The Early Days (India and Burma)

India, First ImpressionsCampaign HistoryMove into BurmaFirst CasualtyBattle of the Admin BoxSquadron NewsletterDeolali RefresherReturn to OpsEnd of Ops in SightThrust to MeiktelaVE DayOC's SummaryDeparture for India

The Squadron main party departed from Theydon Bois Railway Station at a quarter past midnight on 12 August 1943 for an unknown destination and after a cold but comfortable journey were surprised at dawn to find themselves de-training in Liverpool and then proceeding by tram for the journey to the docks. At the quayside they encountered their first clash with authority because the RAF embarkation staff, seeing the mixture of uniforms, tried to separate the soldiers and airmen. Major Coyle thought otherwise and insisted that the Squadron should fall in by flights.

However, the movement staff finally won because, when they boarded the 24,000 ton SS Monarch of Bermuda, a former luxury liner, they were split up into penny packets in three separate parts of what was also discovered to be a ‘dry’ ship.

After twenty-fours hours hours in the mouth of the Mersey, during which time, ‘the men experienced their first problems with climbing into hammocks amid great amusement’, they sailed for theClyde, where a convoy was assembling, and eventually proceeded to sea.

The voyage is very well described in the Squadron diary:

‘16 August: The ship set sail again at about 1800 hours, passing the Isle of Man and Ireland into the open sea. The convoy was large, about twenty ships (apparently all troopships) and including an escort of HMS Shropshire, one aircraft carrier and at least six destroyers.

18 August: The convoy passed well into the Atlantic (presumably to avoid U-boats).

19 August: The first depth charges were dropped by a destroyer in the escort. Some Squadron officers attended the first Hindustani lesson by Pilot Officer Singh. The course lasted the whole voyage, but Squadron officers soon gave it up in despair.

22 August: More depth charges were dropped by an escorting destroyer. HMS Shropshire came in close in a farewell salute, as she was going on via the Cape to Australia. Tropical kit was worn for the first time.

23 August: The convoy passed through the Straits of Gibraltar at dawn. Gunfire from all ships was directed at an enemy

aircraft at 1000 hours. In the afternoon we passed a large convoy of seventy ships.

26 August: Just glimpsed Malta on port side in the morning, temperature beginning to warm up. The men were informed that this was the first convoy through the Mediterranean since Italy joined in the war and the Germans blocked the Suez Canal. [Axis forces in North Africa had surrendered on 13 May].

27 August: Approximately twelve depth charges were dropped very close to the ship at 0435 hours. Sighted a large convoy on its way to invade Italy.

30 August: The convoy reached Suez at 10.00 hours, where passengers for the Middle East disembarked. The Squadron baggage party, under Captains Jones, Moffat and Maslen-Jones, were working hard all day. They took all Squadron hold baggage ashore in lighters and spent the night with the baggage at Port Tewfik.

31 August: Squadron personnel were transhipped from the Monarch of Bermuda to HMT Ascania 11,000 tons, a converted merchant cruiser and former Cunard liner, a dry and incidentally, very dirty ship, sailing without escort. The move went off very smoothly.’

Bombardier Ernest Smith also had very fond memories of the voyage,

‘The ship’s kitchens were geared to catering for passengers who had paid a lot for their journey and the grub was wonderful – they baked beautiful bread daily, we had real butter (strict rationing in Blighty, remember) and eggs for breakfast every day.

The sea was quiet, dolphins and flying fish intrigued us and the men of the South Wales Borderers sang to us beautifully on the main deck in the evenings.’

At this time Major Coyle made firm representations to OC Troops that the Squadron should be treated as a single unit, with the result that all personnel were accommodated on the one mess deck. On arrival they did not know what to make of such a peculiar RAF unit with mixed personnel and asked whether they would like to lodge in an Army or RAF transit camp. Enquiries elicited that the RAF camp at Worli was more comfortable and so this was the one that was chosen and it was certainly more suitable because it had a ‘very nice little’ airfield at Juhu, ‘on the sea, lovely beach, bathing and palm trees.’

India

First impressions of India were mixed,

‘a hair-raising ride in lorries driven by Indians to Worli. Everybody eating lots of fruit – issued with mosquito nets.’

Gradually, the manifold problems were overcome by dint of, ‘improvising, legitimate borrowing, scrounging and diplomacy.’ One of the major difficulties was, of course, the complete lack of aeroplanes, which they were advised had only left England on 12 September. The OC decided that he needed to visit the MGRA in Delhi and flew there by RAF Lockheed Hudson on 22 September. He came back with the news that the Squadron would move to the School of Artillery and airfield of Deolali and had been ordered to be ready for jungle warfare by 31 December. As Denis Coyle well knew, the Squadron was to move as swiftly as possible to India to join 14th Army and help push the Japanese out of Burma.

As a consequence, the Squadron made preparations to move to Deolali, by rail. SS Delius had been located in Bombay harbour and arrangements were set in hand to unload the many crates of carefully packed Squadron stores and transport them to Juhu. A visit of inspection was made to Deolali by the OC, four officers and two ORs. The C Flight diary for 01 October recorded,

‘The main body of the Squadron moved to Deolali; entrained at 1200 hours with officers travelling Second Class and ORs Third. Tiresome journey – train seemed to stop for hours at every station. Arrived at 1830 hours and transported by truck to camp. ORs in huts and officers in tents.’

Training recommenced almost at once, covering such topics as small arms drill, toolkit maintenance, map-reading, radio operation, first aid and field engineering, as well as lectures on ‘Hygiene in the Jungle’ and ‘The Japanese Characteristics.’ Time was also set aside for swimming, football and cricket.

On 28 October news of a considerable setback was received from Juhu. A disastrous fire had consumed much of the Squadron’s equipment stored there. However, there was also some good news, as with much effort Denis Coyle had managed to obtain four Tiger Moths on loan from two Indian Air Force Elementary Flying Training Schools. So early in November, the Squadron’s pilots could at last take to the air again for some much needed flying practice. The Tiger Moths were joined by the first Auster III on 21 November, four of which had arrived on board the SS Behar. Training continued with all personnel spending time attending the jungle school at Vada, ‘living rough, making a landing ground, jungle training, swimming etc. Conditions are very similar to the Arakan, Burma, and everyone loves it.’ Denis Coyle made the first landing on the new strip at Vada in an Auster III on 03 December.

Within a few weeks he was able to summarise the progress made as follows,

‘By the end of the year we had completed our “theatre conversion” including some very useful practice in observation of fire at the School of Artillery at Deolali. Our oldest pilot, Captain “Daddy” Cross, who had flown with Royal Naval Air Service in the First World War, ran a first class jungle camp which accustomed every one to the problems of living rough in their new environment.

Meanwhile there were signs that our Austers were about to arrive and we arranged for one flights worth to be offloaded at Bombay while the others were taken to Calcutta in order to save us having to fly them all right across the continent. Our work-up period had undoubtedly been a great success, with the exception of the fact that all the aircraft spares which we had so carefully accumulated before leaving UK, were destroyed by fire under rather mysterious circumstances.’

Frank McMath was engaged in experimental work fitting a long-range fuel tank to an Auster, which doubled its range from 150 to 300 miles. The OC retained the use of his Tiger Moth for the Burma campaign, preferring its superior performance to the Auster.

Campaign History

At this stage in the story it would be appropriate to pause and examine briefly the background to the campaign in India and Burma which the Squadron was on the point of joining. Following the attack on Pearl Harbour on 07 December 1941, the armed forces of the Japanese Empire launched a series of highly successful campaigns throughout South-East Asia and the Pacific. The invasion of Burma by the 33rd and 55th Divisions of Lieutenant General Shōjirō Iida’s 15th Army resulted in a fighting and painful retreat by the under-prepared and hastily assembled Anglo-Indian and Burmese forces. It must also be admitted that the ability of the Japanese forces had been underestimated by the British C-in-C, General Sir Archibald Wavell. By May 1942 and the onset of the annual monsoon rains, all of the country was under Japanese control, with the weary Allied troops back in India. An explanation of this devastating state of affairs was given by Manbahadur Rai, one of the Gurkha soldiers who fought in Burma,

‘The Japanese soldiers we encountered were well equipped and trained and had mastered the art of jungle warfare. They were disciplined with superhuman endurance and fought with ferocity and courage. They didn’t understand the meaning of the word surrender and would fight to the last man. They prided themselves on being the invincible warriors of the emperor. They had come – as they saw it – not as conquerors, but as liberators, with a divine mission to defeat the western colonial powers in Asia. The British defeat in Burma by the numerically inferior Japanese was the result of the Europeans’ tendency to fight from static positions. Their strategies were road bound and depended on surface lines of communication. The highly mobile Japanese troops, guided by native scouts along jungle trails, would infiltrate the British positions, forcing them to retreat. The British forces in South-East Asia at first were not prepared or equipped for such warfare.’

The next Japanese target would be India. There were two alternative invasion routes; via the western coastal strip – the Arakan or through the much more difficult hill country to the north. Following the costly and bloody failure of 14th Indian Division’s First Arakan Offensive in 1942 – 43, and during the rest of the year there was a fair degree of hard fighting and an expanding programme of ‘Tiger Patrols’ into Japanese held territory but no definite move by either side. The Allies were able to use this time to organize defences, digest the hard lessons learned, regroup, retrain, improve their battle techniques, further develop a jungle health and hygiene regime and experiment with innovative means of warfare – Brigadier Orde Wingate’s ‘Chindits’ operating behind enemy lines between February and April 1943 and the extensive use of air power – particularly transport aircraft.

Return to Top

The Move into Burma and the start of Operations

On New Year’s Day 1944, Lieutenant General Philip Christison’s 15 Corps of 14th Army (which itself had been formed in November under the command of Lieutenant General William Slim) began an offensive into the Arakan from the north. On 12 January 1944, the Squadron (less B Flight, which was left behind at Juhu to take part in a planned amphibious landing in South Arakan with 33 Corps, which was later cancelled) left Deolali for the Arakan front south of Chittagong, at Chota Maungnama. The road party, under the command of Captain Rex Boys, performed wonders in arriving on time to catch the SS Ethiopia at Calcutta on 23 January. Two of the vehicles were sent on, and covered 660 miles in 33 hours over the most appalling roads in order to deliver the wireless sets and cradles to Barrackpore to be installed in the Austers. Rex Boys later wrote about the journey,

‘As I was in the lead Dodge command car of a convoy of between twenty and thirty vehicles, others received the benefit of my dust. I had time to drink in the novelty of the sights and sounds of the Indian countryside. We passed through everything from semi-desert to near jungle, we saw hundreds of holy but hungry cows, hundreds of coolie women, with children at their breast, humping baskets of earth to make up the road; all the commonplace sights of India. We also saw some beautiful scenery and the occasional palace.’

Despite the novelty of the situation, it was deadly serious and Rex Boys was keenly aware of the trust which had been placed in him and the responsibility that rested on his shoulders. He recalled one particular moment when he walked back down the halted convoy, which was taking a rest in a coconut grove.

They disembarked at Chittagong on 26 January and drove a further 156 miles to their destination, which was only three miles from the Japanese front. It was not long before they had their first encounter with the enemy, again Ernest Smith recalled,

‘At Bawli Bazaar I seem to remember a bridge over a river and an open space in which a number of vehicles were drawn up. In front was a dirt road stretching ahead, blocked by stationary vehicles, some were on fire and one was an ambulance from which men were rescuing casualties. Suddenly, as we came to a halt, there appeared at the far end of the road a Japanese aircraft, seemingly at head level, flashes from its gun muzzles flickering along its wings. This was 656 Squadron’s baptism of fire and we did what seemed natural – out of the vehicles and down on the ground!’

The Squadron was placed under command of 15 Corps, with A Flight supporting the 5th Indian Division on the coastal plain and C Flight supporting 7th Indian Division, which was moving south down the Kalapanzin valley. Within twenty-four hours of the ground party joining up with the aircraft, a full-scale surprise Japanese attack by the 55th Division under Lieutenant General Hanaya Tadashi was launched, which cut off the two leading divisions and with them the Squadron. Its aim was to prevent any reinforcement of the Imphal front. The Squadron base was located at the very spot at which the Japanese had decided to cut the road to 5th Division, so everyone took the opportunity to dig in earnest and occupy a defensive position.

After a few days the road back to Corps HQ was cleared and they were ordered back to a safer position alongside the HQ, the move being accompanied by very intense Japanese air activity, mainly aimed at a very flimsy bridge which they luckily failed to hit. Meanwhile, C Flight was cut off for a further two weeks and spent an exciting and very frightening time guarding an ammunition dump which was frequently under shell fire, of which more below.

First Casualty

The Squadron suffered its first casualty on 04 February 1944, when Rex Boys was shot down and badly wounded whilst on a reconnaissance flight. He described his experience as follows,

‘I suppose what happened to me was part of the body of experience that led the Squadron to its subsequent successful operations throughout the campaign. It would certainly have been bad for our reputation and our morale to have turned away from danger. Anyway, I took off for the river, which was quite close, and flew up and down the banks seeing nothing. For the first time, I realized how little one could observe through dense forest, even at low altitude. The whole area could have been teeming with Japs for all I could tell.

Then I flew south to Taung Bazar. At once the Japs came swarming out of the village huts and began to shoot at me. I tried to count. Impossible. There were groups of men everywhere and flashes of small arms fire. Splendid targets, but I had no guns to call on. I saw no signs of vehicles or artillery. I was about to turn back when I realized I had lost control of my aircraft, which went crashing into the ground from about 500 feet. It happened very suddenly, no time to think.

I should have been dead, except that my guardian angel was watching over me and has continued to do so ever since. His main achievement was to put me down in a small clearing in the forest and prevent the aircraft from catching fire as it might well have done. I do not know how long I was unconscious, and the first thing I dimly realized was that I must get out quick. I opened the door and tumbled out bottom first, dragging my broken legs after me, and lay beneath the wing, losing consciousness again.’

His life was saved by the local Burmese who carried him through the Japanese lines to safety, but not before he had to suffer further, at one point being abandoned by his ambulance driver when they came under attack from Japanese aircraft.

The delays he endured before he reached medical treatment took their toll; gangrene had set in to his badly broken legs, and he was to spend the following ten months in hospital in India, Egypt and London.

Almost ten years later, the Spring 1953 edition of the ‘656/1587 (AIR O.P) Association Newsletter’ was happy to record

Splendid news is that Rex Boys is again in circulation. Rex will be remembercd as the C Flight Commander in the early Arakan days and our only wartime flying casualty. He has made a wonderful recovery from his very severe injuries and although still not fully mobile gets about remarkably well, and looks extremely fit.

Battle of the ‘Admin Box’

C Flight took part in the famous battle of the ‘Admin Box’ – an isolated, defended perimeter in which troops would dig in and force the enemy to take the initiative. They were part of a very mixed garrison of 8000, mostly rear area troops – including the staff of the Officers’ Clothing Shop.

Wisely and presciently, Slim had insisted that all soldiers, whether they were support staff or not, should be trained to fight. One of those surrounded by Japanese attackers was Gunner Reg Bailey, who would live for a fortnight on ‘two hard biscuits a day and a tablespoon of mushy bully beef,’ with a daily routine which included, ‘shelling, and strafing by aircraft in the daytime, and attacks by Japanese infantry at night.’ His location was Ammunition Hill,

‘It was perhaps 150 yards long, 30-40 foot high with steep sides and very narrow on the top, almost like a ridge. It was covered with trees and thick jungle. When we got to the top we found that slit trenches had already been dug right along the ridge by previous occupants, either Japanese or our own. For those of us on the top of the Hill it was rather like sitting on top of a fire on Guy Fawkes Night – flames everywhere and bursting shells and shrapnel screeching through the trees.

It was here that Sergeant R.A. Roe set a fine example and did what he could, probably more than anyone, to try and put out the fires, but was hit by a piece of flying shrapnel and injured in the throat. With great courage he dressed this serious wound himself and was later to receive a Mention in Dispatches.’

During the battle for the ‘Admin Box’ some of the Squadron’s technicians and drivers were cut off from their unit, and served as infantry. At one stage during a lull in the fighting they were bathing in a river when they were strafed and bombed by Japanese Zeroes. Fortunately there were no serious casualties. On 18 February, the OC, flying an Auster III, NK128, led ‘Coyle’s Circus’ (as he described it in his log book), a dozen US L-1 and L-5 light ambulance aircraft, into the 114 Brigade Box. Ted Maslen-Jones, who also flew casualty evacuation sorties with the Auster, comments,

‘Denis Coyle knew his way into this difficult LG and had also been made aware of the build-up of casualties in the ‘Admin Box’. He felt he was in a position to do something to relieve the situation. After this initial sortie the task of evacuating wounded from the forward areas was carried out by pilots of the US Army Air Force, flying Stinson L-5 Sentinels, an aircraft which was similar to the Auster, but more powerful, and adapted to carry up to three stretchers. These pilots were dedicated and fearless in their work. Theirs was truly a mission of mercy throughout the campaign.’

It reminded one of those on the ground who witnessed the event; of the arrival of Sir Alan Cobham’s ‘Flying Circus’ to his home town before the war. Denis Coyle later noted that this exploit had proved that any formation that could make a small landing strip would not be completely isolated and, as soon as the news spread around, every brigade produced a strip without being asked, which had the benefit of making the Squadron’s everyday job much easier. After this rather spectacular beginning, the Arakan battle settled down to a slogging match while the enemy were winkled out of their well-prepared and heavily defended positions and this period gave pilots a chance to settle down and learn the real art of observation. They were also able to fly at night, as although there were no navigational aids, one flank was on the sea, which provided an excellent natural substitute, while the beach provided extensive ALGs.

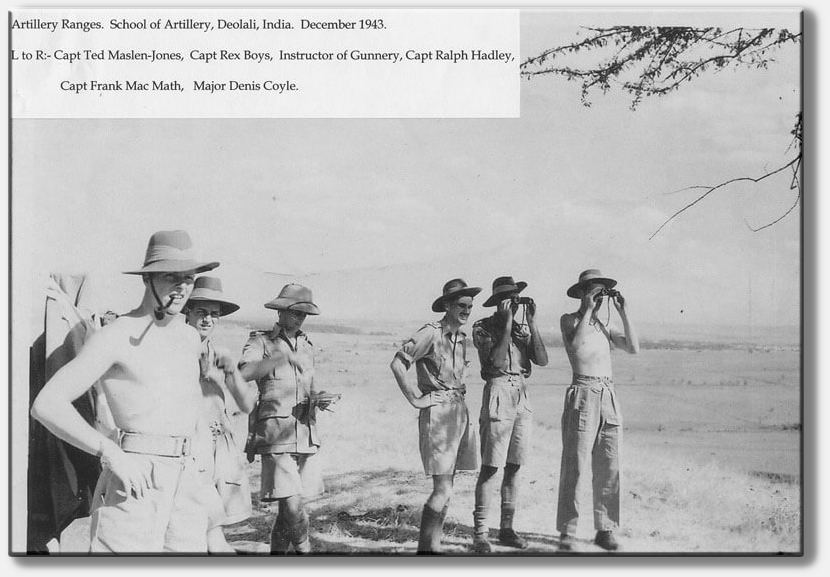

‘A’ Flight Captains Ted Maslen-Jones and Frank McMath in Burma

It was during this period that the Squadron’s pilots first realized that they were having an effect on Japanese artillery activity, the infantry were convinced that their presence in the air gave them peace to move around above the surface and Ted Maslen -Jones also noticed that the Japanese guns did not fire when his aircraft was facing towards them and that the best way of spotting their position was to turn away and look in the rear view mirror, which was actually provided to help spot any hostile aircraft sneaking up on one. As Ted Maslen-Jones explains,

‘The procedure was for our pilots to visit Divisional or Brigade HQ in order to establish codes and frequencies so that we could tune our wireless sets to individual units. We could, while in the air, change frequencies at will, so we were able to call on the most suitable guns depending upon the type of target. We also adapted the drill and techniques of OP work to the situation and type of country we were operating in.

One was not only above the target area and able to vary height at will, but ground positions could be viewed from different angles, even from behind, where camouflage perhaps had not been thought necessary. The height of the jungle canopy and the wind direction at the time were also important factors. Our eyes got used to the challenge of looking for Japs through the foliage, unusual tracks or signs of disturbance, discarded equipment and movement of any kind.’

A considerable quantity and variety of artillery was available for direction – Heavy Regiments with 7.2 inch howitzers, Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiments with 3.7 inch guns, Medium Regiments with 5.5 inch guns and Field Artillery Regiments with 25 pounders. The artillery certainly needed all the assistance it could get, as ground observers were greatly hampered by the poor visibility afforded by the thick jungle, making targets hard to identify, observing the fall of shot very difficult, and accurately adjusting the range and bearing a considerable challenge.

Squadron Newsletter

As a consequence of the hard fought lessons of the first three months in action the Squadron Newsletter dated 01 April, clearly highlighted the major lessons learnt, and the innovation and initiative shown,

‘We have learnt more in the last three months than in all previous training which, due to being a new type of unit, has been very theoretical. I wish we had more time to digest it. We have carried most things in our Austers from time to time, captured documents and equipment, money for local purchase, casualties, medical supplies and all the serviceable parts of Rex Boys’ aircraft. In general we need more time to decide exactly what our capabilities are out here. One thing that has most definitely been proved is that light aircraft for inter-communication are essential to this type of warfare.’

Aircraft.

Up to date we have been very lucky in that there have been no minor flying accidents so serviceability has been fair. Spares are, however, urgently needed. The Auster III is a most uneconomical aircraft for the type of work required of it in this country. Different aircraft have to be used for passenger carrying work, and work which requires wireless, because the removal and replacement of the wireless installation takes too long. The Auster IV will carry both and I think that a case could be made for this Front to have a priority for them. They should certainly be obtained for next season as they are the answer to the long-range problem as well.

[The radio in the Auster Mark III was installed to the right of the pilot, in place of a passenger seat.]

The Squadron suffered a serious setback shortly after arriving in India when all the stores of Squadron HQ, Maintenance Flight and Equipment Section were destroyed in a fire. On moving to the Arakan, a proportion of the deficiencies caused by the fire had been made up, but none of the aircraft spares which had been brought out from England with the Squadron were obtainable in India. One Maintenance Unit goes as far as to employ an NCO who specializes in the purchase of items in the black market.

The deficiency of aircraft spares has been made good by the cannibalization of aircraft and by the salvage of everything possible from crashes. [This was to remain a major problem throughout the campaign – when available, technical stores and spares had to be flown to the various flights by SHQ.]

Vehicles.

The new vehicles stood up to the cross-India journey very well considering the forced marches. There is no doubt that every Jeep must have a trailer, or else it is a most uneconomical vehicle. I do not consider that a motorcycle is of any use on this Front.

Layout.

One of the biggest problems seems to be to get the correct layout of the Air OP Squadron on the ground.

Conditions in the Arakan have not permitted us to keep Flights detached out to the Divisions, because landing grounds in Divisional areas are too vulnerable to keep aircraft on at night. The general principle therefore, has been to keep a Section manning landing grounds as required and to concentrate the bulk of the Squadron on a landing ground as near as possible to Corps HQ.

Landing Grounds.

Although there are no natural landing grounds except the beach in this part of the world, they take very little making. With the aid of a bulldozer and a grader, one can be made in four to six hours. This produces a very level strip, but it is liable to be soft and it shows up very easily from the air. A strip made by hand usually takes about two days, but as long as the paddy fields are the same level the results produced are better than the machine made one and as the lines where the bunds have been remain, it is very difficult to see from the air.

As yet we have had no experience of wet weather but we have two experiments in hand to deal with this. One is a bamboo matting surface which would be laid over a prepared strip. This I think will prove very slippery and we may have trouble with the tail skids catching in the bamboo. The other is a coconut matting strip on the same lines as those used in Italy.

Method of Operation.

The only difference in our method of operation from the standard one is in the heights at which we fly. The 600 feet rule does not appear to apply to this type of fighting. It is preferable to fly over doubtful country at 1000 feet rather than at treetop height: shoots can be done at 3000 feet sometimes flying directly above the target. It has been impossible to lay down any hard and fast rules about this, but every sortie has to be judged on its merits. The factors to be considered are, the position of the target, the position of the sun, and the resultant danger of being shot down by hostile aircraft, or ground fire from possible small pockets of enemy which may have infiltrated.

On the whole we have found that it is safer to fly high, but this is purely because up to now, enemy air activity has been negligible. We have tried to stick very rigidly to the rules of not being misused and this has been helped by the fact that we cannot carry both a passenger and a wireless set.

Communications.

The No 22 Wireless set has worked very well indeed both for ground-to-ground communications within the Squadron and air-to-ground for carrying out shoots. Even at night, with conditions at their worst, we have had twenty miles air-to-ground, the reception in the aircraft being the weaker of the two. Night flying has been carried out initially from a beach landing ground and later from a forward RAF strip. It has been found completely practicable and I hope that during the next period of moon we shall be able to take some shoots.’

Communication between SHQ and the other flights always presented a problem, simply due to the distances involved, as the nearest flight could be 100 miles away and the most distant up to 250 miles. The Squadron ‘wizard’ with the radio equipment was AC1 (later Corporal) ‘Nobby’ Clark who spread his knowledge and understanding of the No 22 set to all personnel, with the result that even when fully deployed the Squadron was comprehensively netted with HQ and all flights in contact with each other. This was a remarkable achievement when one considers that the No 22 set was designed to work over only a fraction of the distances achieved. He later designed a simple modification to the No 22 set, allowing it to be used as an intercom between pilots and observers in Mk IV and V Austers (who up until that point had to shout at each other).

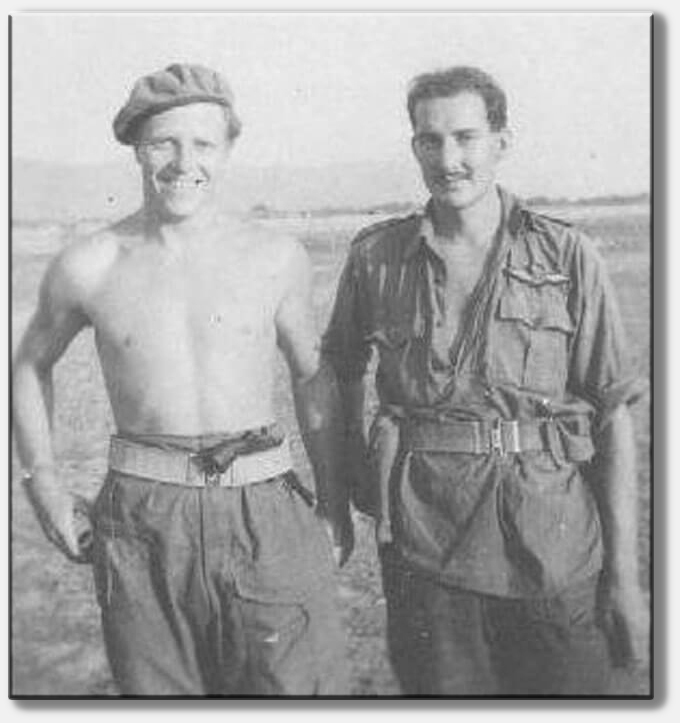

Radio wizard AC1 Nobby Clark in Burma, 1944

Arakan

A Flight would soon be on its own for several weeks in the Arakan at Bawli Bazar, as, in the middle of April, SHQ and C Flight were ordered to proceed the 900 miles to Dimapur to assist 33 Corps in the Battle for Kohima, in the princely state of Manipur, where B Flight had been working with 4 Corps at Imphal since the beginning of the month. A formidable Japanese offensive by its 15th, 31st and 33rd Divisions had been launched with the aim of:

(a) Crossing the frontier of India and seizing the main Allied advanced bases at Imphal and Dimapur, along with the immense stockpiles of stores and equipment held there.

(b) Cutting the Bengal to Assam railway, which was the lifeline for General Joseph Stilwell and his American and Chinese forces.

(c) Overrunning the Assam airfields from which the airbridge over the ‘Hump’ to China was mounted.

(d) Advancing as far as possible into India in the hope of fomenting a popular uprising against British rule.

General Slim, the GOC-in-C, decided to allow the enemy to cross the border and to fight it out on the high Imphal Plain, thereby lengthening the Japanese line of supply and shortening his own. The pleasant hill town of Kohima and the larger town of Imphal, key road junctions about 100 miles apart, were both surrounded and besieged and so began a fierce and desperate defence. In the meantime, A Flight Captains Deacon, Henshaw, Gregg, Maslen-Jones and McMath, carried on its valuable work until the onset of the monsoon at the end of May, the pilots averaging five sorties per day.

Pilots of C Flight, Arakan, Burma. Standing is Pat “Black Mac” McLinden. Sitting L-R are Jimmy Jarrett, John Day, Wally Boyd and Ralph Hadley.

On 27 April both Ted Maslen-Jones and Frank McMath flew as many as eight sorties on either side of the Mayu Range, with a combined total of some sixteen hours in the air. McMath had the east side and lived on a very unpleasant strip which had been built in the old ‘Admin Box’ and rejoiced in a furious crosswind during the hours of daylight. He flew continually in search of enemy guns and also undertook the Squadron’s first night shoot to cover the withdrawal of the 4th Indian Brigade. Maslen-Jones, on the coastal plain, carried out several deep reconnaissance missions and also gave close support to Royal Marines Commando operations behind enemy lines.

Through the mighty efforts of the defending forces, the Japanese invasion through the Arakan was utterly thwarted and ‘the triumphant 14th Army, having inflicted its first big defeat on the hitherto invincible Japanese stood poised and ready to reconquer the whole of the Arakan.’ During the first week of June, A Flight withdrew and made its way to Ranchi which was 250 miles north-west of Calcutta. Ted Maslen-Jones’ trip was given added interest when he landed at Dacca to wait for a storm to pass, where he was greeted by three jeeps, from which emerged a number of rather grim looking US Military Police. He was escorted to a dispersal bay, where he learned that the arrival of a bomb group of Boeing B-29 Superfortresses from one of the first raids mounted on Tokyo from India was expected imminently. As this involved a round trip of 6000 miles and several of the huge bombers were limping home, he could understand that he was low down the list of priorities.

B Flight had already moved to the Kohima – Imphal area after a marathon tactical deployment right across India, in which they covered 1,500 miles without seeing a recognized landing ground. The road party started out at 0900 each morning, followed two hours later by the Austers flying in pairs with a half hour interval between. The leading pair would overtake the convoy to look for the next landing site and it would then guide the next pair towards it. One of the four aircraft would then return to drop instructions to the lead driver below. From Calcutta to Imphal they travelled firstly by train, but completed the final 120 miles by road along hair-raising mountain paths with a sheer drop to one side.

They arrived in Imphal and settled in on the main airstrip just in time for the Japanese attack. The airfield was very crowded and the Flight was located amongst a number of dummy fighter aircraft which the camouflage officer had hoped would attract enemy attention and he was not to be disappointed in this wish as B Flight was greeted on its first morning by a couple of Mitsubishi Zeros carrying out low-level strafing. The Imphal siege, which lasted eighty days, was a period of intense activity for the Flight, who had an excellent concentration of guns and plentiful enemy targets to engage. Each section flew in support of one of 4 Corps’ brigades. There were four divisions in the valley, each with its own strip which was liable to be overrun at night, so the Flight remained based on the intensely busy main airfield which was operating up to 300 C-47 Dakotas, C-54 Skymasters and Vickers Wellingtons, as well as No 11 Squadron of Hawker Hurricane IIC fighters.

There was something of a dispute with the airfield control staff at first, who saw no need to make any allowances for the Austers’ limited fuel reserves while they waited for the green landing signal. Nor were they in any hurry to let them take off again, until it was pointed out to them that the artillery of an entire division – seventy-two guns – was awaiting the return of the Auster in order that they could get on with the war. Higher priority was allocated from that time onwards. In another incident on 21 March, Captain A.V. Cheshire crashed on coming in to land and in the words of Arthur Windscheffel, ‘the kite went completely for a Burton I’m pleased to record that Captain C came out alright and unhurt.’ A week later he reported, ‘Captain Cheshire missing, but found later that he had crashed again but was OK.’ Cheshire was rescued by another pilot and his Auster, MT369, was salvaged by an enterprising REME Lieutenant Colonel and a three-ton truck.

The lead elements of SHQ and C Flight having arrived at Dimapur, began operations on 17 April, then did their best to support 33 Corps in the Kohima Battle, in which it strived manfully to prevent the Japanese 31st Division from reaching the Assam Valley and also to keep open the road link with 4 Corps on the Imphal Plain. However, their activities were limited not only by the performance of the Auster III, which had an absolute ceiling of 7,000 feet, but also the need to operate from the nearest airfield, which was half an hour’s flying time away from the battle.

During this time Denis Coyle managed to pay one visit to B Flight at Imphal and to do this he had to use the Squadron’s one and only Tiger Moth, which was the only aircraft available with the range and ceiling to get through, but was, of course, entirely lacking in armour or armament. A description of a typical day’s activity is given by the C Flight diary for 07/08 April,

‘Captain John Day ‘pranged’ one mile from Bawli Bridge. After crossing the Goppe Pass he opened up the throttle with no effect, and successfully landed without undercarriage into a paddy field. Captain Day was OK but [Auster III] MK132 was u/s.

Captain Peter Kingston did a sortie over the battle area and did corrections for 30 Medium Regiment who were firing smoke just in front of our own troops. Tanks, dive-bomber Hurricane strikes were all very spectacular and successful. After the Fire Plan was finished, Captain Kingston had two Batteries of 30 Medium Regiment on tap for opportunity targets but nothing was seen.

Successful infantry attack for eighty-five dead Japs and two guns were found on the feature. Our own casualties were fifteen killed and about thirty wounded. Captain “Black Mac” McLinden carried out four Counter Battery sorties … but the Japs did not fire when we were up, which is most annoying (for us).’

Remarkably, even in the thick of battle, entertainment was provided by the redoubtable British stars who had bravely volunteered to travel to India, including, as the Squadron diary notes on 16 May.

Withdrawal for the Monsoon

By the end of May the monsoon had broken and there was very little more that could be done, so most of the Squadron emulated A Flight and withdrew to Ranchi for a refit and to change from the Auster III to the Auster IV. The return flight was not a complete success for all pilots, especially two of the trio who, after one and a half hours flying through cloud, emerged over the flood waters of the Brahmaputra River. When on the point of despair, they saw a little village at the edge of the water with a dry football pitch. The first pilot, Captain John Day, undershot, hit a bank, and finished in the villagers’ lotus pool. The second, Captain Ralph Hadley (who in civilian life had been a sports reporter for the News of the World), over shot and went straight into the floods, which taught the rest of the Squadron a useful lesson, because they thereby discovered that it was possible to get out of an Auster under water. The third pilot, Captain McLinden, came in downwind and landed safely.

Conditions at Imphal were dreadful, as Arthur Windscheffel’s diary records,

‘The beds are saturated and we are soaked to the skins – scarcely a chance to dry ourselves out in these downpours, let alone the beds. I wrung my trousers out before putting them on this morning. Heavy rain fell all day and everywhere a sea of mud, mostly knee-deep.’

There was some welcome relief for the hard-pressed fitters when, in the third week of July, Denis Coyle managed to organize three replacement machines to be sent up inside three C-47 transports. He wrote in the Squadron Newsletter,

‘I travelled to Imphal with one of the C-47s and spent four days with B Flight. Flying conditions within the Imphal Plain were surprisingly good and even the rain storms were insufficiently heavy to curtail flying. The cloud on the surrounding hills, however, cut down our possible use to a minimum and a waiting list of artillery registrations was mounting up. Only on the Tiddim road could we be used to full extent. By now the Jap will be beyond our reach.’

B Flight remained there until 06 September, when it too withdrew to Ranchi for a much needed rest and refit, arriving there on 22 September. By this time and having worked through the monsoon period, they had to abandon their aircraft as their fabric was rotted through. Denis Coyle estimated that in normal conditions fabric would last four months, despite the best efforts of the RAF to prolong its life by producing a more durable dope. The wooden propellers and the perspex cockpit canopies fared little better.

The CCRA of 33 Corps had a fearsome reputation and rejoiced in the name of Brigadier ‘Hair Trigger’ Steevens, who would arrive unannounced, ‘in his usual flurry of dust and screech of brakes.’ The Squadron and A Flight in particular, never had a moment’s trouble, finding him to be at all times supportive and indeed almost paternal in his attitude to them. Indeed, while at Ranchi the Squadron received the following letter, from Brigadier Steevens, which was one of several appreciative notes sent by CRAs or CCRAs,

From HQRA 33 IND CORPS 15 ABPO 11 June 44

656 Air O.P. Sqn R.A.F.

I should like to thank you for the excellent work you have put in for us up here. We have both, I think, learned a lot during the period you have been with us, and so should be ready to start again at high pressure as soon as the monsoon shows any sign of finishing. You have been most useful in carrying out accurate registration which we would not have been able to do without you. In addition to this your recce sorties have been of great value.

The fact that you have had no accidents, in spite of the very bad flying conditions here, shows that your maintenance must be of the highest order. I consider that your pilots have shown great skill and keenness in the number of flying hours they have managed to put in lately. I hope that we shall have C Flight again when we next co-operate together.

1587 (Refresher) Flight, Deolali

Ranchi was a pleasant and well-equipped garrison with hangerage for the aircraft and an artillery firing range on which to exercise with gunner regiments also on rest. Local flying included wireless practice and live shoots on the range. Off-duty hours could be filled with sport, visits to one of the three local cinemas and, for the more broad-minded, a fairly risqué stage show. Medical needs could also receive attention, even though the dentist was ‘pleasant but positively horrific.’

The taking of some well-earned leave was also a priority. Ted Maslen-Jones combined a visit to Calcutta with a chance encounter with Vera Lynn at the Calcutta Swimming Club and an impromptu ‘joy-ride’ over the ‘Hump’ to China in a USAAF C-47, flown by two pilots whom he had also met at the Club. The Squadron now received its only Indian pilot, Captain F.S.B. Mehta, who hailed from Bombay and on whom was accordingly bestowed the nickname ‘Duck’. He later went on to retire as a Brigadier in the Indian Army.

Other new pilots included Captains Pip Harrison and Ian Walton, recent arrivals from 1587 (Refresher) Flight in Deolali. The Flight had been set up by Denis Coyle on 16 October, 1944, and placed under the command of Captain R.T. Jones (who was succeeded by Captain Bob Henshaw in July 1945), with Captains Cross and A.W. Cheshire as the other instructors.

The Flight’s purpose was to provide in-theatre acclimatization for newly-qualified pilots sent out from the UK, specifically to give them experience flying over jungle, in hot weather, before they were sent out to 656 in Burma.

One of the trainee pilots, Captain Harry Groom, has fond memories of his period with the Flight,

‘Our posting was to Deolali where there was a Maidan (a municipal open area used for sports and parades) used solely by 1587 Flight as a base for flying training in tropical conditions. One of the instructors was Captain Cross RA whom we called “Daddy Cross”, he must have been at least forty five.

Without labouring the point, it is relevant to record that there were no navigational aids, no wireless contact, and no contact with control towers. Flying was ‘by the seat of the pants’ over the Western Ghats, (coastal mountain ranges) in local storms, over the jungle and in the foothills for low flying, but it was so absorbing. We were given practice in short landings and on the clear maidan into strong wind with full flap it was possible to put down in twenty yards.’

Aircraft operated included a Tiger Moth and five Auster Mk IIIs, which were replaced by three new Auster Mk Vs in September 1945. The Flight was disbanded on 31 December 1945, having trained a total of thirty-one pilots.

Return to Top

Return to Operations

With the ending of the monsoon in October 1944, SHQ and the individual flights could recommence operational flying. In the Imphal area, A and B Flights worked with 33 Corps and 4 Corps respectively and accompanied the troops as they advanced through Central Burma, while C Flight had already begun activity in the Arakan in September at Cox’s Bazar with a forward strip at Maung daw, supporting 25th Division.

The two areas were very different; the central front starting as dense jungle with few breaks in the canopy and the great teak trees rising to more than 100 feet, with high mountains on the right flank. Whereas the coast strip was a series of islands with a great deal of mangrove swamp and many beaches which could be used as ALGs.

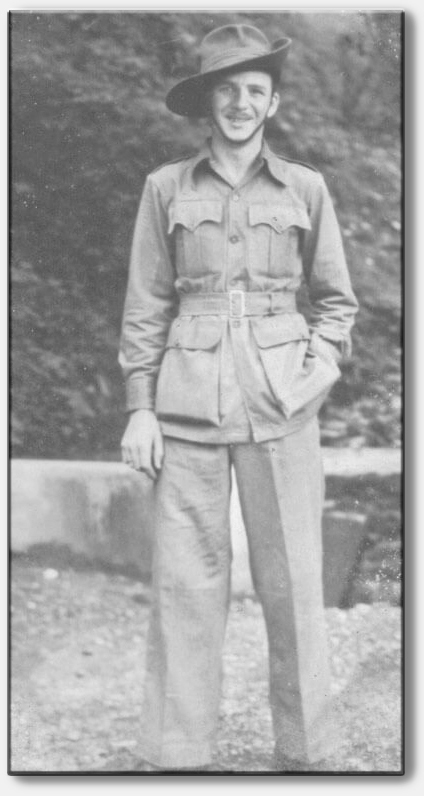

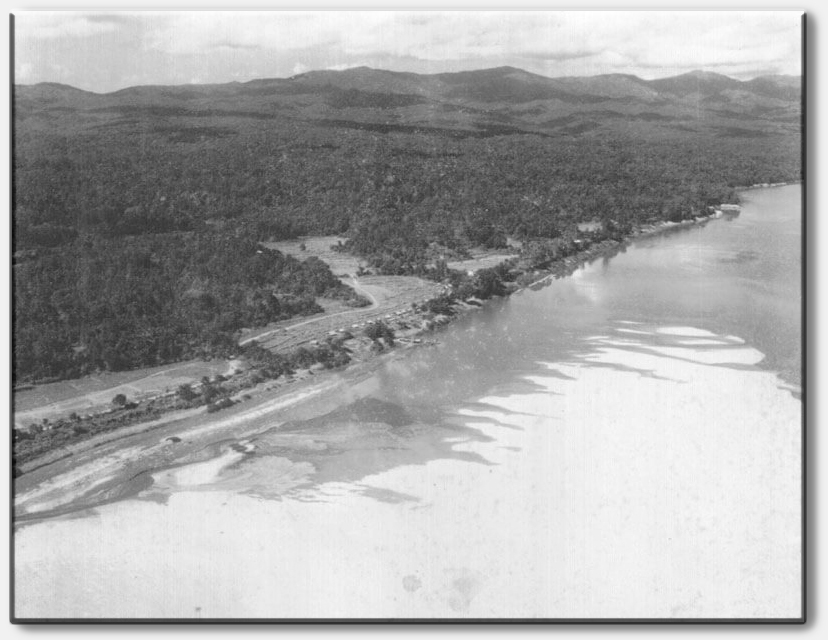

A photo taken by Denis Coyle, pasted into his log book – November 1944

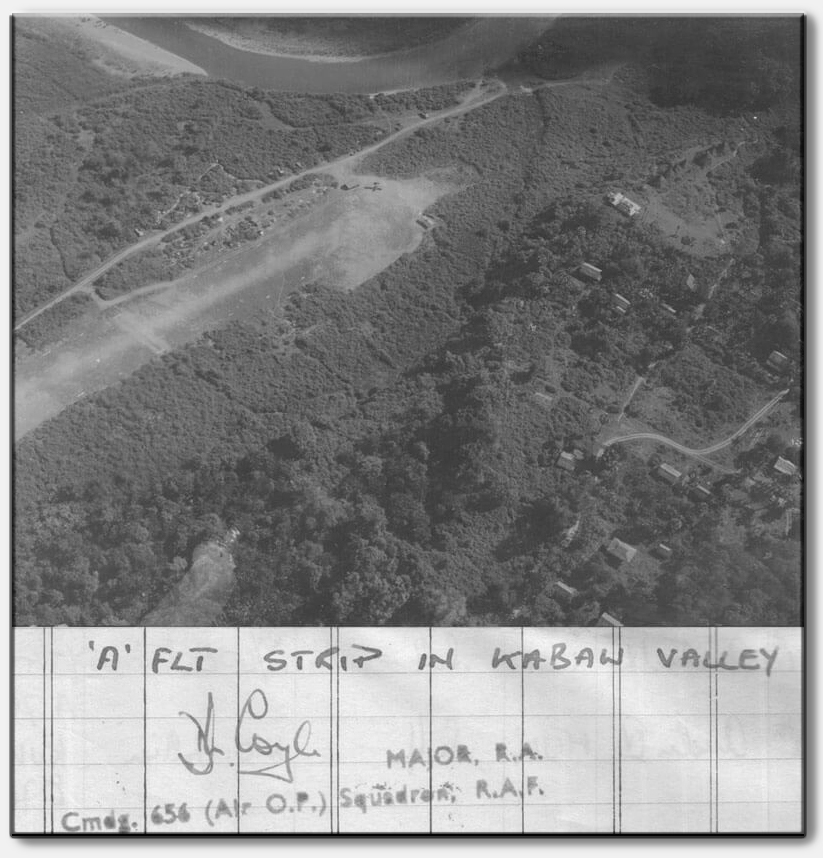

A Flight moved back into Burma on 05 November, working down the Kabaw Valley with the 11th East Africa Division as it advanced on Kelewa. This brought an unforeseen minor problem. As aircraft were operated a considerable distance from units being supported and radio sets were frequently in short supply on the ground, message dropping came into its own. Unfortunately, the Africans loved the highly coloured message bags and the only way of getting them back was to visit the units concerned and collect them from the entrances to the men’s tents and dugouts where they were hanging, presumably as a deterrent to evil spirits.

A Flight had moved from Palel (where SHQ would remain for several months) to Yazagyo, where they witnessed an appalling accident on their first night. A US Noorduyn C-64A Norseman carrying L-5 Sentinel reserve pilots, ran into a parked Tiger Moth after touch down, spun round and caught fire. Only one occupant managed to get out, but he died from his injuries, the other seven passengers perished in the flames.

A little later in the month supply problems led to a shortage of fuel for the aircraft at Honnaing. George Deacon sent a truck with his batman/driver, Gunner Embley and another soldier back to at Yazagyo to collect as much fuel as possible. Their epic overnight trip along unmarked tracks, through an area known to be used extensively at night by small parties of Japanese left behind in the retreat, who were bent on sabotage as they made their way back to their own lines, produced 200 gallons of petrol before first light in time for the dawn sorties.

By the end of November, the Flight had moved to the head of the Kabaw Valley, towards the western end of the Myittha Gorge. Frank McMath described the life of an Air OP flight in the jungle at Hpaungzeik,

‘We dug our holes and pitched our tents over them within thirty yards of the strip, but unfortunately this put us within ten yards of the road, and the road was the usual track covered in six inches of fine brown dust. The fog was sometimes appalling; aircraft running up their engines on the dusty strip and a convoy moving along the road would stir up so much choking dust that one could see barely five yards. Poor LAC Whitlock had his cookhouse almost in the thick of it and how he kept the food as clean as he did was a miracle.

But then he was always performing miracles. Sometimes, in the morning, we couldn’t see anything at all when this awful dust mingled with the early mists to create a real London pea-souper, which would show no sign of clearing whatever until the sun climbed quite high and got really hot. Then suddenly, the cold damp fog vanished and the full mid-day heat took its place with the temperature rising to as much as 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Between 10am and 4pm the air conditions were very turbulent, with constantly veering winds.

Although flying was restricted until about 8am by these fogs, we soon found that life at Hpaungzeik was going to be very hectic indeed as the leading East African Brigade forcing its way through the Myittha had been meeting stiff opposition.’

The Flight was used for two main tasks, firstly maintaining contact and communications with the gunner officer in the leading infantry company, searching for any sign of the enemy. In order to locate the foremost friendly troops, they habitually raised a great orange umbrella, which showed up perfectly amid the dense green foliage.

The second job kept a couple of pilots fully occupied from the time the mist cleared until dusk, ranging artillery on likely enemy observation posts, gun positions or bunkers. Ted Maslen-Jones had a very singular experience when he nearly succumbed to ‘friendly fire’ from a flight of Dakotas dropping supplies. He was crossing a supply dropping zone in a jeep driven by Gunner Vic Foster. Foster’s forage cap blew off so he stopped the jeep and reversed to go and pick it up. Just at that moment the Dakotas arrived and began unloading heavy bags of rice. Ted sprinted for safety and watched in horror as a falling bag took the front near side wing off the jeep. A nearby African collection party was highly amused and one was heard to shout, ‘Near miss, Sah!’

Frank McMath also had a brush with death when he borrowed Ted Maslen-Jones’ Auster for a shoot with one medium battery and two field regiments, giving him control of eight 5.5 inch howitzers, twenty-four 3.7 inch mountain guns and thirty-four 25 pounders. This was very successful, but involved so much flying that by the time he turned for home he was down to his last gallon of petrol. The engine stopped and he had no choice but to make a forced landing, fortunately into a patch of elephant grass which was 12 feet high and cushioned the impact.

In the meantime, his worried colleagues decided that Ted should take off on a search mission – despite the fact that the light was fading fast. He returned to make a difficult night landing with the aid of a flare path provided by the headlights of the Flight’s vehicles. Frank turned up unscathed an hour or so later. By good fortune he had landed close to the Medium Gun battery which he had been directing, who provided him with refreshment and a lift back to base. Kalewa fell in early December and by the middle of the month the advancing forces were across the Chindwin, which was bridged for the first time in its history by means of the longest Bailey bridge in the world, built by British and African engineers.

Christmas Day

On Christmas Day Auster IV, MT313, landed, and out climbed Denis Coyle and Mike Gregg from SHQ. They had come down to spend a few hours with A Flight and also to fly over the forward troops trailing behind them a home-made banner made from twenty feet of aircraft fabric, saying in huge letters ‘Merry Christmas’. The gesture was much appreciated by the soldiers crouching in their weapon-pits, as also were the packets of cigarettes and sweets which Mike hurled out of the side window. They then flew off to repeat the process with B Flight.

Higher command also approved, as a ‘nice’ signal was received from 14th Army in recognition of the sortie. A Flight also received a gift hamper dropped by a Dakota, containing cigars, cigarettes, sweets, biscuits and other assorted Christmas fare, which was accompanied by a card bearing the message

‘Happy Christmas to A Flight 656 Air OP Squadron from A Flight 62 Squadron RAF. Good luck.’

After spending a short period with the 5th Indian Division at Tiddim, B Flight was allocated to 4 Corps at the end of November and moved out with 19th Division at the start of its trek from the Chindwin to the Irrawaddy. They received the very sad news that Captain Cheshire had died at the age of twenty-four in hospital at Deolali on 29 November of polio which he had contracted while on leave, and also of the death of Gunner “Tubby” Cherrington of C Flight, who was only twenty-one, of burns received during a refuelling accident.

The landing strip on the Irrawaddy river, where ‘B’ Flight spent Christmas 1944.

On 09 December, Arthur Windscheffel and his section were the first RAF personnel to cross the Chindwin River and as he remarked with laconic humour, “Quite an honour in its way for the Section I suppose – though one I’d rather do without.” They reached Pinbon on 19 December, after which the Flight was ordered to rejoin HQ 4 Corps at Kalemyo. Christmas Day was spent at Tonhe without much enthusiasm from the men, ‘although there was Christmas cake and pudding and a beer issue,’ according to the Flight Diary.

By the end of the month it had covered some 700 miles by road in December alone and all personnel were relieved to be back in action rather than being engaged in ferrying aircraft and long-distance driving. C Flight had recommenced operations on 28 September, in the Arakan, where Captain McLinden carried out a reconnaissance and a battery shoot from Cox’s Bazaar. Soon, the entire Flight was working at full stretch from Maungdaw in support of 25th and 26th Indian Divisions, the Commando Brigade on the coast and 81st West African Division working down the Kaladan Valley.

Shoots were carried out with all units of the Divisional Artillery, many on supply dumps and buildings in the Buthidaung area. It also observed for warships; the Flight diary made mention of the first instance on 13 December, ‘Captain W Boyd did two shoots with an Australian destroyer – the first active “Combined Ops” by 656 Squadron – and was very successful.’ This was a fairly extensive operational portfolio and although additional pilots could be made available, the ground crew had simply to absorb the extra work required. There was no let up on Christmas Day as the Flight diary recorded,

‘Captain Jarrett took the CRA to Kwazan strip, flew a Yorks and Lancs casualty to ‘Bella’, took a crashed Hurricane pilot to ‘Julia’, went back to Kwazan to pick up the CRA, having to fly round for over thirty-five minutes while Dakotas persisted in dropping supplies all over it.

Later, with Captain Hadley he flew down to 74 Brigade and back. Lieutenant Hutt flew the Brigadier 51 Brigade on a contact sortie over Pt.1296. Captain Boyd did numerous contact sorties and shot a troop of 8 Medium Regiment on Pagoda Hill, Rathedaung.

Captain McLinden looked for three guns marked on captured Jap sketch, saw none, but he shot up trenches and did two registrations. Captain Day landed at Kwazan and flew on a search for a second Hurricane pilot.

Despite the activity, over seventeen hours flying time in twenty-one sorties, a good Christmas was had. Our scrounging and the rations, combined with the skills of LAC Scaife and Gunner Michael, producing prodigious platefuls of goose, duck, plum pudding etc. and the Flight lay about in bloated heaps all afternoon.’

Third and Last Offensive in the Arakan

The third and last offensive in the Arakan had begun in earnest on 14 December. The coastal strip was narrow and the guns kept to the shoreline. The beach was wide and firm and stretched the whole length of the coast from Cox’s Bazar to Foul Point at the tip of the Mayu Peninsula, making perfect ALGs above the high-water mark for the Auster IIIs which C Flight preferred.

The job of the ground crew was not made any easier by the sand, which got in to the petrol systems and the wheel bearings. Despite their best efforts, on 28 December, Captain Boyd suffered engine failure when flying NJ777 on an artillery shoot against an enemy line of supply and had to make a forced-landing five miles inside supposed hostile territory. When he made his way to a settlement, he was greatly relieved to find out from the villagers that the Japanese had departed. They escorted him to the coast where he was met by an Air-Sea Rescue Hurricane, which directed a patrol to pick him up in a Bren Gun carrier.

He returned to the Flight none the worse, but rather tired after a lot of walking. When the Flight Commander, Captain Jimmy Jarrett, set out with a repair and salvage party a few days later, he found that most of the fabric had been stripped off and recycled as clothing by the very satisfied and cheerful Burmese.

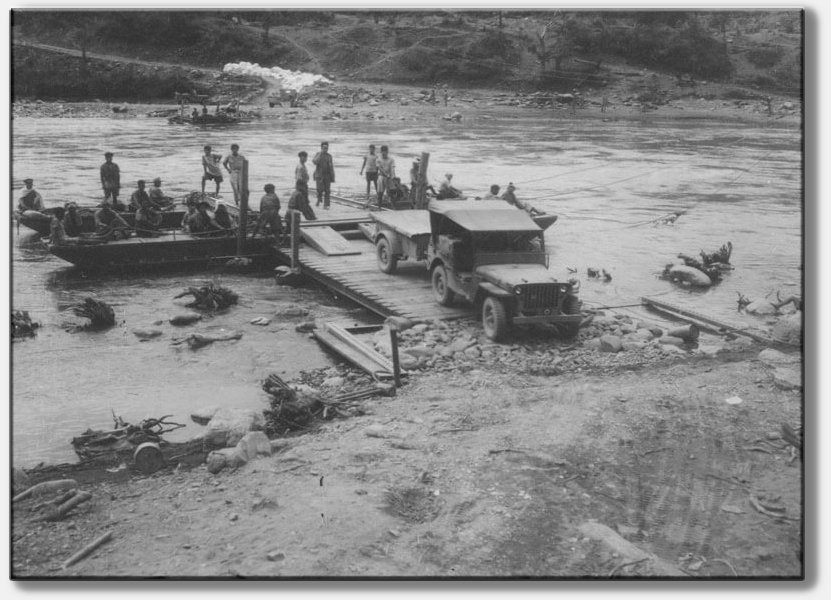

Another photo from Denis Coyle’s log book – a typical river crossing in Burma, this one is on the Tiddim road

At the end of December 1944, with SHQ at Palel, the three flights were spread over a front of 320 miles; from B Flight in the northern area of the Chindwin with 4 Corps, to A Flight which was 150 miles to the south at Kalewa with 33 Corps (both with Auster IVs) and C Flight (still operating Auster IIIs) in the Arakan alongside 15 Corps. The activities of SHQ included cable-laying, photography and a certain amount of transporting senior officers, but its main purpose was to supply the outlying flights with all they needed in terms of support for men and machines.

The installation of long-range tanks, when required, made visiting C Flight a much more feasible proposition. A story is told of a SHQ aircraft, commuting between flights about 100 miles across jungle and mountains, which landed on an abandoned strip in the jungle to liaise with an independent unit. At that time, Auster IVs were continuing to have over heating trouble, which made re-starting a hot engine a chancy business. Returning to his machine after a long walk along a deserted track, the pilot saw a sinister-looking African nearby, equipped with rifle and machete. The pilot swung his propeller for a very long time without success. At last the silence was broken by the African who uttered the terse but telling comment, ‘Bad maintenance, sah.’

However, SHQ was not the sole repository of technical expertise, as noted by McMath again,

‘Another problem was our MT, which had begun to show unmistakable signs of disliking the Burmese road surfaces, but which we knew well, would have to be coaxed through several thousand more miles before the grave. We were lucky here in having a couple excellent fitters, Lance Bombardiers Tom Topliss and J.G. Wiggins, who individually had their faults, but together produced a mixture of caution and daring, of technical skill and enthusiasm which overcame all mechanical troubles and very soon had the Section vehicles ready for anything.’

End of Operations in Sight

The campaign moved on to a much more free flowing stage before this successful experiment could be exploited operationally. Aerial photography was shown to be a useful adjunct and SHQ was authorized to indent for K.20 cameras and film.

They tried to keep passenger flying to a minimum, or it would have become a full-time job. One such mission was, however, accepted with some alacrity in November, as it involved taking a party of nursing sisters from Imphal to Tiddim, to join 5th Indian Division which had been smitten by scrub typhus.

The flight took an hour over some of the most inhospitable country in the world, but the girls, who were novices in the air, did not even turn a hair when they saw where they had to land. The Tiddim strip was at about 6000 feet and consisted of 300 yards bulldozed off the top of a mountain spur, with a nearly sheer drop of about 3000 feet at each end.

The take-off in particular was very spectacular as the aircraft would sink out of sight after leaving the ground and take at least a minute of hard climbing to regain the level of the strip.

The much desired and appreciated mail from home was delivered weekly by an Auster ‘milk run’ and once a fortnight the Adjutant, Flight Lieutenant Arthur Eaton, made his rounds with the pay. SHQ also noted in the OR Book that Flight ALGs had been visited in January by Lieutenant General Sir Oliver Leese, C-in-C ALFSEA and also by the newly-knighted Lieutenant General Sir William Slim.

General Leese remarked

‘I want to congratulate you on the magnificent work you fellows are doing on all fronts. Everywhere I go I hear praise from everyone on the work Air OP is putting in. Please pass on my thanks and those of Lieutenant General Slim to all ranks.’

It was well-merited praise, in December alone the Squadron’s ten Auster IVs and eight Auster IIIs had flown 898 operational sorties and had accumulated 722 flying hours. There would be no slackening of pace, as this would increase by 25 per cent in the following month.

1945 A Flight was now in open country and learned from Brigadier Steevens when he paid a visit on New Year’s Day, that its workload was to increase and as was recorded in the Flight diary,

‘As well as the British 2nd Division, we were now to support the 19th Indian Division, which after a prodigious march across North Burma had now turned south and was about to take up position on the left of the 33 Corps advance.

On the right, between 2nd Division and the Chindwin, the 20th Indian Division was moving into place and had already contacted the enemy.

So, instead of supporting one Division along one axis of advance (which was the correct function of an Air OP Flight), we were henceforth to observe for three Divisions, covering a battlefront of a hundred miles in length.’

On the same day back at SHQ, as the OR Book reported,

‘Today the OC inaugurated the Squadron “Hump run” by flying from Gangaw across the Chin Hills to Chittagong flying MV352 in five hours with one stop. Pilots who have done the same trip since quote variously from 6800 to 10200 feet as minimum height to clear the hills and/or clouds. A well-loaded Auster IV usually makes very heavy weather of any height above 7000 feet.’

The Woman’s Auxiliary Service (Burma), which had been established in 1942 and was known colloquially as the ‘Wasbies’, consisted of intrepid and dedicated ladies who saw it as their duty to press as far forward as possible in their self-propelled mobile canteens to bring a degree of home comfort to the men. They also ran dances and other entertainments and also operated static canteens, such as the Elephant Arms at Imphal. As its official history stated, ‘They took with them wherever they went an atmosphere of home and a concern for welfare of men that only women can give.’

In contrast, C Flight began 1945 with a really noteworthy exploit; the capture of Akyab Island, which had been heavily defended by the Japanese and which it was planned to recapture by a major combined operation including bombardment by a considerable force of land based artillery; one 15-inch gun battleship (HMS Queen Elizabeth), three 6-inch gun cruisers (HMS Newcastle, HMS Nigeria and HMS Phoebe), six destroyers, forty-eight B-25 Mitchell bombers, seventy-two P-47 Thunderbolts, thirty-six Hawker Hurricane IV “Hurri bombers”, forty-eight Bristol Beaufighters, twelve P-38 Lightnings, twelve B-24 Liberators, and two dozen Supermarine Spitfires.

Forty-eight hours before the assault was due it was discovered from observation by Captain ‘Black Mac’ McLinden that the enemy had left and the local inhabitants were waving white flags and had cleared an area to land on the main airstrip.

Captain Jimmy Jarrett was ordered to go and see if any of the local inhabitants, who were known to be pro-British, were in the target area. On landing, he found them busy making haystacks and in a very cheerful state of mind because they said the Japanese had finally gone. Having reported to Corps HQ he was somewhat bewildered by the statement that the assault must take place as planned and, because he had some suspicion that his evidence was doubted, he returned to Akyab to collect the Headman and took his batman, Gunner Carter, with him to help control the crowd.

On landing, after being wished a happy New Year and given three cheers, along with similar salutations for the British Empire, King George VI, and Winston Churchill, he called for the Headman and about ten rushed forward and tried to get into the Auster at once.

The landing went smoothly and the movie cameraman, who was being flown overhead by Captain John Day, had a field day taking impressive shots of Commandos storming up the beach. When everyone was firmly established Lieutenant General Sir Philip Christison, GOC 15 Corps, landed in an L-5 and took over the Military Governorship from Gunner Carter, who meanwhile had been royally treated by the village elders and plied with coffee and fried chicken.

This was the start of a period of intense activity for the Flight, flying no less than 145 sorties in seven days. The next target for the advancing troops on A and B Flights’ fronts was the Irrawaddy River – the greatest river barrier faced by any Allied army in the entire war. In a move of brilliant daring 4 Corps had marched in total secrecy 100 miles around the rear of 33 Corps with the aim of crossing the Irrawaddy further south and seeking a decisive encounter with the enemy at Meiktela – the main enemy administrative and supply centre, while 33 Corps pressed on to the city of Mandalay.

One of the Squadron’s regular tasks was to search for concealed Japanese gun positions, some of which may be seen here.

The two flights supported 33 Corps and 4 Corps in their crossings of the Irrawaddy. Numerous airstrips were used and the flights changed locations nearly every day. Once out of the jungle and on to the central plain around Mandalay the battle moved much more quickly and the Japanese presented many more worthwhile targets for the pilots to engage. Ted Maslen-Jones remarked to his CRA that a blackboard would be useful in explaining the state of play around Monywa. On returning from a sortie, he was somewhat astonished to find that not only a board but also coloured chalks had been provided and that his Divisional Commander, Major General Douglas Gracey, his CRA, and the Brigade Commander were waiting, sitting on the ground for Ted to begin his exposition. He thought of asking for an easel but decided not to push his luck.

The level of appreciation of the work of the Air OP pilots may be deduced from, the then, Captain ‘Wally’ Hammond, who was Gun Position Officer of 34 Battery, 16 Field Regiment RA,

‘On the ground in Burma we eagerly looked forward to the two to three sorties per day and the cheerful “no nonsense” voice of Pip [Captain S.N. Harrison] as he joined the net and made his report; maps were updated, information noted and any fire orders answered with alacrity. He was a first class shot.

The Air OP/Artillery co-operation by this time was near perfect: gun response was quick, communications excellent and misunderstandings very few and far between. There is no doubt that 656 was a great help to us on the ground during the advance. A good, regular flow of excellent, up-to-date info – not otherwise available – allowed us to follow progress on our immediate front.

Early target registration anticipated possible problem areas. Pip was a much-respected addition to the Regimental family and I am sure he was equally appreciated by the other two Regiments (10th and 99th). I recall that, on occasion, he would be registering guns from three or four units at the same time, ordering corrections for one gun, while the shell from another was on its way.’

Thrust for Meiktela

In March, supporting 17 Division, B Flight took part in a combined armoured and airborne thrust for Meiktela, thus cutting off the remaining Japanese forces defending Mandalay. This caused a vigorous Japanese reaction and the largest concentration of Japanese artillery which the Squadron was to encounter. The battle for Meiktela was one of the most fiercely contested of the entire campaign.

B Flight set themselves up initially on a strip on the edge of the town which came under observed artillery fire and they were forced to withdraw into a very congested area on the edge of the lake. They were at full stretch supporting two Divisions without the benefit of reserve pilots.

Denis Coyle flew in to visit them and was rather horrified to find that their new strip was marked by a fuel dump on the water’s edge and a line of tanks being maintained on the other side of the strip. There was just sufficient width for an Auster, as long as the tanks were kept in line, but the tank crews did not seem to understand that it really was not ideal for an aircraft landing or taking off to be suddenly faced with a tank in its path.

It is noteworthy that A and B Flights took part in every important battle of 14th Army’s victorious campaign, from Palel to Rangoon, as the Japanese put up a grim and ruthless resistance to the now irresistible Allied progress. By the third week of March, the Japanese defensive positions had been broken and a speedy Allied advance began, with the result that the need for Air OP temporarily lessened. This was fortunate, in that the hard-used Austers had begun to develop engine trouble. However, such was the rapidity of progress, that on several occasions A Flight pilots flew sorties simply to establish the forward position of the advancing troops and the pace of activity picked up once more.

Denis Coyle was recalled to the UK at the end of March for a series of conferences and discussions on the proposed Air OP Wing. Captain Shield assumed command until his return a few weeks later. The weather was becoming an ever more important factor for both A and B Flights. Captain Pip Harrison of A Flight flew straight into one such storm and found that his Auster could make no progress, so he had to turn and flee downwind to an old landing ground, where he hurriedly landed and tied the aircraft down until it had passed.

C Flight had a particularly busy time in the first quarter of 1945 as Allied troops island-hopped along the west coast, landing on the Myebon Peninsula on 12 January and on Ramree Island ten days later.

The only fatalities directly due to enemy action suffered by the Squadron occurred on 25 January, when the vehicle carrying Lance Bombardier Dougie Gibbons, AC2 H.E. ‘Taffy’ John and AC2 R.J. ‘Mac’ McCauley struck a landmine, killing all three. They were twenty-one, twenty-three and twenty-four years old respectively. C Flight’s diary described 12 Section’s heavy loss in Captain Bob Henshaw’s own words,

‘We were driving down the alleged de-mined road and came to a flimsy wooden bridge over a dried up river bed. As we seemed to be the first four-wheeled vehicle to cross the bridge I told the driver to wait whilst I checked the bridge supports and made sure the bridge itself was not mined. All appeared to be in order, although the bridge supports looked weak. I then walked across the bridge and told the driver of the Jeep to follow me, as I intended to get into the vehicle once we had crossed the river bed.

There was a tremendous explosion. They were all blown to pieces along with their Jeep and trailer. A crater about eight feet wide and six feet deep appeared. The explosion was so intense that there was virtually nothing left. I was walking about six feet in front of the Jeep, and although I was covered from head to foot in debris I escaped serious injury. I had a small cut on my hand, and suffered shell shock.

The Jeep had set off an anti-tank mine connected to a 250lb RAF bomb which had been buried by the Japs. I staggered back and came across Captain John Day, having closed the road to further traffic.’

Having carried out some deck landing practice ashore at the end of April, they landed on their Ruler and Archer Class Escort Carriers on 29 April. The aircraft were flown off as follows: HMS Khedive (Lieutenant R.J. Hutt), HMS Emperor (Captain ‘Wally’ Boyd), HMS Hunter (Captain John Day), HMS Stalker(Captain ‘Black Mac’ McLinden), on 04 May about fifty miles off Rangoon, escorted by a Supermarine Walrus, with orders to head for the main airfield unless they made contact with their own ground party which had gone ashore in landing craft.

In fact, the members of the landing party were up to their waists in mud on the banks of the delta, south of Rangoon. To further complicate the situation, after releasing them from the carrier, the captain suddenly realized that he did not know whether the airfield was, as yet, safely in Allied hands, but since he had no means of recalling the aircraft there was nothing he could do about it.

As they flew over the city they were among the first to perceive that the enemy had indeed moved out when they saw, on the roof of the gaol, the famous message written by the prisoners-of-war, ‘Japs gone extract digit.’ Inevitably, the pilots failed to make contact with the ground party, finally landing at Mingladon airfield and entering the city from the north in rickshaws, while the assaulting troops were still making their way up the river from the sea.

The inordinate demands being made of the Austers, their pilots and the ground crews were recognized in a letter from the Air C-in-C, Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park, in April, which stated that, as they had been exceeding maximum effort for several months and that there was no possibility of reinforcement until August at the earliest, with spares also being in short supply, present resources had to be used as sparingly as possible in order to eke them out.

Return to Top

VE Day

Victory in Europe, VE-Day, was proclaimed by Winston Churchill and the new US President, Harry S. Truman, on 08 May. A Flight listened to the announcement on Frank McMath’s radio with a slightly jaundiced air,

‘We heard on the wireless that Germany had surrendered, and that the long-awaited Victory Day would be celebrated in England next day with a holiday and merrymaking. Nothing could have seemed more remote from the actuality of our own war. Hemmed in for months past by the jungle, with the enemy on all sides, we had never been able to rouse more than a technical interest in the other war, and now that it had finished we felt a little more than the anticipation of reinforcements and equipment for our next and harder battles towards the “Land of the Rising Sun”.

On the evening of VE-Day the whole Flight gathered round our one wireless set to listen to the broadcasts from London streets, which were relayed from Delhi. Relief and triumph, and gaiety could be read into every word of the programme, but we, crouched in darkness in a crude dug-out lest a flicker of light should bring a shell whining across the river, felt no response to the mood of our country.

We had never known Flying Bombs and V2s and the devastation which they wrought, so we could only realize, selfishly, that the “Forgotten Army” that night was banished from English minds in their joyous celebrations. It was better not to listen for fear of growing envious, so I switched the set off and we all turned our minds back to the problem of the moment.’

Following a very gracious thank-you and farewell from Brigadier Steevens, A Flight arrived at Mingladon on 13 May, SHQ followed on 19 May, with B Flight not far behind. SHQ and Denis Coyle had ‘tackled prodigious feats of organization’ to keep the Flights fully operational and in fighting trim. It had moved with the most advanced elements of 14th Army HQ, with whom it had to keep in touch to obtain supplies, remain up to date about the Army Commander’s future intentions and to receive orders from the BRA, under whose command the Squadron was operating.

Moves were as infrequent as possible to allow the workshop and equipment sections to get on with their jobs. In the advance from Imphal, SHQ had established itself in turn at Palel, Kalemyo, Monywa, Meiktela and, finally, Rangoon.

The war was not yet over, the Japanese forces in Burma had not given up and they regrouped for several months of ultimately futile, but nonetheless fierce resistance. 4 Corps and 33 Corps were now incorporated in the newly created 12th Army, while 14th Army was reconstituted back in India for the planned invasion and liberation of Malaya and Singapore.

It was not until August, after the final significant battle at Sittang in July, that the formal surrender was concluded. Yet, within three weeks of its arrival in Rangoon, the Squadron was once more on the sea on its way back to Madras to get ready for the invasion of Malaya. However, they made their mark in Rangoon by unpacking their dance band instruments and throwing the first dance to be held after the release of the city from the Japanese. Denis Coyle wrote in the Squadron diary,

‘This marks the close of the Squadron’s second operational season and the unit can justly be proud of the results achieved. That no less than 5,708.30 operational hours have been flown since the Squadron resumed operations at the end of September 1944 is in itself an achievement, especially in view of the extensive troubles experienced with the Lycoming engine.

For prolonged periods the Squadron operated at above maximum scale of effort and this, at a period when Flights moved frequently, in close touch with the Army formations for which they worked, reflects great credit on pilots and ground personnel alike. The season’s work has, however, imposed great strain on aircraft and personnel, and renewal of the former and a proper period of rest for the latter is essential before further operations can be undertaken.’

‘C’ Flight ground crew pose with a Japanese trophy on the Royal Lake, Rangoon, Burma, May 1945.

OC’s Summary of Squadron’s Successes

Frank McMath calculated the total number of sorties flown during the Burma Campaign as 6,712, from more than 200 airstrips, most of which were less than 400 yards long, with only four accidents on take-off or landing. Many years later Ted Maslen-Jones wrote,

‘Up to July 1945, 656 Squadron had been awarded two MCs, nine DFCs, two MBEs and many Mentions in Dispatches. There is no record of an award being recommended for any of the ORs and it therefore should be recorded that the list of awards made to pilots was due entirely to the skill and dedication of the ground crew – airmen and soldiers alike. Their performance in keeping the aircraft flying and communications open in such difficult and hazardous conditions, was quite exceptional over such a sustained period.

Of the nine DFCs awarded, five had originally been recommended as MCs. These were changed to DFCs after a directive from London to HQ South-East Asia. However, as both Jarrett and Maslen-Jones had already received immediate awards of the Military Cross in the field, these were not changed.’