAF’s presence at Labuan in the middle of June, which was a source of regret to many. In July, 2 Flight sent a couple of pilots and aircraft on annual AOP shooting with 14 Light Regiment RA, closely followed by deck landing practice on the LSL Sir Galahad prior to the eagerly awaited Australia deployment.

Army Pilots could never resist an opportunity to add a carrier landing to their log books; this is HMS Albion

Exercise Coral Sands, which took place on the east coast of Australia, was undoubtedly the main event of the year. Having departed from Singapore on board LSL Sir Galahadthe Flight (plus two aircraft and pilots from 7 Flight) spent ten days ‘soaking up the sun, food and alcohol’ whilst cruising past Indonesia, Bali, Timor and finally the Great Barrier Reef, to their destination at Shoalwater Bay. After ‘count less games of cards, darts and “uckers” played on the high seas’, they were relieved to get down to some interesting flying in a new country. The training area was certainly no paradise for those being exercised.

Both hills and plains were amply covered with gum trees and dry grass and very prone to bush fires at that time of the year. Fortunately, they were based on the LSL for the whole period and enjoyed the good food, air conditioning and hot and cold running water provided on board. Flights to the assault ship HMS Intrepid and the Commando carrier HMS Albion were commonplace for all pilots and two were fortunate enough to land on board the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes, which was at the time cruising some 30 to 40 miles out to sea. However, as soon as they had landed their passengers they were told to hover alongside whilst naval fighter aircraft took off and landed.

Pilots WO2 ‘Red’ Meaton, Sgt Barrie Davies and SSgt Tony Horsey, after taking off from HMS Albion and landing at Sibu in Sarawak, en route to Brunei, January 1964

Some forty-five minutes later they were granted permission to land again to rest their weary limbs. After the exercise ended the Flight was allowed to ‘go ashore,’ taking with them four aircraft and twelve members of the Flight. The aim was to fly north and meet the ship at Townsville and whilst there to organize suitable female company for a proposed party on board,

‘The first night was spent in a small sugar port of Mackay where everyone found accommodation with the assistance of friendly beer-drinking taxi drivers. The pilots got on so well with their taxi driver that they ended up being shown round a sugar refinery at 11.30 pm on a Sunday.’

Townsville was reached by noon on the second day, where they eventually persuaded the RAAF to put them up for two nights, money at this stage running rather short. They soon made their way into the city of Townsville, population 35,000, and ‘having purchased the right number of koala bears and boomerangs’ set about the serious business of finding willing company for the impending party,

‘To say their mission was 100 per cent successful was perhaps not quite true, however, the wardroom rang with the sound of shuffling feet and elbow jostling made by military and ship’s officers eager to get to know the six air hostesses and ten university students provided by the apprehensive pilots.’

Most felt it was a good thing when the Flight finally set sail for Singapore, knowing that they had a clear nine days to recover from their Australian entertainment. At the end of the year the Flight had one aircraft on detachment at Grik near Butterworth in North Malaya in support of troops training there. One pilot reported having flown thirty-four hours in seven days, which the Flight assumed must be a record. Despite technical problems with its Scouts, 11 Flight managed to continue its service for the South of Malaya which was instituted in 1967.

Since then a total of forty-eight serious medical cases were flown to the British Military Hospital in Singapore. Flight personnel considered this to be a really worthwhile task which kept everyone on their toes and provided an added incentive to maintain night flying training. The Flying Instructional Element reported ‘rather a lean year in many ways,’

‘Not only had both the Sioux and the Scout suffered from periods of debility, but the Element had also been presiding over a contraction of our once large empire. Hong Kong, Thailand and Mauritius all left our mandate. On the other hand the amount of paperwork passing between Kluang and Middle Wallop increased alarmingly.’

Lieutenant Colonel R.J. Parker departed after a year, on elevation to 1 Wing in BAOR. His relief was Lieutenant Colonel Michael Hickey, who returned to 656 Squadron, having served from 1953-55 in 1907 Light Liaison Flight.