Falkland Islands 1982

Kenya Training Falklands Preparation

The Voyage South Operations Begin

The Loss of XX377 Return to the UK

Preface

Below is the story of the last time 656 Squadron was deployed on its own as part of a battle group similar to to previous actions in Burma etc. Army aviation has changed dramatically since those days with the the Apache and the new Wildcat. The Squadron, while at Farnborough, rarely managed to operate as a complete unit at any given time. Pilots and aircraft were either training or supporting other units in diverse operations throughout the world. However, it is because of this that it was able to operate so effectively in the Falklands Campaign.

Kenya Training

While half of the Scout Flight was in Kenya over the winter of 1981, the rest of the Squadron concentrated on night flying. Day was turned into night once a week and all turned up for work at 1800 hours and flew sorties until dawn, then went home to sleep. This training would prove to be of great benefit as events unfolded some months later. In October 1981, part of Scout Flight, commanded by Captain John Greenhalgh, and including Sergeants Dick Kalinski and Ian Roy, had deployed to Kenya with Lieutenant Colonel ‘H’ Jones and the 2nd Battalion of the Parachute Regiment (2 PARA) to conduct infantry training. John flew ‘H’ Jones on many occasions including solo to Masai Mara and around Mount Kenya to Kathendini,

‘Some of the sorties were so far that I was unable to take a crewman due to the altitude and high fuel load/all-up weight required. So he used to sit in the front and help with the map-reading or catch up on his sleep. The role of the CO in Kenya was very demanding … socially.’

John returned to the UK to fly the Scout, along with WO2 Mick Sharp and Sergeant Rich Walker, in the filming of the Pinewood Studios feature film Who Dares Wins, starring Lewis Collins, while Kalinski, Roy and Captain Iain Mackie spent a further few months in Kenya. Iain Mackie recalled that

‘Another unit we were supporting was commanded by Major Cedric Delves (later to win fame for the raid on Pebble Island in the Falklands War), which was based at a place called Impala Farm, a run-down establishment in the middle of nowhere about twenty miles north-west of Nanyuki. A lot involved taking people from A to B, sometimes delivering supplies or mail, frequently flying over a training area to ensure there were no lions or other dangerous animals, and sometimes there were!

Occasionally we were asked to fly with an underslung load, normally some rations or ammunition which was too bulky to carry inside the aircraft, so had to be flown in a net underneath.’

A particular passenger was appreciative,

‘We were advised by the High Commission in Nairobi that Lord Carrington, the Foreign Secretary, was visiting Kenya, and we were requested to support his visit and fly him on a number of occasions round various locations at the base of Mount Kenya to visit some projects that the UK Government has sponsored. I found him to be a very pleasant person, very easy to talk to and a delight to be with.’

Within a few months Lord Carrington would, of course, be in the public eye, as events in the South Atlantic unfolded. In an act which was both unusual and honourable, he resigned as Foreign Secretary on 05 April 1982, taking responsibility for failures within his department to foresee or prevent the Argentine invasion. Back in Kenya, Iain did not enjoy the HALO training anything like as much,

‘The HALO troop definitely made an impact, literally. Nanyuki sits at about 6000 feet above sea level. It is also very hot and the air is much thinner than at ground level. I would take the doors off the Scout, and take the rear seat out. Four parachutists would then sit in the back, with their legs out the sides, feet on the skids. I would then fly up to around 10,000 feet to drop them off.

The temperature up there is considerably colder than at ground level. Going up and down all day from boiling hot to very chilly, back to boiling hot etc – my mother would have warned me about getting a cold! We used to race the parachutists down. They would freefall from 10,000 feet to about 2000-1500 feet above ground level which didn’t seem to take much time at all. But then of course their descent slowed down when they deployed their canopy. As soon as they had left the aircraft, and it had stopped rocking violently, I was able to perform a fast descent, and was normally able to catch them up and land near the drop zone at pretty much the same time as they did.’

Scout Flight was away on exercise in Schleswig Holstein in late March 1982, while the main focus was the forthcoming logistical challenge presented by the move of the Squadron from Farnborough to the equally historic airfield of Netheravon in Wiltshire, which could trace its association with military flying back to 1913. The Farewell Parade had been held on 12 March. Johnny Moss remembers the occasion well,

‘The salute was taken by the Managing Director of the Royal Aircraft Establishment and a flypast of six Scouts and six Gazelles was staged. The guests were seated in front of the Squadron hangar, which was bedecked in Army Air Corps blue flowers. It was a very sad day for all of us as we had enjoyed true independence there. There were no spot visits by Brigade HQ staff, as they had to obtain prior permission and special passes to visit the airfield.’

Falkland Islands Preparation

However, the Squadron was not to know that events many thousands of miles away would have a much greater effect on their immediate future. On the island of South Georgia, 800 miles to the east of the Falkland Islands, the seeds of a conflict were brewing that would ultimately cost nearly 1000 British and Argentinian lives. A party of ‘scrap-metal workers’, accompanied by a force of marines had been landed on the British island and had hoisted the flag of Argentina at the abandoned whaling station. On 31 March, John Greenhalgh flew back to the UK and was as surprised as the rest of the country when, on 02 April, Argentine forces invaded and captured the Falkland Islands. It was the Officers’ Mess Dinner Night at Netheravon and 656 Squadron was being welcomed to its new home by the officers of 7 Regiment. Naturally there was a great deal of discussion and speculation regarding what would happen and what could be done. They were not impressed when at 2200 hours they found out that Captain Chris Hogan’s utility Scout Flight from 658 Squadron had been placed on immediate notice to deploy to the Falklands. By Monday morning, as the first elements of the Royal Naval task force put to sea from Portsmouth, the position had changed. Johnny Moss had been lobbying hard at HQ AAC UKLF that it would be far more appropriate for the anti-tank Scouts of 656 Squadron to deploy. They had the right equipment, SS.11 missile fits and trained air gunners. Also, Lieutenant Colonel ‘H’ Jones had called Johnny to specifically ask for the same Scout detachment he had trained with that winter in Kenya. The deal was done and the Flight Commanders were summoned to Johnny’s office to be briefed. John Greenhalgh describes the scene at Netheravon,

‘We underwent a massive reorganization. Firstly, most of our equipment was piled high in the hangar where it had been dropped by the RCT during our absence in Germany. The G1098 stores [ie. pots and pans, shovels, picks. Every QM or SQMS accounts for these items in his store and is quite often loath to sign them out!] were mixed in with office furniture, REME tools and aircraft role equipment. From this rubbish tip was sifted another pile of equipment that might be suitable for a war in the South Atlantic. Zenith fuel pumps, cargo nets and butane gas cookers were just some of the items.

The Intelligence Section came to give a threat presentation on Argentina. They certainly seemed to have a lot of very good kit, including Chinook, Puma, as well as French and American tanks. The presentation was probably the first time that I realized that we were not up against a bunch of third rate troops and it was all a bit frightening.’

By the end of the week the plan had changed again and the Squadron was placed on seven days’ notice, so John was able to depart on a pre-arranged skiing holiday in Switzerland but, after a few days, Johnny Moss called him back, as the departure of 2 PARA, with Scout Flight as part of 3 Commando Brigade Air Squadron, Royal Marines, was now imminent. While the main focus at this stage was on preparing the Scouts, John also worked closely with Captain Tony Bourne, the Gazelle Flight Commander. Tony remembers that adequate maps were simply not available,

‘Commanders at all levels had to actively seek information. Falkland maps did not materialize, so a last minute rush to the local libraries was made to find and photocopy the most basic of maps – finally copied from a 1960s library book!’

The Scouts were ferried to 70 Aircraft Workshops at Middle Wallop to have radar altimeters (RADALTS) fitted, something that was to prove an excellent decision. John started to assemble and pack his personal kit,

‘I had been told on one brief that the weather was varied. A Falkland summer was similar to UK but a winter was more like Norway. The Falklands was about to end its summer so I packed everything. The planning figure was that we would be away for six months and for me that was a lot of clean clothes.

Finally, I decided to pack it all into a suitcase, kit bag, navigation bag, webbing and a Bergen, which were all full to capacity. This was mainly due to the large selection of hats I took, from my flying helmet to steel helmet, two colours of beret; light and dark blue, a head-over and an arctic cap.’

He was agreeably surprised that when he placed his order for 550 x 45 gallon drums of AVTUR aircraft fuel, the response of the logistician on the other end of the telephone was, ‘no problem, it will be delivered to Southampton,’ instead of the usual request for the copious paperwork and six weeks notice. On Tuesday, 20 April, it was decided that deck landing training would be a good idea so along with Sergeant Dick Kalinski, John flew down to Portland where it was promised that the assault ship, HMS Intrepid, would oblige, ‘Numerous approaches were shot to her from varying directions until QHI Mick Sharp was happy that we had cracked the black art. It seemed too easy, but of course the ship was at anchor!’ Tony Bourne also has vivid memories of the preparations,

‘John and I worked closely together to co-ordinate our efforts. Our initial recces of the large orange English Channel P&O Car Ferries, on which the flights were to travel, were invaluable. We began familiarization of the ships in mid-April in Portland harbour and, with the Senior Naval Officers, determined how best to modify the vessels to become Helicopter Landing Ships in the South Atlantic. These modifications ranged from welding large steel plates to reinforce the decks, concreting up the ships deck-drains, to prevent fuel drainage and spread of fire in the event of a crash, installation of night landing aids and preparation of naval Deck Marshalling Teams and AAC deck handling crews.

The QHI, WO2 Mick Sharp, was invaluable in his tireless efforts of preparing all aircrew for their deck landings and night flights – efforts that were greatly appreciated both before and after deployment. Throughout all of this the REME Section worked tirelessly in integrating aircraft modifications for maritime ops and also preparing themselves for deployment. This included the rapid tailoring of their organization, equipment and spares, to complement the less than precise mission requirements provided by the hierarchy.

WO1 (ASM) Pask was notable in his drive and determination to ensure we were ready for operations in all respects – both in soldiering and aviation fitness. Behind the scenes the newly arrived Squadron 2i/c, Captain Bill Twist, was liaising with the Brigade, for whom he would become Aviation Liaison Officer. He was also to act as the link with the many other units and agencies that required major “prompting” to provide the Squadron with the right kit for deployment, ranging from aircraft IFF transponders to Gazelle SNEB Rockets. The Families Officer, Lieutenant Geoff Clark, was also doing a sterling job of preparing the boys with their Wills and briefing the families on what he knew.’

Back at Netheravon there was some discussion regarding the shipping arrangements – it had been suggested by 2 PARA that the Scouts would travel in the hold of the MV Europic Ferry, a Townsend Thoresen lorry ferry taken up from trade (STUFT) which had limited accommodation, while the personnel would travel from Hull on the MV Norland, a P&O car ferry. Johnny Moss was very unhappy with this and much preferred to have the men travel with the aircraft, keep them on deck, maintain flying skills and potentially provide a useful service. Johnny and John flew down to have a look at the Europic Ferry, which they were told was, ‘a large orange car ferry parked somewhere in Southampton Docks.’ They found it easily and considered landing on the ship but elected instead to land on the dockside between some cranes, which caused a major sand and dirt storm, ‘which did little for Army/Merchant Navy relations.’ Once on board they found the crew were very friendly, including the ship’s captain, Chris Clarke, and there appeared to be no problems putting the aircraft on deck, indeed one of the Second Officers thought that there would be plenty of water to wash down the aircraft on a daily basis, which had been a stumbling block put up to stop the Flight going on deck by Aircraft Branch REME at Middle Wallop. After a couple of phone calls to HQ UK Land Forces the plan was agreed. So the following day three Scouts, XR628, XT637 and XT649, flown by Greenhalgh, Kalinski and Sergeant Rich Walker embarked at thirty minute intervals, to allow time for the ground party to fold the blades and push the aircraft to one side before the arrival of the next helicopter. John returned to Netheravon briefly in a Gazelle to pick up his personal kit and say goodbye to Johnny Moss, to find out that the OC was going to be posted immediately to BAOR to take command of 3 Regiment AAC and that Major Colin Sibun was to take command in his place. Additionally, Captain Iain Mackie, the Squadron 2i/c, was also posted to Germany to be a Lynx Pilot in 1 Regiment at Hildesheim. It seemed a very odd decision indeed to post the OC and the 2i/c just as the Squadron was about to deploy to a potential war zone. The upside was that Iain was replaced by Captain Bill Twist, who would prove to be a tower of strength in the forthcoming months; moreover, Captain Sam Drennan, a very wise and capable aviator, later rejoined the Squadron as a Scout pilot, he had already served as 2i/c and knew the Squadron well. Johnny had been to see the Regimental Colonel at Middle Wallop, Colonel David Canterbury, to plead that he should remain with the Squadron for this operation. After all, he knew the men well, had trained with them and it seemed only logical and right that he should lead them. However, David Canterbury was not sympathetic, quoting ‘the interest of the Service,’ which required that Johnny spend six months writing a report on Future Officer Manning of the AAC before assuming his command in Germany,

‘And in any case, ‘they will only go as far as Ascension Island, get their knees brown and then there will be a diplomatic solution and it will all be over.’

As a result, Johnny spent

‘a miserable two months listening to every news broadcast, wondering how his boys were doing and wishing he was there.’

Johnny Moss left the Army in 1986 to pursue a career in banking but continued flying a Cessna 182, which carries the registration N656JM! Meanwhile, back in 1982, the new OC, Colin Sibun was able to meet and exchange literally a few words with John Greenhalgh before he had to set off for Southampton again in a Gazelle flown by Tony Bourne. Back on board John was somewhat bemused to find that he would be sharing the Bridal Suite with two other officers on the long voyage south – but it did boast two beds and two bunks and a magnificent bathroom with a bath and also looked aft over the flight deck which meant he could keep an eye on flying,

‘The activity on the quayside was frantic. A fleet of RCT Foden lorries was busy unloading 45 gallon drums of AVTUR, which would be stored on the top car (flight) deck, SS.11 missiles, pallets of gun and mortar ammunition piled three deep as well as much more.

The road party arrived with Staff Sergeant Ross REME, who was to be my 2i/c and the AMG team from Middle Wallop arrived led by Sergeant Kanek REME. All our role equipment was loaded onto the car deck through the stern. Airtrooper Beets and Airtrooper Coleman arrived with Lance Corporal Angus in the Land Rover, which was at my request put on the top deck with the aircraft.’

The Voyage South

The Europic Ferry sailed on a fine morning at around 0700 hours on 22 April, ‘no great send off, just a few relatives and one lonely Union Jack.’ In the first instance it was a short leg to Portland naval base in Dorset. They passed the time by clearing the top lorry deck in order to turn it into a pristine flight deck, larger items of rubbish were thrown overboard, with the Chief Officer’s blessing. John also did a private tour of inspection,

‘Around the lower lorry deck to see for myself the vast amounts of stores and equipment we were carrying. The main items were Royal Engineer wheeled plant, 2 PARA’s MT vehicles, my aircraft spares and role equipment and hundreds of pallets of ammunition, mostly gun and mortar but did include some grenades and small arms. There were also two 20 foot containers with locks on. I discovered later from the Purser that one contained potatoes, milk and bread while the other contained a very large supply of Kestrel Lager.’

The Navy’s workup procedure at Portland included drills for action stations, abandon ship, fire practice, damage stations and hands to flying stations. John was issued with ‘a massive pile of Royal Navy aviation publications’ to read, digest and then pass on to the others. On 24 April, immediately after dawn, the ship sailed out of Portland, while the other RN ships all hooted in turn to bid the Europic Ferry farewell and bon voyage. The plan was to sail in company with the Cunard container ship, the Atlantic Conveyor and Norland to Ascension Island. As they were crossing the Bay of Biscay, John spoke with the Europic Ferry’s Senior Naval Officer (SNO), Lieutenant Commander Charles Roe, about doing some flying at sea with a moving ship, before the weather started to deteriorate. He found that Roe, who had no experience of naval aviation, let alone Army Aviation, was very much against the idea. After ‘a series of rather difficult conversations’ with the SNO, John approached Captain Chris Clarke, who gave his approval, so the SNO had to concede and allow the Army to fly at sea. John arranged a flying brief for all concerned, which seemed to consist of most of the crew. Then the ship’s tannoy piped, ‘hands to flying stations, hands to flying stations, no unauthorized movement aft onto the flight deck, no ditching of gash, hands to flying stations.’ John flew for over half an hour doing ship approaches and landings; everyone enjoyed it and was surprised how easy it was and this included the SNO. Flying continued and much use was made of the time available to keep in practice,

‘The weather was beginning to get much warmer and the ship took on a more holiday atmosphere. The pre-flying brief went well, coordinating the expressions which were to be used to attempt a ship controlled radar pick up and recovery with Clive Arnold the ship’s radio officer. The planned training was to include high hovers, max rate climbs to 8000 feet and radar circuits. Unfortunately, the ship’s radar would only pick up 10,000 ton ships and not a small Scout and so ship circuits were abandoned permanently.

We tried a novel form of dead reckoning at sea with a moving base to work from. Using the Dalton hand computer we devised what we thought was a foolproof method of departing over the horizon and then returning on a different heading to accurately intercept the ship. It was really a failure even though it did get you roughly back into the parish, it could not take account of the ship altering course, which the Europic Ferry seemed to do regularly without informing those who were airborne at the time.

In fact it was lucky that the weather was so good with unrestricted visibility, because if you lost the ship all you had to do was to climb until you could see her.’

The next activity attempted was VERTREP at sea (Vertical Replenishment or underslung loads). The session aimed to launch in turn all three Scouts, something which had not been done until then. Once all the Scouts were in the air they approached in turn to pick up a full barrel of AVTUR in a net and then flew away with it. Next came SOATAX (Senior Officer Air Taxi) for the SNO, who wished to pay a liaison visit to the Atlantic Conveyor and who was thereafter ever grateful.

Transportation of fuel barrels between ships is good underslung training.

Transportation of fuel barrels between ships is good underslung training.

John flew the sortie as he had not landed away before and thought the idea of lunch on a different ship was irresistible. He had lunch with Captain Ian North and afterwards had a conducted tour of the ship’s hold, which he found had much in common with Aladdin’s cave, ‘Cluster bombs for Harrier, tents for 10,000, loo rolls for six months, G1098 by the ton and lots more.’ The next ‘hands to flying stations’ was a little hair-raising as John described,

‘The aim was to take some of the 2 PARA personnel on sea/air experience flights. All three Scouts flew and I ended up on the Atlantic Conveyor again, to pick up some kit after the other two had landed back on Europic Ferry. The weather deteriorated quickly whilst I was closed down on the Atlantic Conveyor. On take-off the Conveyor gave me a heading to steer for the Europic as she was not visible through the murk. Having flown for four minutes I lost sight of the Conveyor and I still couldn’t see the Europic. I turned back towards the Conveyor and asked her to check the heading. She issued an apology and then gave a new heading.

Low on fuel I set off again, lost the Conveyor and still couldn’t see the Europic. I was getting alarmed when I spotted the Europic about 40 degrees to the right at about three miles. I made a speedy dash towards her, landed on and thanked my lucky stars. Why I didn’t go back onto the Conveyor for fuel and wait for the weather to clear, or ask the two ships to close, will always baffle me – too proud and stupid to, I expect.’

The only interesting happenings of note during the first week of May were, a brief stop for replenishment at Freetown in Sierra Leone, spotting a Soviet reconnaissance Tupolev TU-20 Bear flying high overhead and a new ship added to the log book, when John flew to the Norlandfor a 2 PARA brief, where, as a bonus, ‘the Quartermaster was giving away all sorts of nice warm clothing.’ Just after dawn on 07 May they arrived at Ascension Island, where the air was very busy with RN and RM helicopters swapping loads between the ships themselves as well as the shore in preparation for the coming assault. John added,

‘To me Ascension Island just looked like a very hot and rocky island in the middle of nowhere, which was just what it was! I was picked up in a Scout and flown over to the Norland for a brief with the Commando Brigade Air Squadron – CBAS Ops Officer. Here I picked up a few more gems on aviation in the Commando Brigade and it was agreed that we would be 5 Flight within the Squadron and would take on that number and call sign.

The aircraft were renumbered from A, C and F to DN, DQ and DV for Greenhalgh, Kalinski and Walker respectively. At 2130Z on 07 May we set sail south in company with Norland, Atlantic Conveyor, RFA Stromness and HMS Fearless.’

Henceforth, flying was restricted to a thrice daily helicopter delivery service between the ships in the group and some night flying training, including ship-controlled approaches, which enabled the three pilots to become deck qualified in day or night operations. On 10 May, John flew ‘H’ Jones from the Norland to Fearless while underway at sea for a meeting. The deck was full and the Flight Deck Officer gave him the wave off, but he managed to sneak on between two Sea Kings and get half a skid on the deck allowing Jones to embark on Fearless. As he remembers it, the Flight Deck Officer was furious but he was more in fear of not getting Colonel Jones onto Fearless for his meeting. As a precautionary measure against salt water corrosion the Scouts were flown to the MV Elk on 11 May, to be stored below deck for six days. XR627 was taken on charge temporarily from 3 CBAS, which enabled sight familiarization flights to the P&O liner Canberra and also Stromness. The Scouts returned to the Europic Ferry and as they approached the boundary of the Total Exclusion Zone (TEZ) around the Falkland Islands on 19 May, each helicopter test fired a SS.11 missile. Sergeant Rich Walker recalled taking the Europic Ferry’s master for a flight over his orange and white ship in a successful attempt to persuade him that the crew should make an effort to tone down the colour scheme before closing with the Falklands. Meanwhile, back in the UK, the rest of the Squadron – three more Scouts and six Gazelles – had embarked in the MVs Baltic Ferry and Nordic Ferry respectively at Southampton Docks, departing in the early hours of 09 May. Major Colin Sibun, SHQ and the Main Party joined ship on 12 May and sailed in the liner Queen Elizabeth 2 along with most of 5 Infantry Brigade. Gazelle Flight, with the assistance of the Master of the Nordic Ferry, Captain Roger Jenkins and the SNO, Lieutenant Commander Martin Thorburn, was able to maintain flying currency on the voyage, again as recalled by Tony Bourne,

‘Daily routine consisted of early morning PT, under the enthusiastic drive of WO1 Pask, then mixes of individual weapon, map and first aid training, AOP and FAC refreshers, followed by deck flying ops both day and night. Deck operations were not at all easy and had significant risks; the fixed-skid undercarriage on Gazelle and lack of negative blade pitch (as with Wasp naval helicopters) made it essential to have slick and disciplined crews on deck. It was a challenge to man handle the aircraft from below decks, up car ramps, and fit blades on deck, all in rough seas. The REME were exemplary in their positive attitude to finding solutions and supporting the flying effort.

The night flying was demanding and not easy with the ship navigating without lights and liable to change course at any time (submarine evasion tactics, we were told!). We almost lost an aircraft, but for disciplined double-checks that had been put in place. We were working in a blackout of communications and lights and, whilst life aboard was generally OK, it did not escape our attention that we were extremely vulnerable. Imagination could at times be potentially dangerous to the team effort and this had to be kept in check.

As we headed south we studied copies of our library book maps of the Falkland Islands – our Ordnance Survey maps never did arrive! Neither did our promised comprehensive instructions for the SNEB rockets that had just been purchased as an Urgent Operational Requirement. We were promised instructions and instructors on arrival on Ascension Island, but as we never stopped there, we never got them. So initiative took hold. REME fitted the rocket systems to the aircraft and Captains Bourne and Piper, with their Royal Artillery rusty and limited ordnance training “inspected” the rockets.

A rare signal was received from HQ Aviation (UK) with a half-page “Chinese Cracker” instruction on how to arm and fire – we now had confidence that we could put our act together. The rockets were never used in action but played an important role in boosting our confidence in the knowledge that we had weapons that could be used as suppressive fire, both for selfdefence and in support of ground troops.’

The QE2 and the two ferries called in at Freetown on 16 May, and then sailed on to Ascension, which was bypassed. One of the officers on board was Tony McMahon, who had served with the Squadron only a few years before and was now part of the Task Force as SO2 Light Helicopters on Major General Jeremy Moore’s staff. He recalls the voyage with pleasure,

‘I joined the bulk of the Squadron on the QE2 just off Ascension Island in early May and had a jolly pleasant cruise south, dining with the Squadron officers when released from my HQ planning tasks. Colin Sibun looked as though he had been in command for months and he was well supported by Bill Twist and Sam Drennan amongst others.

The QE2 was diverted to South Georgia before 25 May, lest she become a prestigious target for the Argentine Air Force on their national day. This was frustrating for all of us, especially Jeremy Moore, as we all knew that D-Day was likely to be before then.’

Life on board the Nordic Ferry was a little less luxurious, as Tony Bourne describes,

‘The Southern Atlantic was cold, bleak and rough! The ferry, designed for Channel waters, almost broke its back. Heavily loaded and with sea states that it was not designed for, it was down to the valiant efforts of the Chief Engineer to literally weld up the broken ship’s hull to keep us going – a remarkable feat of engineering and determination.’

Operations Begin

Meanwhile, the Squadron’s advance element was going to war. Just before dawn on 21 May the Europic Ferry made its way into Falkland Sound between East and West Falkland, then proceeded into San Carlos Water. The first two members of the Squadron airborne that day were Greenhalgh and Walker who ferried supplies ashore for 2 PARA and carried out armed reconnaissance. Dick Kalinski was soon in action too and by the end of that first day each had flown some eight hours, including recovering forty SAS troopers to HMS Intrepid from Goose Green, where they had been conducting diversionary attacks. John Greenhalgh summed up that first day of operations,

‘I watched in horror the devastation of the Leander Class frigate HMS Argonaut as it grappled with its bombs and fire. My first casevac was a para with heat exhaustion – which was amazing because it was cold (he had put on too many clothes) – and I put him onto Norland. While working up and down the mountain, we initially stopped for air attacks, but it was slowing down our work for no result, so we just continued and observed the McDonnell Douglas A-4 Skyhawks and Dassault Mirage IIIs flying past.

On one occasion we were flying down the mountain when we were selected by a Mirage who looked, by his direction and turn, as if he was going to attack us with guns. We followed the drill, which was to accelerate towards the ground, turning to the inside of his turn causing him to tighten further, spoiling his weapons solution. It worked, because he crossed over us with about a 100 foot separation and I could see the pilot so clearly that I almost thought he was going to wave!’

Due to the threat of heavy air raids, the next few days were spent at sea until Europic returned to San Carlos on 26 May. The Flight moved ashore to a temporary Forward Operating Base (FOB) at the foot of the Sussex Mountains near Head of the Bay House. The only unfortunate incident that day was when Staff Sergeant Ross was rendered temporarily insensible, but not by enemy action,

‘I was flying solo and elected to jump out with the rotors turning (frictions on) to help remove the SS.11 missile booms and unload the cabin. I removed the top pin while Ross removed the bottom pin. As I got mine out first, the boom rotated and hit him on the head. Even though he was wearing his helmet, he was knocked temporarily unconscious. Picture us by ourselves, him unconscious yet the helicopter was still running with its anti-tank boom half off! Fortunately he came round and was fine, except he was quite mad at me!’

The excitement continued throughout the following day,

‘Air attacks on Ajax Bay were coming in at dawn and always from one of two possible directions. Before first light we ferried four Shorts Blowpipe teams out into a saddle where enemy fast air had ingressed before, in order to lay an ambush. Inevitably they didn’t come that morning. I flew Brigadier Julian Thompson [CO 3 Commando Brigade] from San Carlos to Port San Carlos by the most direct route over the hill. He bollocked me as he said Argentine SF might try to shoot us down!’

The breakout from the beachhead was about to commence, with 2 PARA as its spearhead. By 27 May the QE2, with Colin Sibun on board, was off South Georgia, and he prepared to cross deck to HMS Antrimas part of the Brigade Reconnaissance Group. The transfer was made by ship’s lifeboat in very choppy seas to the County Class destroyer, which already carried the scars of battle in the form of large wooden pegs hammered into the side of the ship to plug holes inflicted by enemy cannon fire and one very large one where a 1000lb bomb had entered and lodged under the ship’s magazine for twelve hours before being removed unexploded. He would go on ahead while the remainder of the Squadron’s personnel, under the 2i/c (Captain Bill Twist) also transferred to the Canberra. Tim Lynch did not enjoy this part of the proceedings,

‘We made our RV with the Canberra at Grytviken on South Georgia. One day, we found the ship inching its way into the bay past huge slabs of pack ice and began preparations to cross deck. This was an interesting experience to say the least. Fully laden with personal kit and weapon, you stood in a doorway in the side of the ship and waited for the sea swell to lift a trawler up to a level when you could jump across. Mistiming the jump wasn’t really an option.

We then transferred to the Canberra for the rest of the trip. Having come from a life of luxury aboard QE2, Canberra was a very different ship and the atmosphere more businesslike. As we arrived, survivors of ships hit earlier were passing the other way. It was clear by now that we were definitely invited to the party and not, as many had thought, simply intended to act as a garrison after everything settled down.’

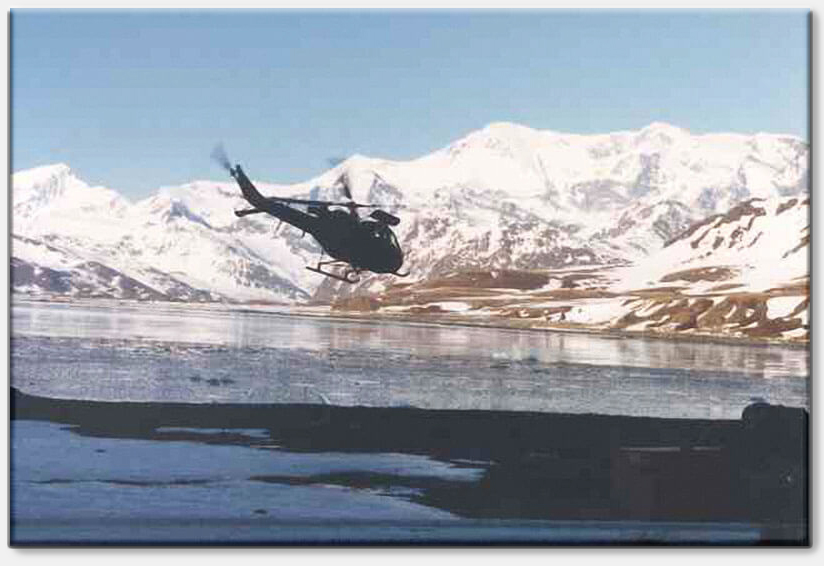

Scout En-Route to South Georgia

On 28 May, John Greenhalgh and Lance Corporal John Gammon, and Sergeant Walker and Corporal ‘Jonno’ Johns were sent to fly casevac missions arising from 2 PARA’s assault at Goose Green and Darwin. John provides an evocative and graphic description,

‘The approach was over open terrain, no cover, past the smoking remains of Dick Nunn’s Scout towards Darwin Ridge [XT629 had been shot down a mile from Camilla Creek House by a Pucara, with the loss of its pilot Lieutenant R.J. Nunn RM and severe injuries to the crewman Sergeant A.C. Belcher RM]. The gorse was all on fire and smoking which helped the navigation somewhat – there was no doubt where the fighting was taking place.

We started a series of evacuations of wounded paras from a number of different finger valleys back to the Red and Green Life Machine [Field Hospital] at Ajax Bay. It was impressed upon me by 2 PARA that they needed more 7.62 link ammunition urgently, so having dropped my casualties at the refrigeration plant, I landed inside the ammo compound at Ajax Bay and sent John Gammon to get the ammo.

He was back empty handed, quite quickly, saying that without written authority we couldn’t have any ammo! I called for the ammo Warrant Officer who, after being pulled into the Scout through my sliding window for an “interview without coffee,” agreed we could have some ammunition – after all there was a war on!’

On 29 May, Colin Sibun transferred from HMS Antrim to HMS Fearless, ‘Another link in the chain of steady deterioration from the QE2 to a hole in the ground’; while back at the FOB, John Greenhalgh stirred his troops into action, having been aroused from deep slumber at three o’clock in the morning in order to pick up a severely injured para, Captain Young,

‘Outside the command post it was very dark and icy cold and I worked my way down a line of frozen sleeping bags waking up half the flight in order to locate Gammon and Walker. I jumped into the aircraft, but the windscreen was just like your car window on an icy morning but with no de-icer spray – I needed to get the engine working to remove the ice. The other two arrived and we departed with Walker and Gammon on the maps hot planning on the move.’

Captain John Young, having being hit by a mortar round at Goose Green, had been lost on the battlefield for ten hours. The return journey with the casualty was frightening, as they entered thick cloud at 200 feet just as they approached the Sussex Mountains. John initiated an emergency instrument climb to avoid the mountains, but as the aircraft was wet it immediately started to freeze and ice over as they climbed through the cloud, holding their heading while Gammon (from the rear) called out the radar altimeter reading. Despite the rate of climb the radar altimeter only registered 40-50 feet. Once over the mountain, they turned through 180 degrees back to the south and flew level on instruments as they watched for the top of the mountain on the radar altimeter. Once it passed they started a rapid descent as the aircraft was vibrating due to the build up of ice on the blades. When they broke cloud they turned north again and descended to ground level using the white landing light. They then proceeded to hover taxi across the mountain top, through the cloud but keeping contact with the ground using the light. When they broke cloud on the north side of the mountain the low-level fuel lights were on and, as John recalls, ‘frankly I hadn’t a clue where we were or which way to go to get to Ajax Bay.’ He called the OC of 3 CBAS, Major Peter Cameron RM, on the radio and explained their desperate plight,

‘He was outstanding; he called all the other radio stations and told them to listen for me and amazingly one of the remote flights told me we were to their south and from there we were able to steer to the Red and Green Life Machine. On the final approach we had a very close call with the sea, by nearly landing in it, as we approached Ajax Bay due to a combination of disorientation, relief at locating the hospital and sheer fatigue – Rich Walker saved the day by pulling hard on the collective after he saw the water out of his side window – what a team effort.

We landed with only fumes in the fuel tank. I elected to stay until first light, have a barrel of fuel pumped into the aircraft and then fly back to the flight for breakfast! In all the casevac took sixty minutes of intense night flying but to me it seemed like just five minutes!’

John Greenhalgh was later awarded the DFC for his actions; in total he recovered fiftyfive casualties altogether in the war. The rest of the day was spent moving other casualties, both British and Argentinian and flying Julian Thompson into the centre of Goose Green immediately after the surrender. The next morning Fearlesssailed into San Carlos Water, Colin Sibun came ashore by landing craft and went to meet the command team of 3 CBAS and also John Greenhalgh, learning that, ‘he had done extremely well and that 2 PARA think highly of him.’ He also recorded his impressions of his first ‘run ashore’ in the Falklands,

‘Recce Squadron HLS. Beautiful day. Beautiful country. Lovely to be back on dry (?) land. Saw Kelp geese, black with sandy-coloured necks and heads, herd of horses, sheep and cows. Meat hanging outside houses to cure. Smell of peat fires. Walk for five hours and kit gets very heavy. Air raid alert on way back to the beach and I leap into RM slit trench. Big bang – controlled explosion of unexploded 1000 lb bomb. Blast damages a Rapier [anti-aircraft missile]. Not very clever. Back on board Fearless for supper.’

Tony McMahon remembers Colin Sibun’s return,

‘Colin came on board HMS Fearless soon after our arrival to discuss tasking etc and he was wet, cold and hungry. Over a hot meal I discovered that the Squadron HLS was totally waterlogged and open to the elements. Radio communications were unreliable due to the poor passage of frequency and codeword information and that, in spite of tremendous efforts by HQ AAC UKLF and HQ DAAvn, 656 Squadron’s aircraft were not fully modified for the task; IFF equipment was non-existent, missiles were not tested and had been difficult to locate.

More worryingly, aviation fuel was in short supply – except on ships – and his aircrew were utilizing captured Argentinian fuel, once checked carefully for booby-traps! Condensation checks on the fuel were impracticable, so the trick had been to fill up and then hover for some moments to see if water had been ingested.’

The urgent task for Colin Sibun was now to reunite the scattered elements of his command. On 01 June the Baltic Ferry arrived with the Scouts, followed by the Canberra and SHQ the next day. The six Scouts were now officially reunited as 656 Squadron at Clam Valley and 5 Flight was no more. The day did not pass without incident for John Greenhalgh,

‘I was tasked to pick up the Land Force Commander, Major General Jeremy Moore from Fearless and take him to Teal Inlet where 3 PARA and the Commandos had yomped to. I was told he would be by himself and as I hadn’t been to Teal Inlet before I elected to take full fuel, which was an error because he turned up with two passengers including his deputy, Brigadier John “Muddy” Waters. There was a 2-star discussion, which I lost, so I decided to take off from Fearlessinto wind and hope that the descent from the side of the ship would be sufficient to compensate for the load! The General might have realized as we departed and descended towards the water that all was not well but God was on our side and the Scout at 102.5% torque climbed away without water impact!’

While Colin Sibun was waiting for the Nordic Ferry to arrive with the Gazelles, the action continued on 02 June. The morning began with searching for Argentine radars on Mount Osborne at first light. In the afternoon, John Greenhalgh, with five Scouts, was tasked to support 2 PARA as it advanced to occupy Swan Inlet House, which was midway between Goose Green and Fitzroy. Two Scouts were missile armed, while three others each carried four paratroopers apiece. Four SS.11s were fired but only one scored a hit, which did not really matter as Swan House was unoccupied. In the afternoon, Greenhalgh and Kalinski, carrying 2 PARA recce troops, cleared and marked the landing site for the Chinook as it flew two missions bringing 156 fully armed troops thirty miles from Goose Green to take control of Fitzroy Ridge. On the way back to base the helicopters had a close encounter,

‘En-route at about 200 feet above ground level and 110 knots, with dusk quickly falling, we were fired upon by infantry – I still don’t know whether it was theirs or ours or SF – but they were lousy marksman because we went directly overhead but they still missed!’

Major Sibun was becoming anxious about the non-arrival of the Nordic Ferry with his Gazelles, so early on 03 June he ‘took a rubber dinghy to go looking for it.’ He found the Nordic but discovered that the Baltic Ferry, having unloaded the helicopters, had sailed out of San Carlos Water with the Squadron’s fuel and stores still on board.

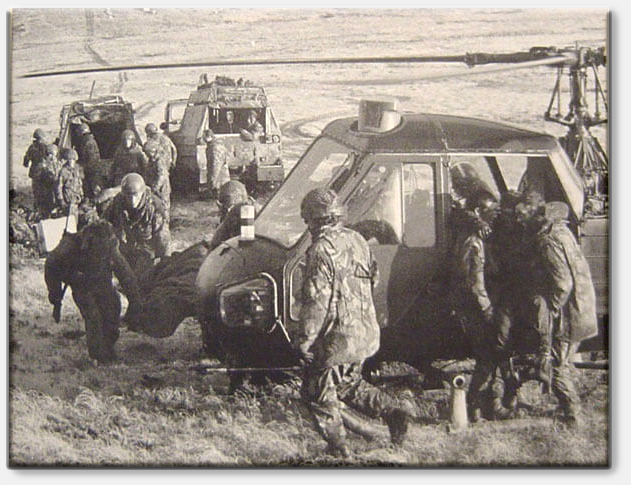

Typical Scout casivac mission

The six Gazelles flew off to Clam Valley in appalling weather and the crews were brought up to speed by John Greenhalgh on local conditions. Gazelle pilot, Captain Philip Piper, remembers a detailed brief given by John in a small dugout, in very poor light with the rain pouring down. He noted in his diary,

‘Everything here (Blue Beach) is an absolute pickle at the moment what with trying to off-load ships and getting 5 Brigade deployed further east. I spent most of the afternoon going from ship-to-shore bringing bods and bits and pieces to wherever they were needed. Last job was to pick up our booms (for the 76 mm missile pods) from about a mile away.

The whole mission was an absolute disaster and I am lucky to be here in my little Gazelle writing this. The strop length was too short for the load and consequently the booms (in the underslung net) began to swing out of control; the load was dropped from about 100 feet. The REME boys are on their way to recover at the moment. (PS – as the ground was so boggy there was no damage incurred by the booms!)’

The OC spent the next day trying to bring some order after ‘the chaotic unloading of the ships which left kit everywhere.’ The highlight of his day was sitting in a very wet and muddy trench eating ‘delicious steak and kidney pie and spaghetti’ cooked by the SSM, WO2 Smith. The possibility of the enemy having sited land-based Exocet missiles was regarded as a potentially very dangerous threat and the search for these occupied John Greenhalgh for much of 05 June,

‘Search for Exocet missiles to the SE of Goose Green including on Lively Island – 300 square miles – which were supposed to be threatening the move of Fearless around to Bluff Cove! Covering huge areas that we had not seen before. At a high state of alert because we didn’t know if we found them, what sort of local defence they would have. Carried SS.11 missiles and a rear machine gunner to do the damage. Nothing found.’

While he was occupied on this wild goose chase both the Scout and Gazelle flights moved to Goose Green, while SHQ and REME’s 70 Aircraft Workshops Detachment remained at Clam Valley. Philip Piper noted on 05 June,‘Spent most of the day transiting between San Carlos and Darwin/Goose Green. Spent an hour looking for an Argentinian radar site – no luck. We moved out of San Carlos into Goose Green settlement which is simply a couple of dozen houses scattered around a jetty. No roads, no shops, nothing apart from a lot of misused or unused military hardware. The airfield, which is only a grass strip, has two u/s Pucara aircraft on it plus two dumps of bombs.

There are still 240 prisoners in the wool shed here in the settlement…We are fortunate enough to have taken over a wee house and although pretty sparse, it’s better than living in a grotty trench. The house has only got two bedrooms and it’s actually sleeping twenty-eight of us tonight – v cosy!’

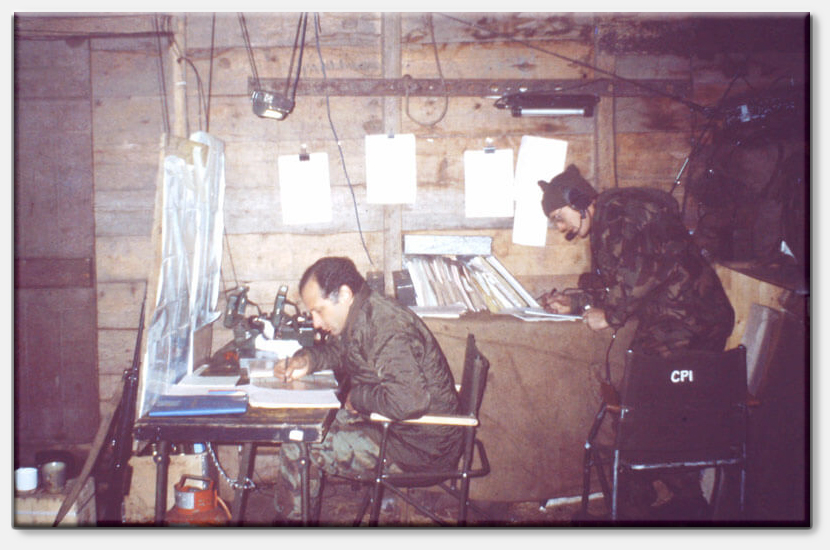

OC Major Colin Sibun and SSgt Dave Ward in Squadron HQ, which was at one stage based in a cow shed at Fitzroy

OC Major Colin Sibun and SSgt Dave Ward in Squadron HQ, which was at one stage based in a cow shed at Fitzroy

It was a really bad day, 06 June, in the early hours of the morning the OC received a report from a Royal Signals rebroadcast station of a loud explosion and two white flashes in the vicinity of Mount Pleasant Peak. Tony Bourne was standing in the open awaiting the return of the helicopter and as he looked out toward the mountains, suddenly saw a starburst flash in the sky above the mountain range, then a second.

Return to Top

The Loss of XX377

Staff Sergeant Chris Griffin and Lance Corporal Simon Cockton had been tasked to fly Gazelle XX377 with Major Mike Forge and Staff Sergeant John Baker, both Royal Signals, as passengers, in order to service a rebro station on the Peak, thereby maintaining a forward communications link between 5 Infantry Brigade and 2 PARA. Chris Griffin was a very capable pilot who had previously served with Colin Sibun in Northern Ireland. It was inconceivable that someone of his skill and experience would have flown into the ground and enemy action was the immediate logical conclusion. There had been no radio contact with the Gazelle and no information other than the report from the rebro station. It had been a clear, cold, moonlit night but was becoming foggy locally and there was also the threat of enemy fire from OPs along the high ground, so the OC decided that he had to wait until first light before initiating a search. He led the search in which four helicopters took part and mid-morning they found the crash site. It was readily apparent that the Gazelle had sustained a direct hit from a missile to the rear fuselage/fenestron tail area and that it would not have been survivable. Tony McMahon was given the task of visiting the site of the crash site to make a preliminary investigation,

‘On arrival at the scene, I was dropped off and the Scout flew off to high ground to over watch my activities with its SS.11. We had no idea where the enemy was at this stage. Sadly, all four were lying where they had crashed and had obviously died instantly.

The aircraft had been lacerated by some kind of shrapnel and bits of it were embedded in the jerrycan carried by the passengers, presumably in case the generator for the rebro radios had run out of fuel. It was quite obviously not aircrew error and that it had been shot down. As we had no idea where the enemy were and that we knew they had air defence weapons I reported that the crew be listed as “lost in action”. This was subsequently challenged and the whole incident clarified in a full enquiry some four years later.’

Tragically, it was a blue-on-blue incident as the missile was later shown to be a Sea Dart fired from the Type 42 destroyer, HMS Cardiff – within the parameters of the existing Rules of Engagement. The subsequent Board of Inquiry recommended that neither negligence nor blame should be attributed to any individual. This was the Squadron’s only loss of life during the conflict; made all the more tragic by the circumstances under which it occurred. Towards the end of the day Colin Sibun briefed all ranks on what had happened, with SHQ now moved forward to Darwin, taking up residency in several barns, unoccupied houses and a greenhouse. Once more John Greenhalgh’s memories bring an intensely human touch to the reality of war,

‘Went to Ajax Bay to collect body bags for Chris Griffin and Simon Cockton and while John Gammon was inside the hospital, RSM

Simpson from 2 PARA climbed into the Scout for a chat about who had been killed and injured during the battle for Goose Green. Picture us sitting in a Scout on the ground at Ajax Bay, with me at the controls and the blades going round and both me and the RSM in tears; it was awful, we agreed it was also just not fair. Gammon returned with the body bags, we sorted ourselves out and got on with our work.’

Colin Sibun’s diary records a much more positive encounter with Argentine forces on the following day,

‘Contact in the afternoon. Two Scouts (Captain Sam Drennan and WO2 Mick Sharp), are deploying Gurkha OPs with an SS.11 Scout (Sergeant Ian Roy) escort. Egg Harbour House is approached tactically and appears clear, but at a range of 200m enemy soldiers come out of the house and run off. Scouts land troops and return to collect more. Sergeant Roy remains on watch and is joined by Captain Philip Piper and Lance Corporal L. Beresford in a Gazelle.

Drennan leads in two 825 NAS Sea King HAS2As with troops. Corporal Johns fires a missile from Roy’s Scout in the general direction of the enemy who come out of hiding. They are surrounded by the helicopters and taken prisoner. A potentially disastrous task has been turned into a very big feather in the Squadron’s cap. Among the weapons captured was a Soviet SA-7 man-portable SAM.’

During the course of this action, Lance Corporal Gammon got out of his helicopter with the Gurkhas and ran forward to take the surrender, but when jumping a fence the top button on his combat trousers broke and they descended to his knees leaving him with his gun in one hand and his trousers in the other – but he still made the capture! Philip Piper wrote on the 07 June,

‘We could actually see the countryside, in comparison to yesterday and it is really outstanding. We’ve been ordered not to fly above 50 feet so one gets a good look at the local wildlife. One of the Scouts had a bird-strike today which is one of the pitfalls of low flying. The islands are well suited to this sort of flying because the only wires around the place are those connecting telephones which fortunately don’t get higher than 10 feet. Spent most of the morning going back and forth to San Carlos with various bods (all flying to date and hereafter with Lance Corporal Beresford, who was brilliant throughout).

Had the opportunity to go up to Fitzroy this afternoon which is closer to where the action is. It’s a little settlement on the east side of the island and a mere twenty miles from Port Stanley. Whilst I was there a Para managed to shoot himself in the stomach with a pistol and as I was involved in another task, Captain Tony Bourne had to take him to Red Beach in Ajax Bay – I believe he is quite comfortable.

Spent an interesting afternoon looking for Argies fifteen miles to the South of Goose Green. The eventual outcome of the incident was the capture of eight of them. Lance Corporal Long did sterling work with getting the prisoners onto the ground and searching them.’

While the Squadron was preparing to move to Fitzroy on 08 June the devastating air attack on the LSLs Sir Tristram and Sir Galahad took place. Some of the attacking Skyhawks gave Dick Kalinski and Lance Corporal Julian Rigg in Scout XR628 a very unpleasant surprise; Kalinski immediately took evasive action by getting down as low as possible, bringing the helicopter to a hover a few feet above McPhee Pond.

On June 8 1982 Sgt Dick Kalinski and his crewman LCpl Julian Rigg had to make an emergency landing

His day did not improve as, when the coast was clear and he engaged power to resume tasking, he suffered a tail rotor driveshaft failure, with the result that the Scout had to make a rapid forced-landing in the shallow freshwater pond. The crew suffered not much more than wet feet, using the cabin door as a raft to reach the shore, but it would be several days before the helicopter could be recovered. John Greenhalgh picked up the crew,

‘I located the rather wet and bedraggled team on the lakeshore and so I closed down to establish what had happened. While I was being briefed, a Skyhawk flew over us very low and it was being followed by another so we cocked our weapons and prepared to fire at the second as it bore down upon us, when one of the aircrewmen, who was more able at aircraft recognition than the pilots shouted “Harrier!!” So we desisted!’

Tony Bourne describes his very close-up view of the action,

‘Landing on Sir Galahad for the second time for a rotors-running re-fuel, Lance Corporal Fraser and I were suddenly overflown by two Skyhawks. It was not a good time to hang around and we rapidly departed the ship expecting an attack on us, and so having landed ashore, shut the rotors and left the engine running, we took cover. We waited expecting the worst, but with nothing seen, we then headed back to the ships. Suddenly we saw palls of smoke – we initially thought that the ammunition dump that the LSLs had been offloading was alight, but alas it was Sir Galahad and Sir Tristram that had both been hit.

As we approached the damage became evident and we realized that there were likely to be many casualties aboard the ships. I broke radio silence, and called the RN Sea Kings that I had seen earlier – fortunately they responded and the rest is well documented. It was a bloody horrific day for the Squadron’s Scouts and Gazelles, spent ferrying casualties back to the Red and Green Life Machine in Ajax Bay.

On one of our many casevac transits we suddenly saw a hospital ship, white with a Red Cross, sitting offshore – it was SS Uganda. With her being closer than Ajax Bay we decided to take casualties directly to her. On landing we were efficiently received, too efficiently, as they stripped me of my personal weapon – my SLR was grabbed and thrown overboard – not welcome, but minor in the scheme of things.

The very long day over, we recovered Lance Corporal Fraser’s pilot seat and our Gazelle doors that we had left on the beach – he had spent most of that day in the back tending to the wounded in transit – applying the saline drips and encouraging the wounded to “hang on in there”, whilst desperately hanging on in the back keeping himself aboard. The nasty job of “swabbing out” the Gazelle then fell to the REME that night – not a nice job. It was such sterling work by the REME and Ground crew.’

Colin Sibun flew forward to Fitzroy to find that SHQ’s new location was a cowshed, with Scout Flight’s office being the garden shed. Tim Lynch adds a touch of the typical Army humour which served to keep up spirits, ‘I rejoined Squadron HQ, it was fully established in a barn shared with cattle. Although the smell was bad, the cattle didn’t complain.’ A defence perimeter had been set up by SSM Smith, with the ground crew and REME Section providing the local defence, sustainment and maintenance that both Flights needed. There were also the dangers of minefields and booby-trapped fuel stocks, but this did not hamper operations. All personnel spent several hours digging trenches against the possibility of further air attacks. Tim Lynch describes the scene at Fitzroy,

‘At this point, 5 Infantry Brigade was setting up its HQ in the lumber shed when an “air red” warning came in. These were regular enough and not taken too seriously by now. I had just brewed a cup of tea and was sitting in a corner with my radio headset on. I glanced over my shoulder and saw everybody had taken cover. I started to move just as the blast hit the shed. It was like the slamming of a huge door and dust began to fall. Covering my tea to stop it getting full of bits, I remember thinking it was just like the old war films. Although I don’t remember doing it, I was told later that I sent out a contact report immediately.

Someone shouted that they were coming again and I ran outside to take cover behind a pile of logs. An officer landed beside me and pulled out his Browning pistol. What he intended to do with that against a Skyhawk I wasn’t sure but as the jets passed, he let off a few rounds anyway. A second strike came in later that day and was met with a wall of small arms fire. I read later that an estimated 17,000 rounds were blasted off at them. Certainly the vast amount of tracer seemed to do the trick and they veered off.’

Another small landing craft had been hit that afternoon, the OC’s driver, Airtrooper Price was injured, while the Squadron Land Rover, War Diary, radios, tents, the OC’s logbook and his entire supply of Mars Bars ended up at the bottom of the sea. The following day Sergeant Ian Roy was delivering supplies to the Scots Guards at Mount Harriet House when their position came under intense mortar fire. After it had ceased he flew two injured Guardsmen to hospital and had a near miss with an Argentine Blowpipe missile. His was not the only lucky escape that day, as Sergeant G.H. Keates and Lance Corporal J.A. Coley very nearly had a catastrophic encounter with a very large, air-portable fuel cell. They had landed a Gazelle on the Harrier strip at Port San Carlos and had commenced refuelling with rotors running. Suddenly Keates noticed the cylindrical fuel cell rolling down the slope towards them. His crewman was standing on the landing skid with the hose, so Keates’ choices were limited. He was able to lift off a few inches and rotate the helicopter gently; just enough to let the fuel cell brush past with only very slight damage. The next day, 10 June, WO2 Sharp and Staff Sergeant Ross also had some interesting times, as described once more by John Greenhalgh,

‘Move our own fuel to Fitzroy – two drums at a time, refuelling only at Goose Green so that the stocks would build at Fitzroy. WO2 Sharp departed in daylight for a short task and returned after dark and was really quite angry! When he walked round the aircraft after he had landed, he found one hundred yards of telephone wire wrapped around the helicopter tail rotor. Almost immediately we received a complaint from the Royal Signals that someone had destroyed their new telephone link, which they had only just put up sixty minutes before – stringing the wire across the gaps between buildings! WO2 Sharp went to speak to them and to give them back their wire!

One of the Scouts wouldn’t start after dark and it was assessed that it needed a new torch igniter. There was of course no spare but Staff Sergeant Ross, my amazing engineering officer said there would be one on Kalinski’s Scout in McPhee Pond. “Let’s go and get it then,” I said, but a lack of tools would have precluded progress until the farmer, who we were living with, lent us a pair of pliers.

We departed in a Scout with Ross in the back with his pliers; locating the Scout in the dark in the lake. I hovered over it, dropping Ross on to the roof. Unfortunately, Kalinski had not applied the rotor brake when he had egressed. Under the downwash of my Scout the blades started to sail round requiring Ross, a proud Scotsman, to jump up and down on the roof every time a blade passed – which was frequent – he cut quite a dash with his Scout Highland fling. I departed to the shore to allow Ross some peace and five minutes later, after the flash of a torch (the prearranged come and get me signal) I picked him up again with the torch igniter – hurrah!’

The Squadron also spent a considerable amount of time in preparation for the forthcoming assault by 3 Commando Brigade on Mount Longdon, Mount Harriet and Two Sisters and also on resupply and maintenance visits to the Rapier missile sites around Fitzroy and Bluff Cove, while Ian Roy was tasked to recover a Scots Guards’ officer from a covert OP point at Port Harriet House on the far side of a minefield. He flew in ‘very tactically’ but was engaged by mortar and small arms fire, which caused him to retreat hastily once he had picked up his passenger. Gazelle Flight was primarily involved in command and liaison duties, flying most of the commanders to their O Groups – to the forward dug-in infantry and artillery positions, and insertion onto high ground of OP, FAC and Rebro parties. Passengers included Major General Jeremy Moore, Brigadier Tony Wilson and the War Artist, Linda Kitson. Tony Bourne’s observations are of interest,

‘Missions to the forward areas by helicopters inevitably attracted direct or indirect enemy fire. Interestingly, with flying helmets worn, combined with the noise of the aircraft engines, the fear factor of artillery and tracer was diminished. Only when one closed down and took off one’s helmet did one realize the seriousness of staying too close and too long.’

Test firing also took place of a Gazelle fitted with SNEB 68mm rocket pods (which in the event were never used). Greenhalgh and Kalinski were attached to B Flight, 3 CBAS for the assault and on 11 June were at Estancia House,

‘Living in the back of the aircraft in even more austere conditions than we were used to!’

Colin Sibun had also become used to unconventional accommodation,

‘Living in a cowshed with several cows is not uncomfortable but is a little cramped. Fresh milk in the morning is a bonus.’

He had also persuaded a naval Sea King pilot by a ‘combination of threats, taunts and the promise of a bottle of champagne’ to uplift XR628 from McPhee Pond and bring it to REME, who removed its engine and fitted it to XT649, which was ailing. Philip Piper was also keeping busy as these extracts from his diary show, ‘10 June. Day started with Staff Sergeant Emery as an advisor for the test firing of the SNEB rockets (we had never fired them before this!). Went ten miles to the east of Goose Green to see how the things worked. It was great fun – the rockets are not particularly accurate (foresight being a chinagraph mark on the Perspex of the canopy) but they would certainly give the enemy a bit of a scare. Have just returned from a pretty harrowing night sortie. The Scots Guards needed some kit badly and decided they needed it tonight, so a Gazelle (me) was tasked to guide the Scouts in. The night was pitch black and it took us three attempts to actually get down. Anyway the sortie was successful so hopefully the Scots Guards are feeling eternally grateful.

11 June. Spent the morning looking after the Rapier battery – they are located all around Fitzroy and Bluff Cove. The gun batteries have been pounding enemy positions in and around Fitzroy and Bluff Cove for the last three days. Spent the rest of the day taking Major Tim Marsh around the various locations. He is the Deputy Quartermaster for the Brigade; the poor chap has really got a job and a half on his hands as half of its stores were on the LSLs that were hit in the Sound.

Managed to pop on board MV Nordic this afternoon. She is still unloading her stores. All the ships officers gave us a very warm welcome when we came aboard. Managed to scrounge some fruit and bread out of the galley and they were kind enough to sell us some beer and whisky.

12 June. Nearly freezing and its freezing literally. Spent two hours yesterday morning sitting in my trench from 0200-0400 waiting for an air raid which never came thankfully. We’ve just had another one – only half an hour this time. It was thought that four enemy aircraft had taken off from Port Stanley and were on their way to us. We heard their engines but fortunately they didn’t drop anything. Must get some sleep – am absolutely knackered.’

Goat Ridge June 12 1982 – Capt Philip Piper and his crewman Cpl Les Berrisford flying a CASEVAC mission

Kalinski had another close shave on 13 June, which was observed by John Greenhalgh,

‘Daylight casevac from 3 PARA Mount Longdon, mostly artillery casualties. Then Kalinski was leading as we flew into 3 Commando Brigade’s HQ pick-up point to drop off some passengers. I was trailing by about half a mile.

To my right I suddenly saw seven Skyhawks approaching low from the west, obviously intending to attack the Brigade HQ, which was further to the east. The first thing they saw was Dick in his Scout, XT637, so they attacked him. Several 1000lb bombs dropped on either side of his aircraft and there were several loud explosions.

The enemy aircraft departed, Kalinski closed down and a quick inspection by Corporal Ian Mousette revealed shrapnel holes all down the side of the Scout’s tail boom, but miraculously no one was hurt.’

Another casualty of the raid was Gazelle ZA728 which had its Perspex bubble canopy shattered. Both aircraft were recovered to the rear echelon at San Carlos for repairs, although the Scout was able to fly immediately after the attack, the Gazelle could not, as it had suffered serious damage to the instrument panel. Shortage of spares meant that it would be some time before they were available again. At one minute before midnight the final offensive of the battle to recover the Falklands began when the Scots Guards and the Paras assaulted Tumbledown and Wireless Ridge respectively. Helicopters from the Squadron were heavily involved in day and night casevac missions over the next twenty four hours. Greenhalgh and Gammon flew many sorties in extreme weather conditions and under enemy fire, while Drennan and Rigg accomplished a particularly difficult mission successfully when evacuating three Scots Guardsmen and a Gurkha from a very exposed and inaccessible position on Tumbledown. Tim Lynch was on Goat Ridge manning a rebro post,

‘From the top I could make out the Argentine hospital ship in Stanley harbour and a few of the houses on the outskirts. I settled down in the rocks and got to work. My abiding memories of that morning are of Captain Sam Drennan and Corporal Jay Rigg flying in and out of Tumbledown with Captain Drennan’s radio stuck on send, allowing me to eavesdrop on his comments as he flew in to what was a very dangerous situation.

After picking up the wounded, he would then scoot around Goat Ridge and fly low along the valley floor just below me. It was humbling to hear the determination with which he kept promising the guardsmen he would come back. Himself an ex-Scots Guardsman, I know that he knew some of the men personally and it was clear he would do everything he could for them. I recall hearing the voice of the Squadron Commander telling him he was under fire – again – in what sounded like an exasperated tone as though he was talking to a wayward kid.’

Sam Drennan was later awarded the DFC for his efforts that night in recovering sixteen wounded soldiers in the most hazardous of circumstances and in the course of seven sorties under enemy fire. His thoughts regarding his very busy night are as follows,

‘There were casualties scattered all over the mountain. At one point the Scots Guards were firing M79 grenades over the top of my Scout at a sniper 50 yards from us on the side of a hill. I don’t know how he could have missed us – probably the grenades landing around were putting him off a bit.’

Colin Sibun and Airtrooper Beets moved up to Tumbledown with a radio to coordinate the casevac tasking. He noted that it was snowing and bleak and that a piper played laments as the dead, wounded and prisoners were brought back by three Scouts amid shelling and sniper fire. John Greenhalgh added some thoughts of his own experiences that night,

‘Then several night casevacs from 2 PARA on Wireless Ridge back to Fitzroy. Hover taxying forward in total darkness, with no lights except for the continuous tracer fire arcing over the top of us from 2 PARA’s GPMG guns in the sustained fire role. Several return journeys in the dark with very poor visibility.

Returning to Wireless Ridge about two hours before dawn with Kalinski leading, it just became impossible so we elected to stop on the mountainside and await first light. We didn’t really know where we were, Scouts didn’t have any navaids, where the enemy was, or anything for that matter. But being British we decided to make a brew and keep our fingers crossed!

As it became grey we lifted and returned to 2 PARA on Wireless Ridge who were still consolidating. So we continued to take ammunition forward to the company positions.’

These activities continued on 14 June as the battle for Tumbledown reached its climax and as the enemy retreated towards Stanley, a Scout crew joined in the offensive along with two 3 CBAS crews, again in the words of John Greenhalgh and [John Gammon],

‘Dawn attack – using SS.11 missiles onto Argentine Pack Howitzer battery, which was dug in just west of the Stanley Race Course. Major Chris Keeble of 2 PARA was frustrated that the Milan anti-tank missile, which had a range of 1950 metres, would not reach across the water to where the Argentine battery was firing at the Scots Guards who had not yet taken Tumbledown. Keeble asked if it could be done but as we were not fitted for missiles we had to return to Estancia House where we were refuelled, fitted with launchers and then missiles without closing the aircraft down – a first for Scout.

We could sense that victory was just around the corner. An O group was held with two Royal Marine Scouts in front of Greenhalgh’s helicopter, which saved extensive radio orders and we departed while the other two Scouts got fitted and ready. I was back with 2 PARA within twenty minutes and conducted a detailed recce and located the target and a suitable firing position and fired two missiles and then returned to the prearranged RV in order to guide in the other two Scouts.

[We aligned into an attack formation, flying in line abreast, with the high ground behind us, so it was quite a reasonable firing position. I spotted three bunkers, talked the others in and allocated targets. I fired one of my missiles and it went into the bunker].

We fired a total of ten missiles at a range of 3000 metres, taking out the guns, bunkers and the command post (one launch failure and nine hits). After the first missile hit, you could see the troops running away from the guns in the direction of Stanley. Unfortunately we had been spotted and we were precisely targeted by enemy mortar fire, rounds landing around the aircraft. 2 PARA, who were digging in around our firing position, were not amused that we were attracting enemy fire.

As Lieutenant Vince Shaugnessy RM departed from the firing position he still had a rogue missile on the rails, which would not leave. He kept diving the aircraft in the hope that the missile would fall off! 2 PARA later said they had thought that he had been hit and that he was fighting to regain control of his Scout.

Then we moved the Mortar Platoon forward to give them better coverage of the 2 PARA area and the deed was done as Brigadier General Menéndez and his troops surrendered at 1630 ZULU! In the afternoon moved back to Fitzroy.’

Philip Piper adds,

‘At about 1100 hours today a white flag was seen to be flying over the capital of the Falklands. I was looking after General Moore today and was the first British aircraft into Stanley. The locals were over the moon on seeing us. We seemed to have spent the rest of day shaking hands.’

And Colin Sibun recalled,

‘Relief swept over us. I then discover that I have walked through a minefield earlier in the day while working myself forward to find suitable casevac positions. I must have lucky boots!’

However, for Sam Drennan it was not yet all over, as he still had a tricky casevac to fly from Sapper Hill, which was completed in such a heavy snowstorm that he needed to be talked-in to land on a “T” marked out by vehicle headlights. He has vivid memories of this flight,

‘We (Mick Sharp and I) landed in a snowstorm in pitch darkness, assisted by the lights of a landing aid and directions on the radio. The weather was so bad that I delayed take-off for a few minutes after the casualty was loaded and Mick remained in the back to comfort the soldier.

The snow cleared sufficiently for a safe take-off and as I transitioned forward over the upwind edge of Sapper Hill we were hit by a violent updraft which was so fierce that it caused the main artificial horizon instrument gyros to topple. This coincided with a severe snowstorm which obscured everything outside the aircraft. I reverted to the standby artificial horizon, which is a small instrument about the size of a pocket watch and headed for the sea to avoid colliding with any high ground.

My main instrument was all over the place and I was suffering from severe disorientation due to the aircraft being thrown about in the turbulence. The voice from the back, as Mick calmly read out the radar altimeter readings, was very comforting as I struggled to overcome disorientation. It was an almighty relief when the main artificial horizon started working again, but we were still stuck over the sea at 200 feet, flying on instruments, in a snowstorm, in the dark. I felt badly in need of a hug at this time!!

Eventually the snow reduced slightly and we found the coast after about fifteen minutes and recovered to base, unscathed but exhausted. Colin took one look at me and promptly grounded me for a day to recover, as apparently I looked a bit rough. Mick was quite outstanding – brave, calm – he contributed greatly to the success of this mission. I had attempted the same mission earlier accompanied by Jay Rigg, in better weather (though there were intermittent snowstorms) but failed due to communication problems with the Welsh Guards and also almost collided with a mountain.

Jay Rigg saved my bacon on that occasion. It was pitch black and snowing when in the nick of time he spotted it looming ahead. I switched the landing light on, saw the mountainside and managed to avoid it.’

Once control of Port Stanley had been established the Squadron moved to the racecourse, where several Argentine Bell UH-1H Hueys were found to be in flyable condition.

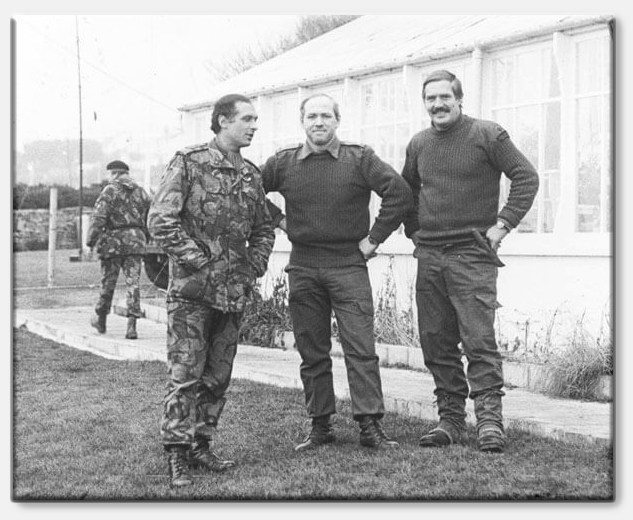

Captured Argentine Huey AE 409 which was renumbered 656 and pressed into service

One of these, AE-409, was pressed into service, with the serial painted out and a large ‘656’ added. OC Colin Sibun and QHI Mick Sharp carried out the initial test flight, as Colin later recalled,

‘I jumped into the right-hand seat, and Mr Sharp got into the left. We had no experience on that type at all, but just “kept everything in the green” as we taught ourselves how to fly it. It flew very poorly at first (the tracking was badly out), but REME soon sorted that out, and it was put to good use from that point onwards.’

Philip Piper’s diary adds some further details,

‘15 June. Again I was looking after the General. Took him to West Falklands in the afternoon which was most interesting. The first port of call was Port Howard. There were over 1000 Argies there having their weapons and ammo being taken from them and then being ushered into a wool shed. Within four days they will find themselves back in Argentina having been taken there on SS Canberra or the MV Norland. The Argies can’t wait.

The second port of call was Fox Bay in which the Argies were even better organized. By the time the RN had arrived there first thing in the morning they had stored all their weapons and were busy clearing the minefields. They numbered about 1000 strong and it did seem a little strange seeing just seven sailors administrating them, and half of the sailors were in the homesteads tucking into tea and shortbread.

I had a hairy trip back to Stanley as the weather had turned really bad with the wind gusting up to 50 mph; the turbulence over the hills was terrible. I was certainly glad to get back to our cowshed (in Fitzroy) this evening.

16 June. Spent the day with the General again; took him to SS Uganda to say a fleeting hello to all the poor casualties. The only one we’ve got is Airtrooper Price who was hit whilst travelling up from Goose Green on an LSL. He had temporary blindness for four days but is now recovering fast. The crew very kindly gave us a stack of eggs, bacon, rolls and butter which really boosted our morale. John Greenhalgh spent the evening with us which was a welcome change. Drank some beer and had a good chit-chat.

17 June. Had my first day off today. The morning was fine but the afternoon dragged. We changed the time back to local, which is three hours behind, so this has been quite a long day. We heard that General Galtieri resigned today which was great news. As yet not all the Argentinians have surrendered to us so we are still on our guard.

A Sea King got shot at today; I don’t think the aircraft was hit but it certainly gave the crew a fright. Am back on flying duties tomorrow which is good news. As yet we have not heard when we are going home – it ranges from three weeks to six months!’