Hong Kong

Description of Operations QE Catches Fire

Security Operations Illegal Immigrant Ops

“Origins of Army Aviation in Hong Kong”

1903 Flight had served In Hong Kong from 1949 until going to Korea in 1951; 1900 AOP Flight was sent out in 1953, equipped with Austers Mk 6 and Mk 7 and was retitled 20 Independent Recce Flight in 1957.

Auster AOP9 WZ731 overflies Aberdeen harbour in Hong Kong

Auster AOP9 WZ731 overflies Aberdeen harbour in Hong Kong

Typical duties included taking part in range shoots, dropping supplies or mail to infantry patrols, recce flights along the border, providing ‘targets’ for ship and anti-aircraft tracking radars, tracking practice torpedoes, assisting the colony police in public order duties and searching for smugglers, illicit stills or poppy cultivations, plus such one offs as counting the number of sharks and manta rays in coastal waters and flying a Public Works Department surveyor on aerial inspections of possible sites for reservoirs and roads. It was customary for 656 Squadron to provide the pilots for its independent Hong Kong cousin, usually towards the end of their Malayan tours, though normally the Flight Commander came straight from the UK.

Typhoon Wanda wreaked havoc at Shatin in 1962, destroying all the Austers and causing the Flight to move back to RAF Kai Tak. Tragically, three of the Flight’s pilots, Flight Commander, Major Peter Richardson, Captain Ian Horsley-Currie and Captain Ian Stevens were killed on 25 July 1963, when the Auster 9, XN420, crashed into a hillside. A later Board of Enquiry concluded that the probable cause had been a downdraft or sudden turbulence.

The first Sioux arrived for service with newly formed Air Troop 49 Light Regiment RA in 1965. The remaining Austers were sold to the Royal Hong Kong Auxiliary Air Force in 1966. In the 1960s and 1970s Hong Kong was thriving commercially, business and associated building works were booming. The main security concern was stemming the flow of illegal immigrants across the Chinese border, while the police were greatly exercised by the desire to reduce the level of smuggling.

Captain John Charteris was OC 3rd Gurkha Air Platoon at Sek Kong in 1966-67 and recalled such incidents as taking off with two passengers but landing with three owing to a birth in mid-air, looking into China from 10,000 feet and the mass flight of RN Wessex from HMS Bulwark which got a much closer look in February 1967. Ignoring local advice, a large formation flew by mistake into Chinese airspace before making a rapid about turn and caused, ‘an almighty row.’

The Hong Kong Aviation Squadron had been formed in February 1969, on an interim basis, at Sek Kong camp in the New Territories and was the result of the amalgamation of the four aviation units in the colony. These were 20 Flight, who moved from RAF Kai Tak, to join the Air Platoons of 6th and 7th Gurkha Rifles and the Air Troop of 25 Light Regiment Royal Artillery, all of whom were already operating from Sek Kong. The Interim Squadron was officially established and titled as 656 Squadron in mid October. In deference to Army Aviation 17 Division this was not assumed until the end of December 1969, when the final disbandment was completed in Malaysia.

Up to the end of 1969 the Squadron was equipped with twelve Sioux helicopters, which had proven ideal for the Hong Kong terrain. Scout helicopters arrived during January 1970 by ship from various flights in the process of disbandment in Malaysia. For example, all the 7 Flight Scouts went to Hong Kong from Terendak in the LSL Sir Galahad in January 1970, along with the families, pets, cars and also the 656 silver inside one of the Scouts.

The Scouts and the silver were handed over to Major Peter Ralph, the new OC 656 Squadron, by Major Spencer Holtom at Sek Kong on 1 February 1970. During February some Sioux were returned to Europe and the Squadron’s establishment was fixed as two flights of eight helicopters, one of Sioux and the other of Scout. Two reserve helicopters, one of each type, were also held. Second line repairs and major servicing were carried out by a civil aircraft engineering firm located in Kowloon. The Squadron was under the administrative command of 48 Gurkha Infantry Brigade as a HQ Land Force Unit. It also supported 51 Brigade, the RN, the RAF and the Royal Hong Kong Police. It was noted, ‘Therefore our masters are currently one general, three brigadiers and one colonel in Singapore.

“Description of Operations”

Peter Ralph wrote an article for the AAC Newsletter in which he described operations in Hong Kong,

‘The flying conditions vary with the season but are always interesting. The often strong winds make operations in the mountainous areas reminiscent of North Wales in the later stages of pilot training, except that it is a lot hotter and humid. In Kowloon and Hong Kong the air traffic density is similar to the circuit at Wallop. It is not uncommon to see four or five helicopters of all three services trying to cross the runway of the civil airport with a stream of Boeing 707s landing or taking off.

As well as the Squadron’s aircraft, there were also helicopters from visiting RN ships, Whirlwind Mk 10s of No 28 Squadron RAF and lastly the Royal Hong Kong Auxiliary Air Force with Alouette IIIs and Auster Mk 9s. Night flying in the urban areas is an awe-inspiring sight for which tourists would pay a fortune to see. The lights are many and colourful, making London’s Leicester Square look like a blackout zone. Landing points are varied, ranging from a jetty surrounded by Chinese territorial waters, to roof tops in the centre of Kowloon, to observation posts a few hundred yards from the Chinese border with Guangdong Province, from whence comes “provocations” and “shows of force” by the million strong People’s Liberation Army.’

The first official visitor to the new Squadron in 1970 was particularly welcome, the Director of Army Aviation, Brigadier Denis Coyle. Even more welcome perhaps, was the independence granted to Hong Kong in April 1970 – at least as regards the military chain of com mand. As a result the Squadron ceased to be part of 4 Wing and ‘will deal direct with our masters in Whitehall.’ A full report was made on its first year of existence,

‘This year has seen a continuing round of exercises during which the Squadron was fully deployed on five and had one flight deployed on a further nine. By far the most interesting were the two amphibious exercises during which operations were partially off the assault ships Fearless and Intrepid. Operating from the crowded flight deck of these ships – in company with four Westland Wessex HU5 – made a pleasant change from the airstrip at Sek Kong.

All pilots are now deck qualified, some by night as well, and a sound alliance has been established with 845 and 847 Royal Naval Air Squadrons. Our other exercises have been more conventional, operating over the hilly and rugged terrain of the New Territories. The helicopter has proved its versatility in this theatre and has in every way justified aviation as a supporting arm. Apart from the more routine aviation tasks we do photographic reconnaissance with conventional and Polaroid cameras, sky shouting on internal security situations, night illumination with flares and searchlights, and water operations with flotation gear.

From a flight safety and operational aspect there has been a requirement to fit some Sioux with flotation gear. A protracted trial was completed and we now have two Sioux equipped with floats. Landing on and off water opens a new area of operation which has proved useful and is interesting for the pilots. Engine off landings are now patterned by QHI in nautical terms “All clear below, no boats,” or “Midships, mind the yaw,” or “Oops I told you it was a heavy landing if it stays green,” were commonplace during the early stages of conversion. It is comforting, though, to be flying one of the “rubber jobs” when over the sea on a two-hour photographic mission and we have used them in earnest once for a sea rescue.

Our other major acquisition has been a Nite-Sun Searchlight specially modified for the Sioux. This light is by far the best we have seen and its performance in Hong Kong has won itself nothing but praise from pilots and observers on the ground. This light can be remote controlled in four planes from within the cockpit and produces an intense white beam, effective from heights up to five thousand feet above the ground. Pilot reconnaissance is as good as in daylight when at two thousand feet. An observer on the ground can read the evening newspaper with the light four thousand feet above him. It was the biggest single factor in discovering the clandestine landing of troops on Exercise Sea Horse. We understand that eventually we are to be given two on the completion of a confirmatory trial in the United Kingdom. Life is very good in Hong Kong. The work is interesting and entertainment is full and varied.’

While the Squadron was not engaged in the dangerous operational flying that had been its bread and butter for nearly a quarter of a century, there were still challenges to be faced,

‘The general flying was in some ways quite challenging as we had to contend with hot and high conditions and the various wind affects in and around the many high hills and rocky outcrops. In addition to this the typhoon season produced its own batch of violent storms and strong winds/gales. Some of the HLS locations were more challenging than normal – for instance, Victoria Barracks on Hong Kong Island had a landing platform built into the side of a steep hill and which jutted out towards the sea. There was only one approach which was directly towards the hillside and thus there was no chance of an overshoot! If the approach had been downwind then the take-off was best accomplished by a transition backwards with a controlled right pedal turn into wind.

We (the Scout pilots) did quite a lot of troop lifting which worked very well. The requirement was usually to move something like a company of infantry a short distance from the base of a steep hill to some point further up which, in the heat, would be both difficult and tiring to climb, taking many hours with the troops exhausted at the end. It took us only a matter of a few minutes with each load to cover some really difficult terrain.

Sometimes the RAF with Whirlwinds would work with us and it was weird to see the much bigger Whirlwind helicopters just lifting two or three troops whilst the Scouts were taking four or five soldiers. The downside of flying in Hong Kong and the New Territories was that it is only a small area (about forty miles east-west and thirty miles north-south). The area became so familiar that often there was no need for reference to a map to get to a place and navigation was limited to very short distances indeed.’

“Cunard Liner Queen Elizabeth catches fire”

One of the most dramatic events of the Squadron’s time in Hong Kong occurred on 09 January 1972, when the former Cunard liner Queen Elizabeth (which had been renamed Seawise University) caught fire in Victoria Harbour.

The OC was actually on board the Star Ferry in the harbour when he contacted the duty pilot and ordered him to get airborne as soon as possible. Within fifteen minutes Staff Sergeant Cox and Sergeant Simpson were overhead in a Sioux, watching the smoke billowing upwards to a height of 1500 feet. An Alouette of the Royal Hong Kong Auxiliary Air Force was already darting in and out over the decks checking to see if anyone remained on board.

Back at Sek Kong, three Scouts were made ready with ladders and ropes in case rescue operations were necessary. In the event they were not needed as all those on board had jumped over the side and had been picked up by sampans standing alongside. At 1200 the next day, Sergeant Sharpe reported that the grand old Cunarder had rolled over to starboard but with the Union Jack and Red Ensign still flying defiantly. The ship was completely destroyed by the conflagration and the water sprayed on her by fireboats caused the burnt wreck to capsize and sink in the harbour’s shallow water.

There was some speculation that the fire was not accidental, as the ship’s owner, CY Tung, had bought the vessel for $3.5 million and insured it for $8 million.

“Internal Security Operations”

By this time the Squadron was providing support to all Hong Kong units exercising throughout the Far East and for the equivalent of a division engaged in limited war training in the Colony. It worked in close association with No 28 Squadron, which was now equipped with Westland Wessex HC Mk2s. They combined to form the Joint Helicopter Force and used a common command net, procedures and tasking cell. It was noted in the AAC Newsletter that,

‘Our Internal Security operations range from the normal and well known tasks, such as the reinforcement of police stations by heliborne troops and night surveillance etc. to Vietnam type helicopter assaults, complete with pathfinders and gunships. We practise these regularly by day and night, including live fire-plans from guns and mortars which have been initially airlifted into their firing positions.

The night ops are particularly interesting with flare illumination for two pathfinder Scouts engaged in roping down to the landing point, and the securing troops being provided by another pair of Scout/Sioux stationed above them. During Exercise Eastern Triangle we flew 450 hours, including fifty at night on ten aircraft in ten days. Our friends in the RAF flew just under 400 hours on eight Wessex in the same period.’

Early in 1975, Major David Swan was posted to Hong Kong to replace Lieutenant Colonel Greville Edgecombe in command. Following a Scout refresher course at Middle Wallop, he arrived in Hong Kong in May, just before the Queen, who would be making her first State Visit to the Colony. His official title was not only CO 656 Squadron AAC, but also Commander Aviation Far East, as there were Squadron detachments in Brunei (C Flight) and Singapore (11 ANZUK Flight).

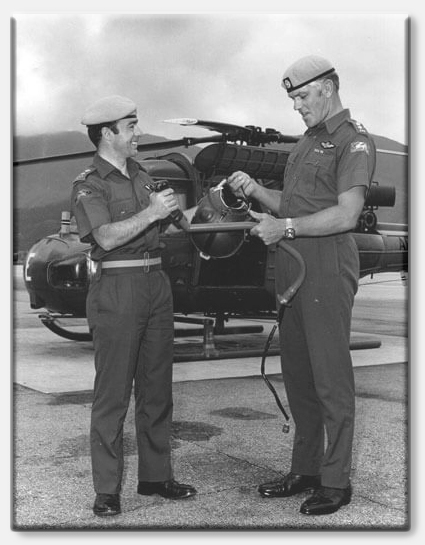

In May 1975 Lt Col David Swan assumed command from Lt Col Greville Edgecombe

In May 1975 Lt Col David Swan assumed command from Lt Col Greville Edgecombe

11 Flight closed down in September 1975, so there was only time for him to make one trip to Singapore. The Squadron itself was under the command of 48 Gurkha Infantry Brigade at Sek Kong.

C Flight, at Seria in Brunei, would remain equipped with three Sioux and manned on a six month rotational basis from Hong Kong, later extended to one year. The personnel were looked after by the resident Gurkha Battalion, while the Flight was based in a small hangar close to the beach. As well as carrying out all normal aviation tasks, with observers supplied by the Brigade of Gurkhas, the Flight also provided support to all Hong Kong units engaged in jungle training in Brunei. Spencer Holtom remembers,

‘David Swan was keen to have a spare Sioux as a backup for Brunei and XT546 had just had a Major overhaul, I managed to get it on a Hercules from Tengah and it was delivered to Kai Tak, the other three Sioux I had with 11 Flight in Singapore were sold to the RMAF and taken off to Kuala Lumpur. When I got to Sek Kong in November 1975, I was the only person current on Sioux and it was my job to keep XT546 flying a few hours a month to keep it exercised, all the other aircraft were Gazelles by then; in the event it was never needed in Brunei.

It became my personal helicopter and I used to take chums round the colony on photo trips – also, I used it to do a photographic survey of the Royal Hong Kong Golf Club prior to realignment of the Old Course, the Sioux was a perfect platform for this. Happy days!’

“Chinese Border Flights checking for Illegal Immigrants”

One of the Squadron’s major tasks in Hong Kong during this period was carrying out patrols along the Chinese border, which were predominantly dawn sorties, searching for and intercepting illegal immigrants seeking their fortune in Hong Kong.

Resupply of stores to the hill top radar site at Tai Mo Shan

Resupply of stores to the hill top radar site at Tai Mo Shan

The aircraft usually carried three armed Gurkha soldiers whose role was to disembark and attempt to catch anyone spotted by the aircrew. This was not always successful, as the Chinese became very adept at hiding in the undergrowth, crossing the water at night using all sorts of inflatable devices and hiding up during the day. Once they reached the built-up areas they would be virtually impossible to trace by the police.

In November 1975, Sergeant Timothy Smith, flying a Scout, had to make a forced landing in the sea off the Tolo Peninsula. Both the pilot and his passenger were given assistance by a local fisherman, Mr So Yat, who took them to a nearby Army camp in his boat. He later received a framed Commendation and a mounted Squadron Crest for his efforts.

“Transition from the Scout to the Gazelle”

David Swan describes the transition from the by now well-loved Scout to the Westland Gazelle AH1, which was manufactured at Yeovil, following the Anglo-French helicopter agreement, which also included the Puma and the Lynx. It was developed from the original Sud Aviation SA340,

‘The changeover from Scouts to Gazelles required some major reorganization within the Squadron. The pilots had to return to Middle Wallop for conversion flying courses. In order to maintain our aviation support to the colony, half went at a time, leaving the others to fly the Scouts until the Gazelles were up and running.

The REME technicians had to learn about the innards of the new arrival. However, some already had Gazelle experience, which was a bonus. The first three Gazelles arrived at Kai Tak inside a Short Belfast C Mk 1 freighter on 26 November 1975 and the next day the same aircraft took three of our Scouts back to UK. After an overnight stop and a quick check over at Kai Tak, the Gazelles were given clearance for the short formation flight to Sek Kong where we were welcomed by various dignitaries and the Squadron families. The aircraft were then impounded by the LAD for acceptance servicing and modifications. The remaining three Gazelles arrived in Hong Kong and the last three Scouts departed the same way on 16/17 December.’

Exercise Swan Around II was a proving exercise in support of 48 Gurkha Brigade, and Exercise Frozen Gleam, where the aircraft were used in support of units for the first time. The Squadron was declared operational again on 19 January 1976. As David noted,

‘As the weather warmed up and the south-west monsoon rains arrived, there was some trouble with separation and holing of the rotor blade leading edges and three sets of blades had to be changed in a short space of time. However, the aircraft proved reliable and popular with passengers and the “extras” fitted (rubber mats and freight floors) kept damage to the minimum.

We had some concerns about the possibility of rifles making holes in the canopy but there were no such incidents, mainly through careful training and briefing of passengers and troops. It was amazing how many visitors “required” an airborne familiarization trip around the island and the New Territories.’

Another of the Squadron’s activities was the further development of air mobile type operations, deploying Gurkha infantry around the colony in conjunction with the RAF Wessex HC2s. They practised this whenever the time and opportunities arose and Standing Operational Procedures (SOPs) were written. The normal drill was that the Gazelles would carry out the recces and the RAF the troop lifts. These mutual activities attracted the attention of the Joint Warfare Establishment in UK, whose team paid a visit to Hong Kong and were ‘quite complimentary about our humble efforts.’ One Gazelle was fitted with a Nite Sun searchlight and the capability of installing a Skyshout loudspeaker was also provided.

Later in 1976, Sergeants I.D. Johnstone and D. Clark were awarded Director Army Air Corps commendations for carrying out a medical evacuation in difficult conditions at night. In December the Squadron passed from the command of Land Forces Hong Kong to the operational control of the Gurkha Field Force.

David Swan’s tour came to an end in June 1977 and at the same time the Squadron’s presence in Hong Kong and Brunei also drew to a close. The OC designate was Major Dick Whidborne, but his time in command of the Squadron was brief indeed, as by the start of July, the unit was retitled 11 Flight. The introduction of the armed Lynx to the AAC in Europe allowed representations to be made to bring Scouts back to Hong Kong. This was agreed and the Flight was equipped with six Scouts in Hong Kong, three in Brunei and two Sioux in Hong Kong. The Director Army Air Corps, Major General Tony Ward-Booth, then decided that, ‘the unit in Hong Kong was far too important to be a flight and had to be a squadron.’

The Squadron performs a farewell fly past at Sek Kong for departing OC Major David Swan

The Squadron performs a farewell fly past at Sek Kong for departing OC Major David Swan

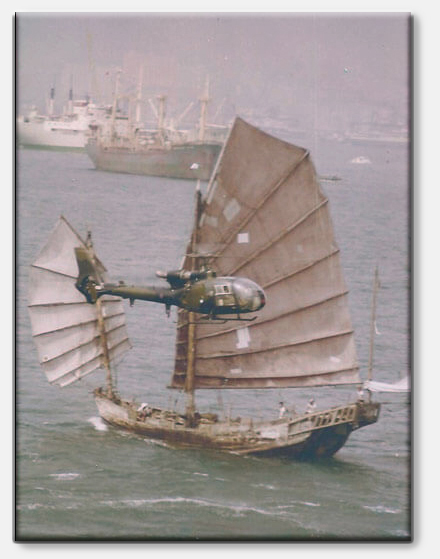

A Squadron Gazelle with an iconic Chinese junk in Hong Kong

A Squadron Gazelle with an iconic Chinese junk in Hong Kong

On its disbandment on 01 August 1978, 11 Flight flew a formation of a Gazelle, two Scouts and two Sioux over Victoria Harbour. The Hong Kong unit was again retitled as 660 Squadron which became the resident AAC unit at Sek Kong, equipped with Scouts and remained there until March 1994 (though it should be noted for the record that Major Whidborne flew what was believed to be the last Sioux, XT546, at the RAF Sek Kong Airshow on 17 November 1978).

He has many vivid memories of his time in Hong Kong,

‘The primary role of the Squadron was to patrol the border between Hong Kong and Guangdong (Canton) province of China. There were daily attempts by mainland Chinese to enter Hong Kong illegally in a quest to reach “base” in Kowloon, where they could eventually be assimilated into the local population. Many attempts involved a night swim across a narrow stretch of water in the north-east of the colony.

A dawn helicopter patrol might find “IIs” (Illegal Immigrants) hiding in the area in preparation for a further covert dash for the south. One morning I was on patrol with my Air Gunner observer and a Gurkha major in the back of the Scout. We searched a small island, and finding nothing continued towards another search area. The Gurkha major tapped me on the shoulder and gave me a “thumbs up” sign. Rather than an affirmation that all was OK, I was later to learn that this indicated the presence of “enemy” and so we returned to the little island to find five “IIs” who had emerged from under the bush in which they had been hiding. The Gurkha major had spotted them, but I had not!

They were rounded up and handed over to the Royal Hong Kong Police (RHKP) at their Fanling holding centre. In most case they were returned to mainland China where they met several differing fates. If they were first offenders they were shipped well inland or returned to their villages. Persistent offenders were sent further away or imprisoned.

Fleeing “IIs” were often hounded by dogs and / or shot by border guards. One very sad incident involved an “II” who had gained the HK shore but then hung himself from a tree having lost the rest of his family through drowning in the water crossing. During this time the colony was the chosen haven for fleeing Vietnamese “boat people”. They arrived in a variety of vessels and attempted to smuggle themselves ashore. The squadron was often tasked to photograph such incidents when the boat people had been discovered. At Tai O I photographed a sampan crowded with refugees, who were only able to stand up because of the density of their crowd, whilst the sampan was close to sinking. They had managed to float across the Yellow River estuary.

One significant incident involved the Huey Fong, a rust bucket freighter crowded with boat people in the most unimaginable squalor. The ship, from Vietnam, was halted by the Royal Navy on the international boundary and lay there at anchor for several days. The RAF Wessex helicopters ferried food and water and other supplies whilst a solution to the refugees’ plight was sought. The squadron Scouts carried out surveillance and photography sorties of this pitiful scene. Eventually the refugees came ashore and were accommodated in huts on part of the airfield at Sek Kong, which was of course the squadron base.’

The recovery of Gazelle XX409 from Hong Kong harbour in February 1977 by HMS Wasperton

The recovery of Gazelle XX409 from Hong Kong harbour in February 1977 by HMS Wasperton

Typhoon Hope

Pilots from 656 Squadron Farnborough returned to Hong Kong on rotation to help out with the increased Illegal Immigrant influx. This pilot rotation carried on until the Squadron’s imminent deployment OP AGILA. During one of the rotations, Sgt CK and S/Sgt Scotting were caught up in a Typhoon called “Hope”. Luckily, the 12 bells had been called and all aircraft were hangered and pilots limited to their respective messes.

Both Sgt Mike CK and S/Sgt Dave Scotting had lucky escapes while residing in the SNCO’s Mess. Mike CK explains,

Both Dave and I watched in astonishment from our window as bits of village flew down the runway at Sek Kong, The wind was horrendous and you could feel the increase in pressure in your ears. I realised I had left a book in my room and duly went upstairs to get it. I found it extremely difficult to open my room door but when I did manage and walked in all I saw was the large bedroom window bowing towards me. I dived out of the room and the door slammed behind me. At the same time the bedroom window exploded shattering glass all over my room. It seems that I had unwittingly allowed the pressure which had built up in my room with the door closed to escape and as there was a much greater pressure outside the window the inevitable happened.

The road outside the mess toward the Hangers.

The road outside the mess toward the Hangers.

When the eye of the storm was overhead, which last for about 30 minutes, the Gurkhas dug out the drainage ditches and we took a look at the damage before retreating again into the mess for the second part of the typhoon with the wind coming this time from the opposite direction.

Sgt CK inspecting 660 Squadron Gate Guard. It was ripped off its plinth and damaged beyond repair.

Sgt CK inspecting 660 Squadron Gate Guard. It was ripped off its plinth and damaged beyond repair.

Dave Scotting and myself where feeling a bit peckish as it had been about 6 hours since we had last eaten and the Typhoon was still raging. We went down to the Dinning room and opened the doors. I obviously didn’t learn from the first time because the same thing happened and the mess dinning room windows were an awful lot bigger.

We closed the doors and waited for the pressure to subside. Dave and I then rolled up the large carpet which was now covered in glass.

Sgt’s Mess Dining room minus windows, post typhoon. SSgt Scotting in the back ground.

Sgt’s Mess Dining room minus windows, post typhoon. SSgt Scotting in the back ground.

7 Flight returned to the Far East in 1994, to be based at Seria in Brunei, replacing the Scouts of C Flight 660 Squadron. It is still serving there and continues to fly the Bell 212. With the retitling of squadrons, which paid little respect to military heritage, 656 Squadron’s time in the Far East finally – at least in this era – came to an end.