Op Agila 1979 – 1980

OP AgilaConduct of OperationsSummary of OperationsOn 15 November 1979, the Squadron was given five weeks’ notice to be ready to depart for Rhodesia, where elections were to be held which it was hoped would bring to an end a dispute which had begun on 11 November 1965, when the government of the British colony of Southern Rhodesia, under its Prime Minister, Ian Smith, issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI).

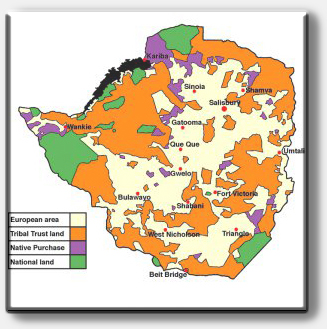

Land Distribution 1965

Attempts to reach a compromise by personal meetings, held first on board the cruiser HMS Tiger and then the assault ship HMS Fearless, between the British Prime Minister, Harold Wilson and Ian Smith failed to reach an agreement. Trade sanctions were imposed and a naval blockade was implemented. Rhodesia was declared a republic in March 1970.

Then, in 1972, a guerrilla campaign was begun with scattered attacks on isolated white-owned farms by the military wings of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), led by Robert Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo respectively, which wished to bring white rule of the country to an end. Mugabe’s army was ZANLA (Zimbabwe National Liberation Army) which was largely drawn from the Mashona tribe and received considerable support from China, while Nkomo’s was ZIPRA (Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army), which was mostly Matabele and obtained weapons and training from Cuba and the USSR. Both peoples were traditionally enemies.

Initially, the activities of ZANLA and ZIPRA were contained by the Rhodesian Security Forces (RSF), but it developed into a very nasty conflict with bloody deeds on both sides. However, the situation changed dramatically after the end of Portuguese colonial rule in Mozambique in 1975. All attempts made by Smith, Nkomo and Mugabe to broker an honourable peace that would guarantee the rights of the white minority failed. In September 1976 Smith accepted the principle of black majority rule within two years.

By 1978-79, the ‘Bush War’ had become a contest between the guerrilla warfare placing ever increasing pressure on the Rhodesian government and civil population and the Rhodesian Government’s strategy of trying to hold off the militants until external recognition for a compromise political settlement with moderate black leaders could be secured. Elections were held in April 1979. The United African National Council party won a majority in this election, and its leader, Abel Muzorewa, a United Methodist Church bishop, became the country’s Prime Minister on 01 June 1979. The country’s name was changed to Zimbabwe Rhodesia.

While the 1979 election was non-racial and democratic, it did not include ZANU and ZAPU. In spite of offers from Ian Smith, the latter parties declined to participate. Bishop Muzorewa’s government did not receive international recognition. The Bush War continued unabated and sanctions were not lifted. The international community refused to accept the validity of any agreement which did not incorporate the ZANU and ZAPU.

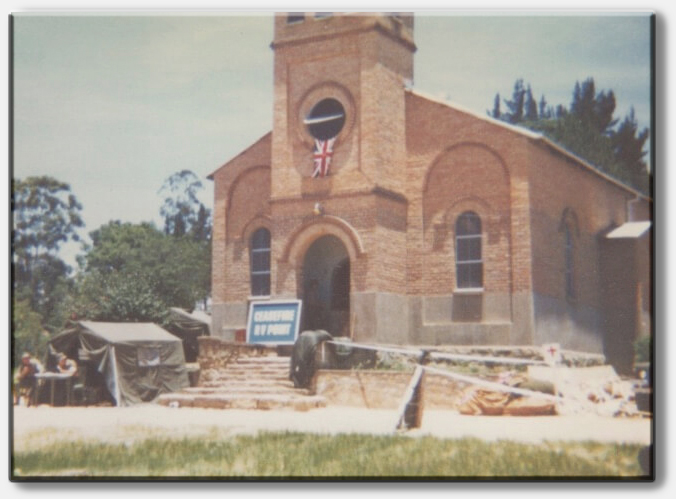

The British Government (then led by the recently elected Margaret Thatcher) issued invitations to all parties to attend a peace conference at Lancaster House, in late 1979,which resulted in the Lancaster House Agreement. UDI ended, and Rhodesia reverted to the status of a British colony under a new Governor, Lord Christopher Soames.

Op AGILA

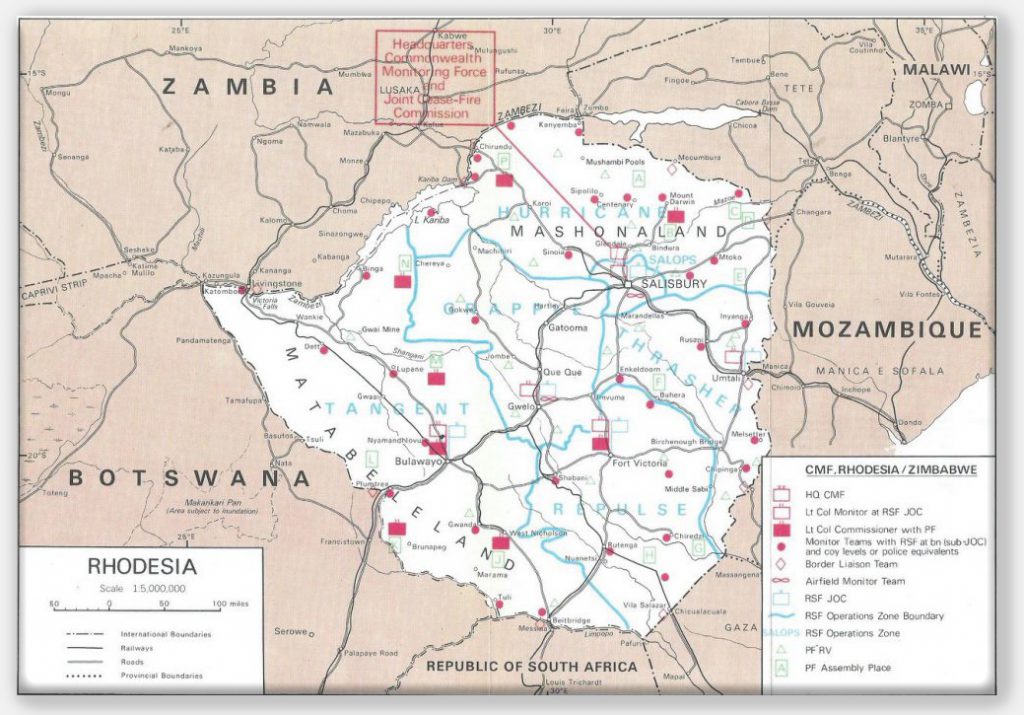

Some 1500 British and Commonwealth troops (drawn from Australia, New Zealand, Fiji and Kenya) were sent to monitor and supervise the ceasefire between the Rhodesian Security Forces (RSF) and the guerrillas – known collectively as the Popular Front (PF) – with the prospect of an internationally supervized general election in early 1980.

This was named Operation Agila and the collective name of the troops deployed was the Commonwealth Monitoring Group (CMG).

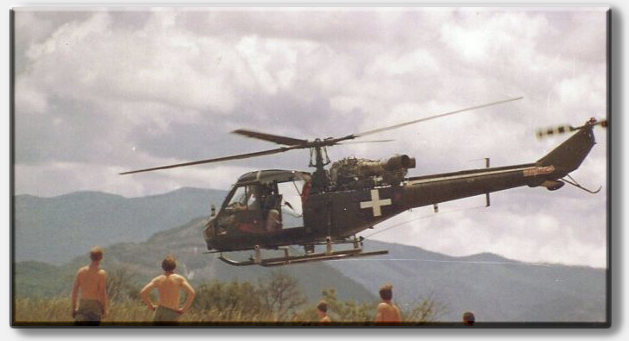

Before deploying, the Squadron used its five weeks of grace (while fourteen deployment timetables were considered and re-written) to study the military and political background; to brief themselves on the climate and terrain; to discuss the technical problems associated with hot and high operations; to study detailed maps, preparing the aircraft; painting them white (which washed off in heavy rain); covering them with DAYGLO (and removing it again) and finally adding large white crosses to fuselages and tail fin; then collecting special stores: armour (which in the event was not used); infra-red shields (which were); survival packs, sand filters and SARBE beacons.

First Gazelles arrive Theatre

The initial requirement had been for a detachment of three Gazelles, which were placed on forty eight hours’ notice, with a further detachment at seventy-two hours’ notice. Within three days of arriving in theatre it was accepted that another six Scouts should also be sent out (which the Squadron had known all along would be required).

The first elements of the Squadron (and also No 230 Squadron RAF) left Brize Norton on 20 and 21 December 1979, in RAF VC10s and C-130 Hercules, as well as enormous USAF C-5 Starlifters and Galaxys, routing via a combination of Cyprus, Egypt and Kenya. It was noted that a single Galaxy could transport three Gazelles, three Pumas and 20,000 lbs of freight and still have room for forty passengers.

Squadron fully formed in Theatre

Within two weeks all eighty personnel, six Scouts and six Gazelles had arrived, under the command of Major Stephen Nathan. Maintenance was the responsibility of a detachment from 70 Aircraft Workshop. The Gazelles were based in the capital, Salisbury, with the HQ Monitoring Force and Government House sharing a hangar with the RAF as well as Rhodesian Bell UH-1Ds and Alouette IIIs (remarkably and somewhat worryingly, all the Rhodesian helicopters had twin waist guns which were left unguarded, loaded with ammunition and belt feeds); while the Scouts were in Gwelo, at the Rhodesian Air Force base, Thornhill.

The Gazelle crews covered the north and east of the country, which was twice the size of the UK, while the Scouts looked after the west and south, which was the location of many of the assembly points for ZANLA and ZIPRA guerrillas coming in from the bush. Operations began on Christmas Day with two aircraft being tasked to fly Brigadier John Learmont, the Deputy Force Commander and some of his staff to Umtali. Brigade HQ was situated in the Morgan High School, Salisbury, which possessed playing fields in which helicopters could land.

The initial period was a very tense time; the weather was atrocious as it was the wet season, and moreover, no one knew how the guerrillas would react and if a self-defensive force would have to be applied. The ceasefire came into effect at 0001 hours on 29 December. Some thirty-nine Rendezvous Points (RV) and sixteen Assembly Places (AP) were set up across the country. During a ceasefire period of seven days, members of the ZIPRA and ZANLA were guaranteed unhindered movement through the RVs and into the APs. Here, their names were recorded, together with details of the weapons they carried. They were also provided with food, clothing and bedding. Considerably more people arrived than had been expected, some 22,000.

Gazelle ops in the North.

The heavily-armed and ill-disciplined fighters tended to carry their weapons loaded, cocked and with safety catches off, which did nothing to simplify the task. The scale of the task created something of a logistical nightmare, which the AAC and RAF helicopters did their best to alleviate with many resupply missions. The OC later commented,

‘The guerrillas were never entirely relaxed when we were in the air; at all locations they covered our approach with at least one AA machine gun and, whilst the aircraft were on the ground, with small arms and RPG-7… in the first few days we gave away hundreds of cigarettes… and showed many of them around the helicopters in order to create some kind of trust. What else can you do when armed with a 9mm pistol and a white flying helmet, surrounded by hundreds of rifles and rockets?’

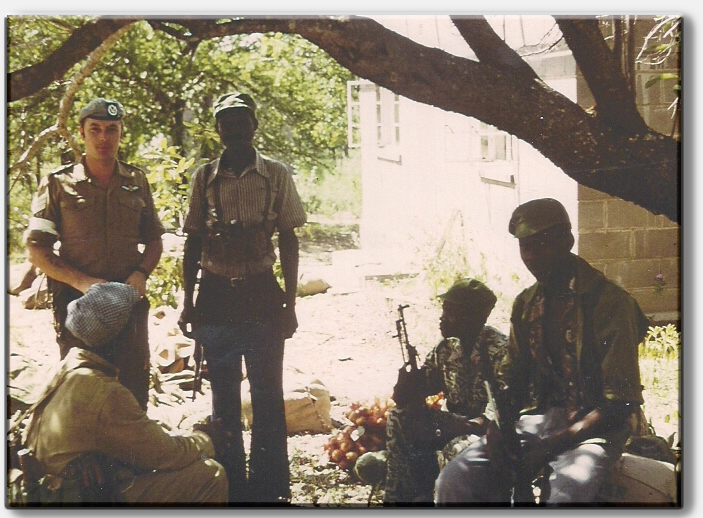

Sgt CK waiting to pickup a casivac NE of Bulawayo

Conduct of Operations

The CMG’s role was to monitor the activities of the PF and the RSF and report any violations of the ceasefire – it had no powers to intervene in the event of a recurrence of hostilities, nor indeed was it equipped to do so.

During the first month of the deployment, the Squadron’s twelve aircraft flew 1000 hours in the hot and high local conditions which varied from 1500 to 8000 feet above mean sea level – REME, as ever, worked wonders and ten helicopters were always available for duty. The chief problem areas for the Squadron as a whole concerned the availability of adequate refuelling facilities and of suitable accommodation, the need for better radio sets and of extra means of land transport. It was noticed that the pilots’ navigational and map-reading skills improved,

T/O after Re-supply mission to an AP somewhere.

‘Some of our better routes were over 100 nm of absolutely flat bush with no navigational features at all. You just had to rely on the compass and the clock and then amaze yourself when, at the given time, your destination suddenly appeared.’

Although, by African standards, Rhodesia had a well-developed network of road and rail links, in reality there were thousands of square miles of featureless flat bush to traverse. Off the main tarmac roads transport was restricted to bush tracks which, at the time of the deployment, were considered as a potential landmine hazard. Air support was therefore absolutely crucial to the CMG’s mission. The guerrillas were well-armed and before deployment the potential threat had been assessed as quite considerable.

There was only one confirmed case of a helicopter being fired at from the ground, this was on 25 February and no damage was sustained. The daily flying task included the movement of men and stores, liaison sorties, casevac, delivery of mail, newspapers and medical supplies, a flying doctor service and the pay office run. A ‘milkrun’ service was instituted serving each location across the country, which guaranteed (weather permitting) a visit by a Scout or Gazelle every forty-eight hours. The Scout was by this time a well-loved and proven workhorse; however, the Squadron noted with considerable satisfaction that the Gazelle was really good too.

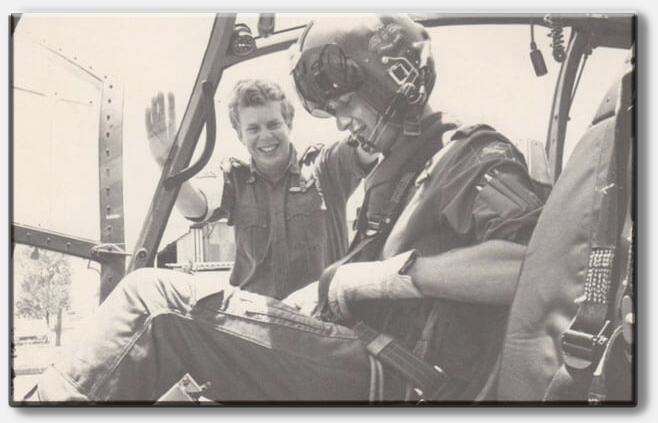

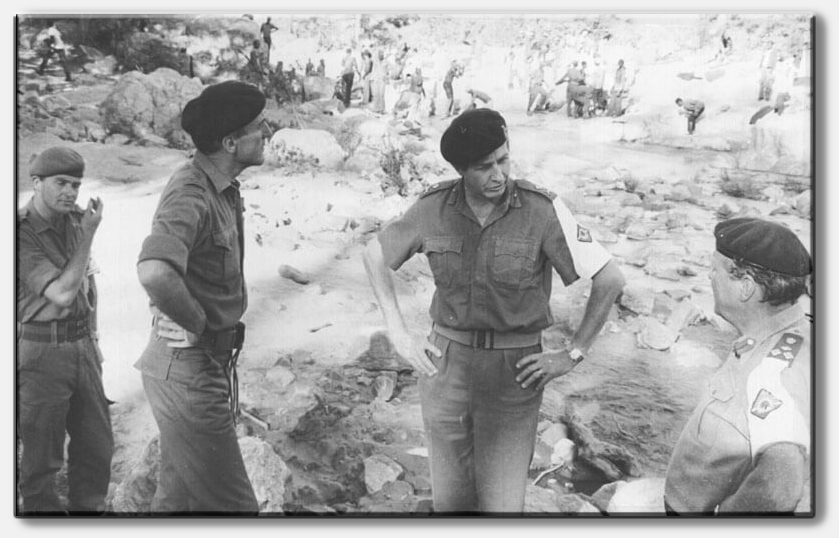

Both Flight Commanders in a rare photo together

Summary of Achievements

During its time in the country the Squadron flew 1,000 sorties in 2,200 flying hours, carried 2,000 passengers and 100,000lbs of freight (incidentally finding out that a Gazelle could carry a load of twenty-five empty jerry cans) and covering 250,000 miles (the RAF’s Hercules delivered no less than 1,000,000lbs of stores during the first thirty days – the biggest such operation since the Berlin Airlift).

The Squadron was also tasked to fly to Mozambique and Zambia and ‘bent a Gazelle doing engine-off landings.’ Towards the middle of February tension increased once more and many sorties were flown to the APs to enhance the stocks of arms and ammunition stored in the armouries – just in case the situation turned nasty and CMG troops had to fight their way out. No doubt it felt a little similar to Rourke’s Drift. Thankfully the worst case scenario did not happen and in the last week of the month the Squadron flew members of the Ceasefire Commission, which included Major General Sir John Acland, the CMG Commander, as well as senior officers of both the PF and the RSF, around all the APs.

ZIPRA Commissar awaiting his ride to his AP

Within a week a training camp had been set up for ZIPRA forces, where British officers and SNCOs began to work with them. A similar camp was planned for ZANLA, while Rhodesia police and soldiers began to take over the administration of the APs. It seemed to a relieved Major Nathan like a minor miracle and just in time in the light of the election results which would, ‘shake the whole establishment to its foundations.’ The election results were announced on 04 March. ZANU (PF) led by Robert Mugabe won this election, some alleged, by terrorizing those who opposed ZANU, including supporters of ZAPU. The observers and Lord Soames were accused of looking the other way, and Mugabe’s victory was certified. Nevertheless, few could doubt that Mugabe’s support within his majority Shona tribal group was extremely strong.

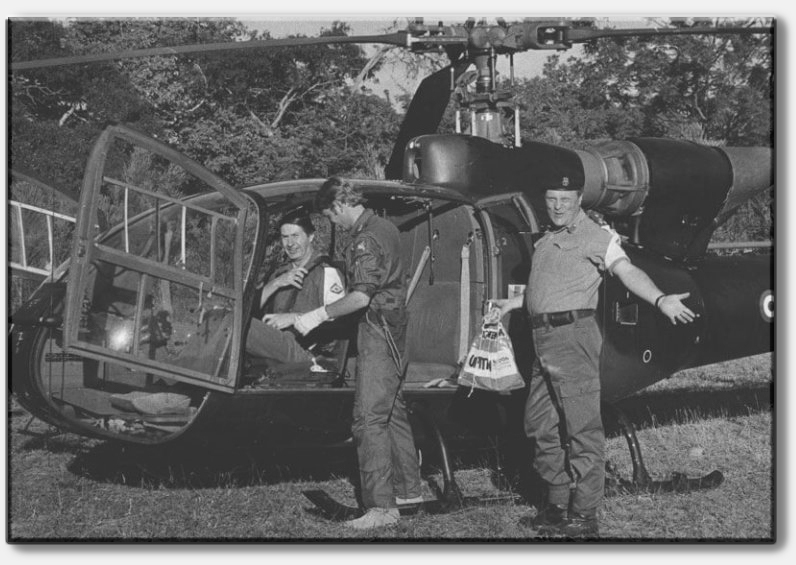

Maj Stephen Nathan and Brig John Learmont with a 656 Squadron Gazelle in Rhodesia

It is believed that elements in the Rhodesian armed forces toyed with the idea of mounting a coup against a perceived stolen election to prevent ZANU taking over the government but this was never realized. On 18 April 1980, the country gained independence as the Republic of Zimbabwe, the Union Flag was lowered for the last time from Government House and the capital, Salisbury, was renamed Harare two years later.

Almost as soon as the Monitoring Force had departed Mugabe began to settle old scores, firstly against supporters of Joshua Nkomo in Matabeleland and then eventually against the white farmers, with the unhappy results stretching into the twenty-first century. However, for the Squadron, its involvement had come to an end on 10 March, when the first return flights commenced, with everyone being back in the UK by 19 March. Brigadier Learmont wrote a letter of appreciation to the OC,

‘In the early days you and your pilots were literally the lifeline for the soldiers at the RV points … it was a magnificent performance and will never be forgotten by those whom you supported … As one of your more regular passengers, I would like to record that it is a privilege to have been flown by 656 Squadron.’